ART

A Talk Between Mel Bochner and Carroll Dunham 50 Years in the Making

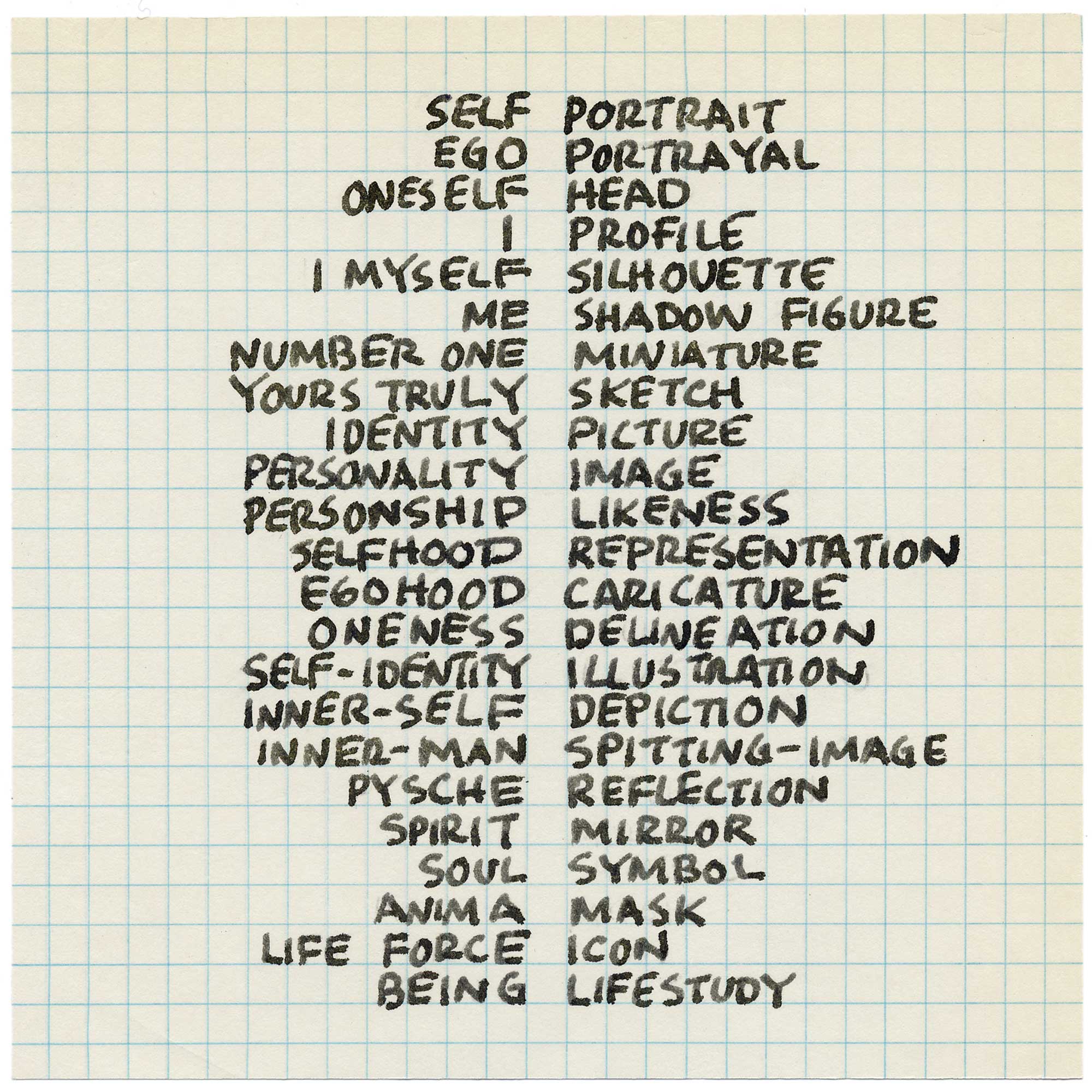

Mel Bochner, unabashed materialist? It just doesn’t sit right. Isn’t he, after all, the impresario of graph paper and measuring systems, of intangible numbers and words, of mutable materials that blow away like so many curse words in the wind? Certainly, that is one well-established side of his radical and critical split with painting-obsessed mid-century modernism. But to look at his work another way, the legendary American conceptual artist was merely paddling toward uncharted waters, expanding the definitions of materiality. In the late 1960s, Bochner had already made the iconic word portraits of his art-world friends such as Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson, and Sol LeWitt (rendering them, thesaurus-like, in a series of single-word descriptions shaped into various artful forms on paper) when he visited an exhibition of Italian frescoes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That 1968 show proved a revelation for Bochner, leading him to eventually pick up a piece of blue carpenter’s chalk and rub it on his own studio wall. The result was a work called “Smudge.”

As with so many conceptual and post-minimal artists of the 1960s and ’70s, Bochner found Europe more receptive to his challenging formulations than the market-driven art-world capital of New York. Galleries and institutions in Italy and Germany proved particularly inviting and fertile. Many of his key elemental works—including his famous uses of stones and chalk in various systematic modes of arrangement, often humbly situated on the gallery floor—were shown in Europe during this decade. It was in Italy that he ran into like-minded artists such as Alighiero Boetti, whose own use of language, counting systems, humor, and unconventional materials would rhyme with Bochner’s enticing experiments. This past winter, Bochner collaborated on a special exhibition of his work in conversation with the arte povera masters Boetti and Lucio Fontana at Magazzino Italian Art in upstate New York. Bochner displayed and restaged a number of his masterpieces, including a stark work from 1993 that is composed of burnt matchsticks arranged in the Star of David on an old U.S. Army blanket. This extraordinary three-way pairing was the latest in a number of recent Bochner reexaminations back in his home state. In 2019, Dia Beacon invited him to reprise one of his iconic “measurement room” pieces, first staged in 1969 at a gallery in Munich. At Dia, Bochner used red tape to systematically measure and grid an enormous gallery, as if to make a room that normally functions as a forgettable white-walled backdrop “real” again. Or perhaps even less real, part of an abstract dimension.

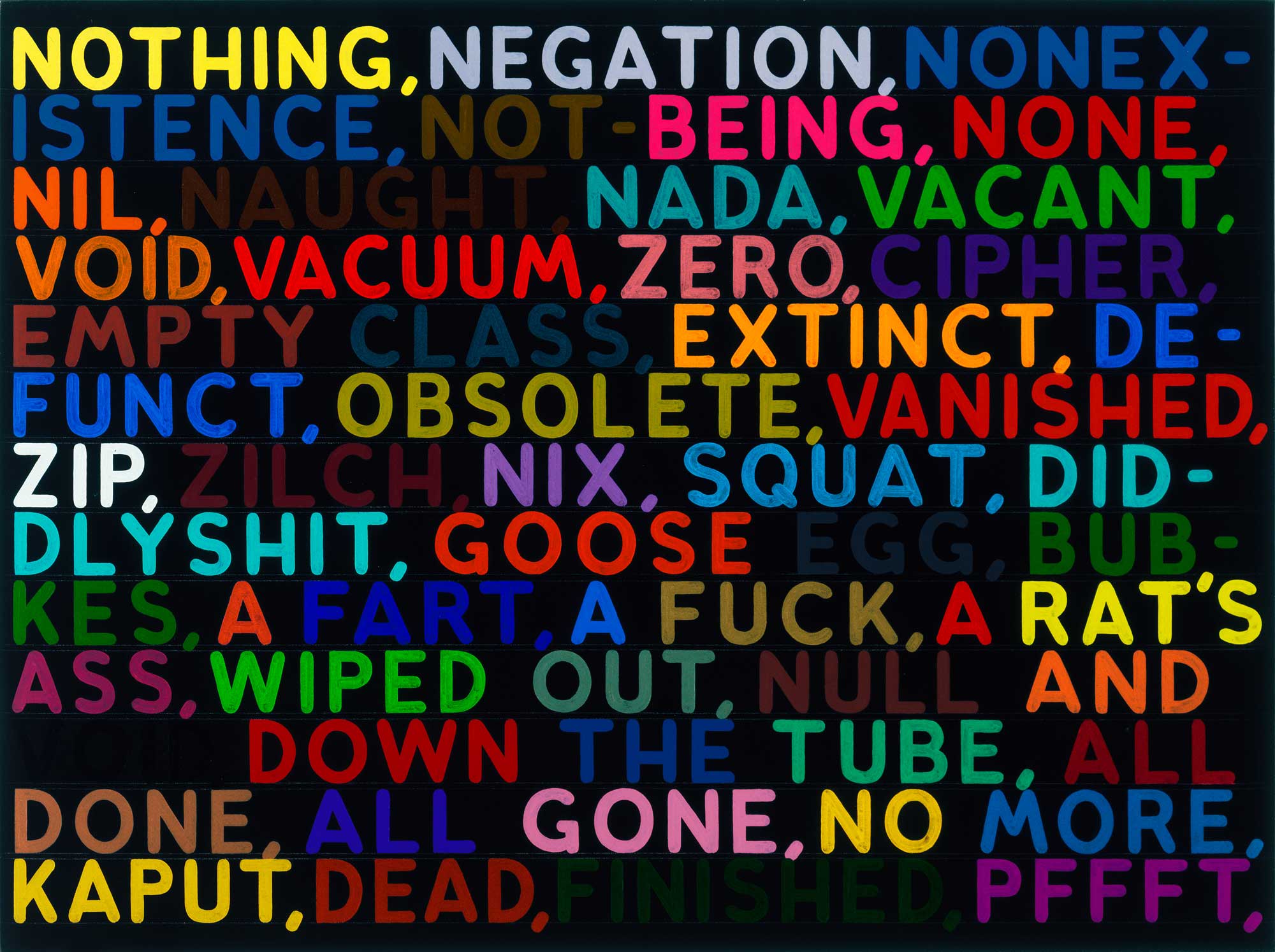

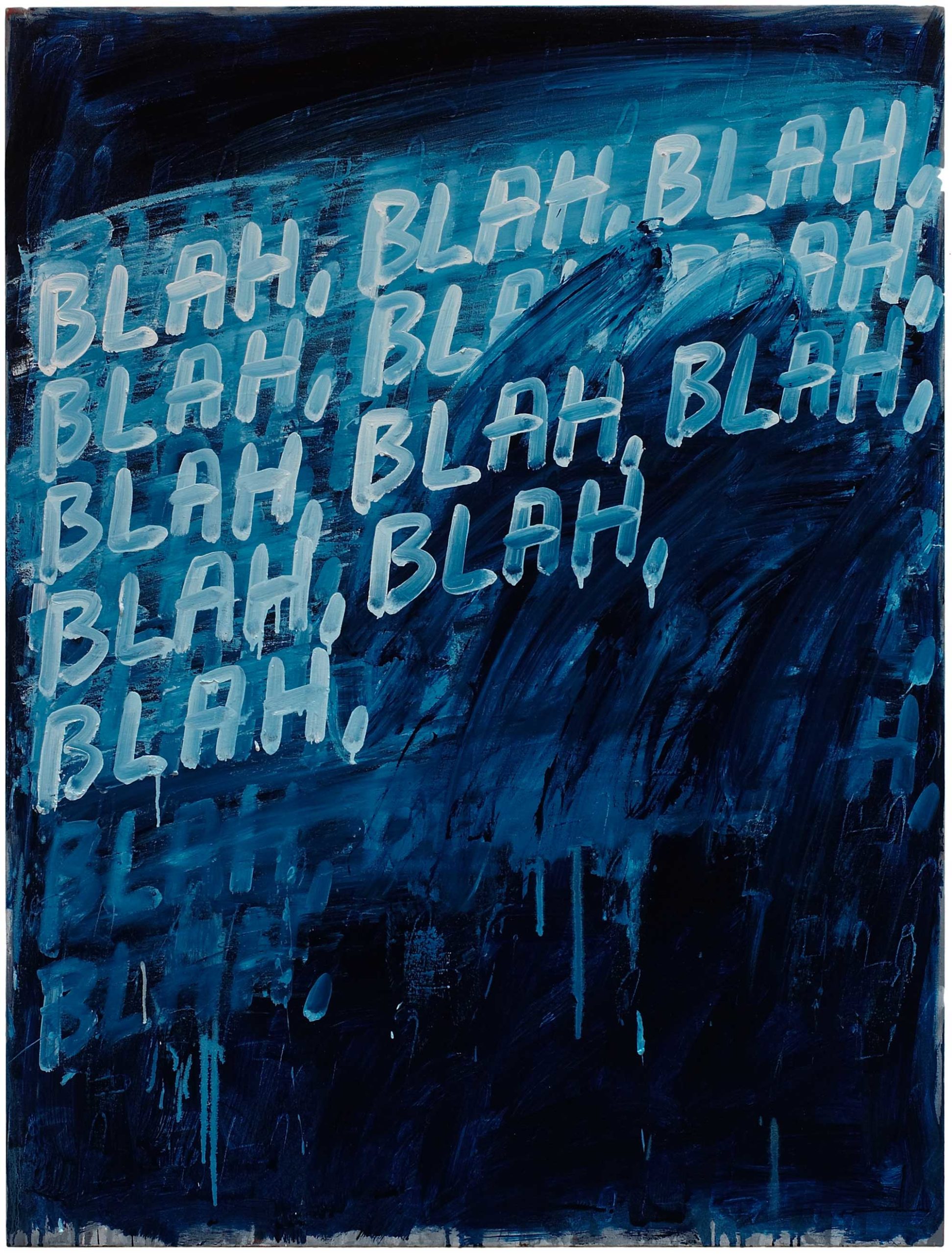

After eschewing the supremacy of painting in his early career, Bochner returned to it with gusto later in life. For the past two decades, he has been best known for his wickedly funny canvases of visual-verbal hijinks—“BLAH, BLAH, BLAH” being one of his most famous assaults in the painted form (others might tell you to “FUCK OFF!!,” or offer up a special kind of urban koan, “A FART, A FUCK, A RAT’S ASS”). Bochner, at the age of 81, still seems ready to pick a few fights. Out at his house on the North Fork of Long Island, Bochner spoke to his old friend, the painter Carroll Dunham, about why Italy was such a savior to his sensibility and why he didn’t mind serving as the bad-boy American interloper. – CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN.

———

CARROLL DUNHAM: If these were normal times, we would have seen each other fairly regularly over the past year. But in fact, the last time I saw you in person was at the opening of that exhibition you put together at the Magazzino. I think that’s the only social event we’ve been to in ten months.

MEL BOCHNER: Yeah. Us, too.

DUNHAM: It was a fantastic show. Tell me how it came about.

BOCHNER: I met Nancy [Olnick] and Giorgio [Spanu, the founders of Magazzino] at an opening, and we struck up a conversation. They’d seen a show I’d done with Boetti at Totah [Gallery] in 2016, and I think they wanted to broaden their scope so as to not only show arte povera artists. I think they thought the Boetti-Bochner show was a model of some kind. They asked if I’d be interested in redoing it and I said, “Not in the same form, but maybe if we’ve added someone else who’s been important to me, like Fontana.” They were 100 percent on board and that’s where we started.

DUNHAM: I’d known about their amazing arte povera collection. It’s great for you to get involved and bring a crossover into contemporary American art.

BOCHNER: Well, my idea was to enlarge or recast the context in which my work is seen, because my work was basically first accepted in Italy. I was never sure why, other than it seems the Italians have a propensity for something called “the avant-garde,” which dates all the way back to futurism.

DUNHAM: When I first knew about your work in the 1970s, I would see a lot of catalogs of these beautiful black-and-white installation shots of exhibitions you had done, which always seemed to be happening in Europe in these old, rundown spaces that still weren’t really being used in the States. The whole aesthetic seemed so amazing and exotic to me and my friends at the time. To this day, I still have a strong association with Italy as the place of origin for what you do.

BOCHNER: That’s true. There was a greater sense of freedom for me over there. The first show I had was at [Galleria] Sperone in Turin in 1970. At the opening I met the gallerist Franco Toselli, and he said to me, “Would you like to do a show at my gallery?” “Yeah.” “Well, we can open it in two weeks.” And I said, “What? Two weeks?” “Yeah, why don’t you stay in Italy for a couple of weeks and open the show?” It wasn’t like New York where everything is scheduled a year in advance.

DUNHAM: It’s such a great way to imagine an art scene working. That kind of approach is unimaginable to those who have only known the art scene of the last ten years.

BOCHNER: Doing those kinds of shows also allowed for a sense of spontaneity, which really affected the way I was working. You would go to Milan and you’d see this space, and you’d make something. And then before you knew it, you were at the opening and everyone was congratulating you and you’d say, “Wait, I don’t even know if I like what I did yet!” It was a kind of existential phenomenon.

DUNHAM: You’re kind of describing an early version of what became this ubiquitous festival system. Artists traveling all over the world, doing installations at this or that biennial. But yours was much more free. My friends and I were about ten years younger than you, and I think that’s really what attracted us coming into the art scene and looking at what was possible. You could bein an abandoned factory somewhere with some stones and some chalk, and make something important. It just made so much sense. That’s not so much the case anymore since you focused on painting, but that’s how you began.

BOCHNER: That’s true. I remember being in Milan at the Toselli Gallery in 1970 for my “Theory of Painting” [an installation of blue spray paint on sheets of newspaper laid across the gallery floor]. I was a completely unknown artist. I’d never shown in Milan before and nothing had ever been written about me in Italian. But I was supported. The gallery was packed at the opening. Packed!

DUNHAM: You must have thought that you’d really arrived.

BOCHNER: I had arrived. And I wonder, “Where the hell did I arrive?” I had no idea. And then there started being collectors’ support. I remember one guy in Milan saying, “My family owns this factory, which is completely abandoned. Would you like to do something there?” “Yeah, sure. Why not?”

DUNHAM: You and I first became friendly in Italy. I’d never been to Europe before and was in my early twenties. I was working as a studio assistant around artists you knew, but we met in a giant, empty underground parking garage, a complex of concrete. I was assisting someone on installations and you were there installing your work with your suitcase of medical tools!

BOCHNER: You helped me, too, on that installation.

DUNHAM: Even with institutions like MASS MoCA that attempt to repurpose abandoned industrial sites, I still haven’t seen anything like it since.

BOCHNER: I don’t think there was a precedent for it either. But, of course, all that work was ephemeral. It only exists now in those black-and-white reproductions in Italian catalogues and magazines. That’s actually, in a way, what I wanted out of the Magazzino show—to reopen that context where my work first entered the stream, which was minimalism. It was also that my work had a lot to do with what was going on over in Italy. And in Germany, too, where artists were also improvising and making things up as they went along, and abandoning fixed boundaries for objects and ideas. It was a very heady time. There was so much political turmoil in Italy by the late ’70s, between the Red Brigades and all the kneecapping and the murder of [the Italian prime minister] Aldo Moro, that it all just dissipated.

It dissipated.

DUNHAM: You mean the energy of the art scene there?

BOCHNER: The energy of the art scene and the energy of the collectors. There are no institutions in Italy—there’s no MoMA, no Whitney. There’s a museum of modern art in Rome [the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna], and it begins in 1750.

DUNHAM: Isn’t there an anecdote about how Boetti and his crowd were at first irritated that there was this American showing alongside their work in Italy, like you were an interloper?

BOCHNER: With Boetti, there was a great deal of hostility, which later dissipated, and we became friends. The issue was that Italian galleries were having American artists come over. All they needed to do was buy a cheap airline ticket and put you up in pensione for a week, and they had an exhibition. In other words, they didn’t have to ship any paintings. They didn’t have to build crates. They didn’t have to get permission to bring things into the country. That explosion of American artists in Italy also had an economic background.

DUNHAM: And they must have already been annoyed by the American cultural effort in Europe after World War II.

BOCHNER: That’s really true, but then it balanced out because between [the gallerists Leo] Castelli, [Ileana] Sonnabend, and John Weber, they were showing practically all of those artists in New York by 1973 as well.

DUNHAM: Was Lucio Fontana around Milan when you were?

BOCHNER: I think he had already died. I first became aware of him as a student in 1961 at the Carnegie International. I went through the exhibition and thought I was pretty hip at the time, although I was completely provincial, but I liked [Willem] de Kooning. I liked [Franz] Kline. I liked [Robert] Motherwell. I could even make room for Barnett Newman. But I walked into the last room and there was this big blue monochrome painting that had been slashed right down the middle with a knife. And I was shocked. I ran to the guard, and I said, “Oh my god, somebody just slashed that painting.” And he laughed and said, “The artist did it himself.” “What, why would he do that?” And the guard said, “I don’t know, it’s just modern art.” And it was, of course, a painting by Lucio Fontana.

DUNHAM: Were you appalled or intrigued?

BOCHNER: I was appalled. I was shocked. Barnett Newman had a blue monochrome painting in the same show. But this slash with a knife was like being punched in the stomach. It was such an aggressive moment.

DUNHAM: I think everyone remembers their first experience with Fontana’s work. I first thought it was stupid. It wasn’t even irritating. It was a put–it–in–your–modern-art–book, hang-it-in-an-airport kind of thing. But then I had an epiphany and flipped on the question of what it meant, and it all just turned around. It’s those kinds of experiences that are really precious, where you go through a thing and come out the other side.

BOCHNER: It turns your head around and opens it up. There are certain things that open up the doors to what’s permissible.

DUNHAM: Do you know anything about what Boetti’s generation felt in terms of a debt to Fontana?

BOCHNER: I have to admit, I never spoke to any of them about Fontana. My guess is that they thought it was decorative. A lot of fun Fontana is decorative. By the time I arrived in Italy in 1970, it was basically old news.

DUNHAM: I wonder if it has to do with the fact that he was originally from Argentina. He was a kind of interloper himself, in the sense that he was from an Italian family, but his origins were not Italian.

BOCHNER: I don’t think I was thinking about him that much until I was living in Rome and was approached by a dealer in Milan who wanted me to have a show at his gallery, which turned out to have been Fontana’s studio. It was almost a shock because he had this tiny studio—it was in the basement of a carriage house of a big estate. It was a barrel vault and I couldn’t stand up all the way. I was thinking about those huge oval-shaped paintings that he made with all those punctures. I thought, “How the hell did he paint those in this space?” At which point I said to the guy, “Listen, there’s nothing I can do here.” And the guy said, “There’s a back room. They’ve saved all of his paints and brushes. Would you like to see it?” So we went back there, and I saw this crate in the corner. “What’s in the crate?” He said, “Oh, that’s the Murano glass that he would smash up with a hammer to glue on his paintings.” He pried open the box, and it was like Ali Baba’s cave, with all of these fist-sized chunks of Murano glass in yellow, blue, red, and green. I instantly knew that I’d been waiting for some revelation about how to make those sculptures that I went on to make with pebbles and stones. Since glass is made of ground-up sand and sand is just ground-up stones, it was like finding a pearl.

DUNHAM: You’ve been painting for a long time, but people don’t really think of you as a painter. You never hear, “Mel Bochner, the painter.” You’re an artist. The same is true of Fontana. He was an artist who found a great use for the conventions of painting.

BOCHNER: That’s a really nice way of putting it. Yes, I have been painting for a long time. But I don’t know where or how my paintings fit into the current discourse, as it were.

DUNHAM: They talk a lot.

BOCHNER: They can be loud, yes. But it’s not for me to say. I can’t govern the reception, but I’ve had younger artists say to me, “Well, you’re a painter now. Does that mean you’ve renounced your early work?” “Renounced? Why should I renounce my early work?”

DUNHAM: That’s a bizarre misunderstanding.

BOCHNER: It’s hard for people to see the through-line that goes from the ultra-conceptual, stripped-down, so-called early stuff to the work that I’m doing now, which, let’s just say, I give myself more emotional permission to make. But I don’t think it’s any less conceptual.

DUNHAM: Those are false choices as we know. It’s very interesting to start and end the conversation around Italy because, for me, the through-line is in those early associations you have with Italian art culture and art history. Unless someone who really loves painting has spent time in Italy and spent time in buildings filled with frescoes, they don’t fully appreciate that relationship of pictorial art to architecture. I’m sure there have been other cultures in the history of humanity that have had that connection, but, for us, Italy was accessible. I don’t remember when you stopped painting on the wall as an ongoing aspect of your practice, but those wall paintings were a kind of embodiment of the most stripped-down aspects of Italian fresco-painting culture.

BOCHNER: That’s absolutely the way I thought about them, in terms of their relationship to the space, to the architecture, to the body that was looking at them, and to a certain way of thinking about color. What I was doing was exotic and foreign to American eyes. The fact that the wall paintings were painted over at the end of the four-week exhibition became incredibly frustrating. The through-line there is that I tried to take that energy and put it into a painting on canvas that didn’t disappear immediately.

DUNHAM: Well, I’m very glad you’ve done that.

BOCHNER: I’m glad, too, in the sense that it gives me a chance to look back on my work and see where I think I succeeded, failed, or misunderstood what I was doing. For me, my work makes a spiral around itself. So if the opportunity avails itself to do an exhibition like the measurement piece I did at Dia [“Measurement Room: No Vantage Point,” 1969/2019], why not?

DUNHAM: I’m glad you mentioned Dia. Dia seems to be going back through your generation of artists—like Dorothea Rockburne and Barry Le Va—and accounting for works that they previously haven’t.

BOCHNER: Sometimes you wait your whole life for opportunities that don’t come along. So when they do, I try to make the most of them, and that’s what I did at Dia. I’ve never been offered a space as big as that one, which is the size of a football field. I’ve seen other exhibitions there, and mostly they ignore the architecture. People just put objects here, there, and everywhere. As I walked through it, I thought, “What can I do here?” And the first thing that came to my mind was, “Nothing. Do nothing. Let the space be the object, just find a way to measure it.”

DUNHAM: The measurement confirms what one feels immediately upon entering the room.

BOCHNER: I think it offers a possibility of actually feeling yourself, feeling your own body as a moving object within this enormous space, which you seldom get, other than maybe in football stadiums or train stations, and those are usually filled up with people so you’re not getting to have that personal experience. Just walking from one end of that space to another gives me the sensation of almost weightlessness and the line sort of holds that space in place. It doesn’t disappear into the infinite whiteness of the painted walls.

DUNHAM: It’s a beautiful room. Anything else on your mind before we hang up?

BOCHNER: Not really. We’ve been friends for how many years? About 40 years.

DUNHAM: Honestly, it’s more like 50.

BOCHNER: Who’s counting?

“Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed As Art,” 1966.