OPENING

A Psychic Sugar Daddy Told Devon DeJardin To Start Painting

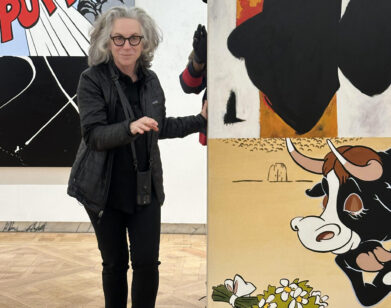

When Devon DeJardin’s fashion company failed, he experienced something like divine intervention when a stranger on Instagram offered him 100 bucks for a ten-minute phone call. He agreed, thinking he could use the money to buy groceries, and found himself talking to a psychic sugar daddy who encouraged him to paint. Eight years later, DeJardin has just unveiled his second solo show at Chelsea’s Albertz Benda, titled Echoes of the Past. “For me, it’s been this kind of cosmic roller coaster,” DeJardin confesses, one leg swinging off a chair in a back room of the gallery. The show, which remixes the works of the old Dutch and Flemish master painters Dejardin admires, tracks with the sense of mysticism and serendipity that has impacted the painter’s own career trajectory. Here, classic paintings are reimagined with secular “guardians,” as the artist describes it. “I’m not saying you need to believe this and that,” he clarifies, “but we should probably look externally to something greater because that’s probably what’s going to bring us the most peace, the most joy, and the most patience and kindness.” And though DeJardin won’t deny that something like fate has tipped its hand, it’s clear a whole lot of work has gone into this exhibition, too. At the opening of Echoes of the Past last week, he talked to me about theology, overnight success, and art world politics.

———

ELOISE KING-CLEMENTS: How was today?

DEVON DEJARDIN: Today was nice. I took a long nap. I walked around Central Park for six miles. I came back to the house. I took another nap, and then I woke up.

KING-CLEMENTS: You can sleep before something like this?

DEJARDIN: I’ve worked really hard coming up to the show, so this is the first kind of break I’ve had from being in the studio and painting. I feel like in the past, for the shows, I really worked myself up. For this one, I’ve just felt really calm. And I feel like it’s cool to be in a different city and obviously have a good turnout and not be overwhelmed. It’s just nice to be cruising.

KING-CLEMENTS: What’s your relationship to work now?

DEJARDIN: When I’m about to ship the work out to a gallery, I’m at a point where I’ve sat with it for six, seven, eight months, sometimes a year. I’m tired of seeing it in my studio. I don’t even know if I necessarily like it anymore. I get really stressed out and then it disappears for a month. And then, this is the first time I’ve seen the work in three months. So, for me, it’s almost exciting to come back because I remember the work. When I get to come to a night like this and see everyone around it and interacting, I get to experience the work again for the first time.

KING-CLEMENTS: Okay, so you’re from L.A., right?

DEJARDIN: I’m from Portland, Oregon. I moved to Los Angeles when I was about 21, right out of school. I just turned 30. So I’ve been there for about, geez, almost nine years now. It’s a city that goes up and down. I think L.A. is having a renaissance with art galleries and artists emerging from the shadows. But New York has always been seen as the pinnacle. This is where real artists were born. It’s intimidating showing in New York because I feel like you actually are presenting yourself to the best of the best. But I just find myself in Los Angeles because I’ve been in the West Coast my whole life. New York has never been the city for me to live in just because I’m a very anxious human.

KING-CLEMENTS: It makes you more anxious?

DEJARDIN: It makes me more claustrophobic. My anxiety has stemmed from claustrophobia, so being around a lot of energy is hard. I bow down to the people here that can just fully operate. I’m like, “You are savage, and I love you and you got it. But I am not there yet.” Hopefully one day…

KING-CLEMENTS: I read that you started painting because a psychic sugar daddy told you to.

DEJARDIN: He’s here. He’s in this building.

KING-CLEMENTS: [Laughs] You have to introduce me to him.

DEJARDIN: I will.

KING-CLEMENTS: Can you tell me about that?

DEJARDIN: I was in men’s fashion for about five, six years. I got to a point where I was not doing well anymore with it.

KING-CLEMENTS: What were you doing?

DEJARDIN: I had my own individual label with my last name attached to it. And I was doing production for other companies in L.A., helping them produce their garments in other factories. Me and my best friend were running that. I got to a point where I spent all my money trying to develop this luxury menswear line that was honestly just not good. So I was scrolling on Instagram and there was a DM request, “Hey, I’ll pay you a $100 to talk to you for 10 minutes.” I was like, “That’s kind of weird, but whatever. $100 will give me some groceries for the week.” I got on the phone with this guy, he’s like, “Hey, man. Are you religious? Are you into spirituality?” I was like, “Well, I just studied world religion for four-and-a-half years. That’s a loaded question. I don’t really know how to respond to that. But I definitely identified with the idea that there’s something else out there.” He was like, “Okay, well, I’ve been following you. I’ve been praying for you. I don’t know what you believe, but I think god’s telling me to tell you start painting. I think it’d be really good for you.” And I was like, “Okay, cool, man. Good to talk to you. My Venmo is this.” Then a week later I was driving past a craft store and I was like, “Maybe I should grab a canvas and see if it’s some divine moment.” Got back to the house, started sketching on it. I was like, “Oh, this is kind of fun.” I sent him a picture. I was like, “Hey, man. Just to let you know, I’m trying this out.” He’s like, “Keep going,” just a subtle encouragement from afar. Within six months, I sold my first piece to a friend of a friend. It just started to roll out.

KING-CLEMENTS: Okay, so many questions. You’re still in touch with this guy?

DEJARDIN: Yeah, yeah. I’m in his wedding in two months.

KING-CLEMENTS: So you guys became friends?

DEJARDIN: Yeah, we became really good friends, actually. Because about six months after doing that phone call, I had sold to a couple of prominent collectors. And everything started to, I don’t want to say “blow up” because that’s not the right term, but it was really like, “Hey, we want paintings.” I got my own art studio in L.A. I had sold $1,000 worth of stuff, just painting and painting and painting. I got approached to do my first show in Los Angeles in 2019 with a group called Coates and Scarry. We rented a building, did a really grassroots exhibition. The show sold out two-and-a-half weeks prior. We had 800 people show up. And I was like, “Yo, this shit’s really real. I don’t know what this guy did or what he said, but it’s happening.” And it gave me that encouragement to keep going.

KING-CLEMENTS: Wow. So, you started selling a lot. The art world seems a little intimidating. How do you balance that when you’re in your early 20s?

DEJARDIN: I was 22 or 23 when I got the phone call. I think I started taking art seriously at about 24. It’s been about six years. I don’t know. I never thought I was going to be a painter, I’m self-taught. I do what I do because I love it. And it’s become a passion after being instructed by someone else to try it, right? I take what I do very seriously as far as the technical process, how I structure my shows and what I’m trying to express. But at the same time, I have no ego attachment to “making it” in this art world because it’s never something that I thought I was going to do. For me, it’s been this kind of cosmic roller coaster. Every time I come to a show I’m like, “I can’t believe this is happening.” I call my mom. That’s kept me so planted on the ground. This is definitely the profession I want to be in. I want to do this the rest of my life. But at the same time, if it doesn’t work, it’s provided me so much joy and so much understanding of who I am as a person that I don’t care if it doesn’t work. I never thought I’d have a couple hundred people at a show in New York.

KING-CLEMENTS: It must feel really good.

DEJARDIN: Yeah, it’s cool.

KING-CLEMENTS: Are you being wined and dined?

DEJARDIN: I mean, I think that’s all part of it. Everyone wants to meet and have dinners and whatever. I enjoy it. I like being around people. I always feel like the best research you can have on the industry is being around the players that actually understand how it moves. So I enjoy getting to sit with collectors and board members of museums and getting to understand. There’s a lot of collectors here tonight that have come from different countries and different states just to be here. I send them Christmas cards. I want to meet everyone and talk to everyone.

KING-CLEMENTS: Can you talk a little bit about the work?

DEJARDIN: It’s called Echoes of the Past. I was really interested in the idea of Dutch and Flemish old master painters that did these beautiful portraits of high society, royalty, kings, queens, all these different people that were human figures that were meant to be at the pinnacle of their time period. And for me, what’s interesting is so much of the history that I’ve looked into is that man or woman has failed time after time. And I say “fail” in the sense of letting countries down, letting people down, crazy acts of injustice. So the figures that I create are based on this idea of a guardian. The guardian is a non-theological symbol of protection, something that we can look at and be like, “I know that the spirit within this is meant to serve and protect me as a viewer.” And so I’ve replaced these human figures with this idea of a deity that is meant to guide and serve. I’m not saying you need to believe this and that, but hey, we should probably look externally to something greater because that’s probably what’s going to bring us the most peace, the most joy, and the most patience and kindness. So I’ve taken a lot of these old master paintings and recreated the figure that’s not human and replaced it with a symbol of protection and guidance.

KING-CLEMENTS: Can you talk about the one in the very back with the curtains?

DEJARDIN: So, this is called the “Veil of Power.” It was this idea of having this very royal figure in prompt of this window. When I was going on a tour of the Louvre, I went with a curator. It’s the first time I went to Paris a long time ago. And she was saying how in all these old master paintings, there’s usually like a mountain-scape or this luxurious sky that’s in the background of these windows. And I said, “What does that mean?” And she said, “It’s always supposed to point towards the afterlife.” So all these little windows into this outdoor landscape were actually the artist’s way of showing the viewer that there was something beyond what we see in human realm. That kind of spitballed into replacing these figures that are humans with these deity figures.

KING-CLEMENTS: Is the show’s curation narrative at all?

DEJARDIN: Not specifically in the curation. This is a little awkward of a gallery. At the show I do in L.A., there’s certain pieces that tell stories side by side. This one was more portrait-driven.

KING-CLEMENTS: Do you have a favorite?

DEJARDIN: I really like the piece in the front room. It’s called “The Beginning.” I like the idea of this kind of raw, desolate background. The singular figure standing there with nothing else around it as just the idea of the beginning of a human journey. It’s almost like that stepping out of the Garden of Eden and being in this kind of desolate land and being like, “Hey, this is the start of my human journey.” But know that you have the spirit of protection and guidance with you. So even though you stand singular and alone amongst what could be this desolate background, you are protected when there’s someone there to guide you.

KING-CLEMENTS: It seems like it’s very myth-driven.

DEJARDIN: Myth, theology, world view. I studied theology and world religion in college.

KING-CLEMENTS: What’s your favorite myth?

DEJARDIN: There was a book called The Pilgrim’s Progress, which is kind of this hero’s tale of a person going through this journey and, along the way, they meet joy as a character and they understand who joy is. And joy teaches them something other. And then they meet pain, they meet turmoil, they meet confusion. And every time he stops somewhere, he has this interaction. Sometimes it hurts and sometimes it helps. But during that process of exchange, you learn something about yourself. I’ve always loved that story.