PERFORMANCE

At 77 Years Old, Pat Oleszko Finally Gets Her Own Gallery Show

Pat Oleszko, photographed by Nolan Kelly.

In 1970, Pat Oleszko moved to New York City from Ann Arbor, Michigan to make a life as a working artist. It was a time when performance and sculpture were joined in creepy, kooky entanglement, when men like Vito Acconci could masturbate under the floorboards of Sonnabend Gallery and call it art. Pat was a performance artist whose robust, extravagant costumes were sculptures in their own right. So she went to Sonnabend and asked for representation. They laughed her out of the gallery so hard that she knocked over one of Carl Andre’s wood-piles on her way out. It seemed like the possibility of legitimate recognition from New York’s cultural elite would elude her. Since then, Pat has done “everything ever since” to stay afloat. Her formative training on the Midwest burlesque circuit undergirds her antic, surreal productions devoted to climate change, 9/11, and the hypocrisies of the Catholic Church. She is quite possibly the only person to ever appear in the pages of Artforum, Playboy, and Sesame Street Magazine alike. And, at 76 years old, her work is finally being recognized in the gallery setting she once craved. Her solo exhibition Pat’s Imperfect Present Tense, currently on view at David Peter Francis, surveys a half-century of sartorial shapeshifting. A few weeks after the show opened, I joined Oleszko at her spectacular Tribeca loft (which happens to be across the street from Richard Serra’s) where we talked about brilliant assholes, melting ice caps, and the collapse of art into entertainment.

———

NOLAN KELLY: I wanted to ask you about your origins, first and foremost. You’re from Michigan. Is that correct?

PAT OLESZKO: Yeah. Both my parents were immigrants, from Poland and from Germany. My dad was an inventor and a chemical engineer, and my mother was totally into the arts. I knew I was going to be an artist. In kindergarten we had to do a self-portrait, and I did one and said, “Well, clearly this is the best one of everyone.”

KELLY: So it started with competition.

OLESZKO: Yeah, it’s always been a competition. I had a crazy wild amount of energy. I wanted to be a puppeteer when I grew up. And then, some years hence, a good friend of mine who is also a performance person said, “Pat, you really are your own puppet.” I said, “Oh…”

KELLY: That’s fascinating.

OLESZKO: Anyhow, I say I’m from Detroit because it makes me sound cool, but it was the ‘burbs, and it was just horrible. But what was very formative in some sense was that we had a great theater department in the public high school I attended. But I never got the parts, I always was the understudy.

KELLY: Oh, yeah?

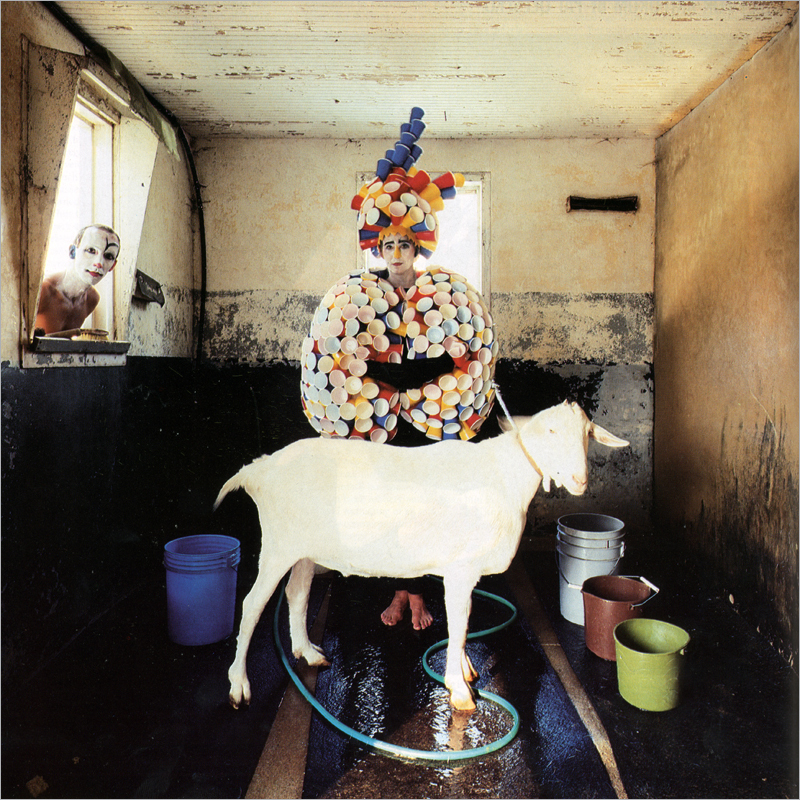

Installation view of Pat’s Imperfect Present Tense, courtesy of David Peter Francis.

OLESZKO: You know how these things go. So I had to make the costumes and do all the sets and shit, I’m like, “Okay, that’s not so bad.” But eventually I discovered this kind of moving sculpture, ‘pedestrian art,’ I called it back in the day. I couldn’t let anybody else wear the work because it was all about me. I was the one that could communicate the idea. A lot of that was from the frustration of not being good enough to be in theater, but then eventually having to make my own kind of theater where I was the fucking star at all times.

KELLY: Yeah, and the director too.

OLESZKO: Yeah, and I made all the costumes, and I did the stage design, and I decided who it was.

KELLY: Right. A one woman show.

OLESZKO: And I’ve done everything ever since. But fortunately, I did get to a point where I said that I could allow other people to wear these characters or these sculptures, and that was a big step for me.

KELLY: That makes sense. And after high school you were studying sculpture?

OLESZKO: I went to the University of Michigan, and I was studying sculpture and ceramics and everything. But I couldn’t weld properly. And so my sculptures, which I wanted to be large, kept falling over. Humiliation is a constant theme in my story. But anyhow, they would fall over and I was too embarrassed in front of my mostly male cohorts, so I started working at home. I had a sewing machine and I started making things. And seeking an armature, I realized I was six feet tall, and I could hang things on myself. That was my eureka moment. Another classic line from my Oleszko storyline: the world is my stage/the world is my stooge. So I was at University of Michigan in the ’60s, and all the campuses were involved in, the interest–

KELLY: A lot of action.

OLESZKO: Yeah. Madison was political. Berkeley was political. Ann Arbor was not only political with the Weather Underground and the first Black studies department, and the first sit-in, but they also had the Ann Arbor Film Festival, which was the first underground film festival that had an enormous amount of culture. Then I came to New York and one of my mentors said, “Well, Pat, we have to figure out a way for you so you’re not just a hired freak at a party.” I said, “I guess you’re right. Okay, what are we going to do?”

KELLY: I love this idea of your body as an armature for sculpture, which is the costume, or they’re interchangeable. To me, it seems so relevant to the type of work that was going on then, especially what the really masculine conceptualists were doing, like tossing lead on a wall or putting their bodies up against planks of wood. This was an era where sculpture and performance were kind of merging into each other.

OLESZKO: Well, good for you.

KELLY: It was my interpretation, but I guess it wasn’t seen that way back then.

Photo by Nolan Kelly.

OLESZKO: No. And I would say that I deal with humor, and take the view that humor is legitimate. Comedy to tragedy is fucking legitimate. I deal with humor, color, and political stuff, in a broad, broad political manner. So that was different than throwing lead against the wall in a minimal space.

KELLY: I know, it’s funny how two things which might be the same kind of act can signify so differently, like if you’re using soft materials and a sense of lightheartedness to the work rather than taking it all so seriously.

OLESZKO: Fucking Richard Serra. Okay. Brilliant. Asshole. Brilliant asshole. That’s not an oxymoron in the least bit.

KELLY: No, you’re right.

OLESZKO: He lived across the street from me.

KELLY: Wow.

OLESZKO: His wife would say hello to me. But he’s walking down the street with millions of dollars in his jeans, walking around like he was fucking crucified. I’m like, “Lighten up, pal, you’ve gotten everything. Every fucking thing in the world.”

KELLY: No, it’s a good point. I love Richard Serra’s work, and then I find him a really difficult character to try and understand. Do you mind briefly repeating yourself about the point about the Met Show that you saw?

OLESZKO: Yeah, okay.

KELLY: Because I think that that’s a really great example of how you can understand a work, both as in front of you, and how it needs to be activated in some ways.

OLESZKO: When I first got to New York I was left out of the galleries, notably Sonnabend, because my work wasn’t minimal enough, or it didn’t have enough theory behind it, or it was too bright, or it was too funny, or it was too whimsical. Whatever it was, I did see a show at the Met, which was a beautifully presented series of costumes from all different geographic areas of Africa. It was in this big, bright yellow room full of vibrant and light, with the costumes on mannequins. And then the rainforest was dark with light coming through the leaves. There was a small TV monitor with a Super 8 film on the screen of the costumes in motion. The exhibition was beautiful, mouthwatering, as they always are, but I was captivated by the movement of the costume, how it became animated. And it was tragically inept, the filming.

KELLY: Not artistic.

OLESZKO: No. No. It was just filming the event with all the gathering of folks. So I said, “Yeah, that’s the difference between showing a work that looks like it’s dead, and a work that is lively.” So I am much more about using the world as my stage, as a piece that’s part of society. I would rather see art walking down the street than have to pay money to go into a museum and see something that’s… Well, of course it looks good, it’s all white walls. I got over that when David [Pagliarulo] said, “Do you want a one-person show?”

Installation view of Pat’s Imperfect Present Tense, courtesy of David Peter Francis.

KELLY: Well, your work looks beautiful amongst all the white walls, but I take your point. Getting into some of the performances you’ve done over the years, is it true that you worked as a burlesque dancer while you were going through art school?

OLESZKO: Yeah. There was a neurosurgeon in Ann Arbor that would date all the flamboyant women. And I defined flamboyant. Bells and beads and patchouli, and everybody knew me, or they could hear me, or they could smell me. So when my time came up for this man to date me, who happened to be married, he invited me to the amateur striptease contest in Toledo, Ohio. And so I got all dressed up for the occasion and when I got there, the proprietor of the theater, Rose La Rose, took me downstairs to meet the strippers. It was the last day of the contest to volunteer from the audience, so I volunteered with this woman who was a telephone operator from Flint, with her beehive hair and stuff. Anyhow, I’m walking up to the stage, I’m barefoot, it’s like November, and the audience was booing. But then they put the music on, and I love to dance, so I literally danced circles around this woman. By the end of the three songs, the guys were standing on their seats, and I won unanimously. So I worked as Pat the Hippie Strippy while I was going through college, intermittently.

KELLY: That’s pretty amazing.

OLESZKO: It was a platform for me to experiment with stuff. Rose, she tried to teach me how to be sexy, but it just really didn’t work. I said, “I’m too big.” But I had a huge following, all the college guys.

KELLY: Unbelievable. I can imagine.

OLESZKO: They had a “We want the Hippie,” sign.

KELLY: The Hippie Stripper.

OLESZKO: It was a play. And it was also the last vestige of vaudeville.

KELLY: Right. I love that about burlesque, its roots are general comedy and vaudeville. But it’s like the striptease began to just take over as the general act.

OLESZKO: Well, they were variety acts, they weren’t movies. Clothes began lessening over the years and stuff, but they were always variety acts. And then the burlesque became more about taking clothes off in an artistic fashion.

KELLY: Yeah. I wanted to ask you about both the vaudeville nature and also, there’s so much comedy in your work. It’s almost the comedy of having a body, having to get dressed up and change shape, the way that clothes can so radically change how you signify, if that makes sense.

OLESZKO: Yeah. Sexuality didn’t ever seem to be static in my life. And so with all of… Excuse me. I have a landline. I have to go answer this.

Photo by Nolan Kelly.

KELLY: Sure. Yeah, no worries.

OLESZKO: Drop that phone. Anyway, I find sexuality very funny. What can I say? You can be masculine. Everybody has masculine traits, everybody has feminine traits. I think that the amount of energy that people spend on breasts and pussies and dicks… I’m a sexual person, okay, like hundreds and hundreds, but the thing is, like, you’re talking about a mere inch or two of flesh with your breasts!

KELLY: Yeah, it’s inherently pretty absurd after a certain point. Of course, the act of taking off clothes in this vaudevillian way is a very long and proud tradition. Anway, it’s, my critic’s kind of reach to try and talk about the lineages and bring this all together, and–

OLESZKO: Yeah. I could talk about my influences like, okay, it’s Buster Keaton, it’s Lewis Carroll, it’s Flann O’Brien, it’s like the Bauhaus. Would you see that in the work?

KELLY: Yes. And those are some all-time legends. There’s a difference between seeing the greats versus the immediate people around you in your own vicinity. That type of influence is often something that critics make more often than real connections–

OLESZKO: Actual people.

KELLY: Yeah. I wanted to talk to you about some of the work at David’s gallery. I love that there’s a little archival section of all of these old magazines that you were in. It’s pretty amazing that you’re on the cover of Ms. Magazine and you’re doing a strip tease in Esquire the same year. That’s covering quite a lot of the pop culture spectrum. It seems like you can work in these very entertainment-based pop-cultural settings, and at the same time, you’re making what is your work, your art.

Excerpt from Artforum Feature, November 1986.

OLESZKO: Yeah. And also in Sesame Street Magazine and National Geographic. And Penthouse and Playboy. Anyhow, that was back in the day when magazines were something.

KELLY: Right. And they have come quite a long way down since then. I was going to ask you if you feel like fine art and entertainment have grown further apart, if there was a time where, especially in Warhol’s pop culture era, great artists were allowed to get into the magazines and the–

OLESZKO: Well, I don’t know if they’ve grown further apart.

KELLY: Maybe closer together?

OLESZKO: Closer together because with entertainment, the minute they sense something that might be good for them, they pluck it out, vis-a-vis graffiti art, all of Warhol’s manifestations. He was brilliant in many aspects, but that was the way that he broke that down so that it became about American culture. And then American culture became something that would suck out all the art out, as long as it was entertaining. That also happened in the performance world, which when it started, and there was no name for it, there were a lot of people working in different fields like Eric Bogosian, Laurie Anderson, and Spalding Gray. Everybody started doing stuff, and then advertising… it’s the nature of the beast.

KELLY: That’s very true, yeah. Well, I know that we’ve talked for a long time, but I was wondering if you could tell me the story about getting arrested by the Vatican, real quick.

OLESZKO: Yeah, right. The project that I did was called “Saints Alive! From Unction to Function,” which involved updating the lives and lies of the saints and taking them out from the churches and putting them back into the piazzas and the countryside from where they came. So I did these characters, and it wasn’t just the Saints, but every time I went into church they threw me out. Except for the Pasta Madonna. Everybody loves the Pasta Madonna. So then I said, “I am going to be the Pope.” I made this character called the Nincompope, which was a little pope, and I made a little platform. And I was working with a videographer whose name was Jesus.

KELLY: That’s beautiful.

Excerpt from Artforum Feature, November 1986.

OLESZKO: And we got along great. And the culminating point was to go down to the Vatican, and I had a gold-plated super soaker that was filled with holy water. I went down there and sat at the fountain that’s outside, and it was really hot. Then I see out of the corner of my eye that there are cops that are running and I have to immediately disrobe.They came over and they arrested me and took me to the headquarters and tried to book me, but I didn’t have any of my IDs. So they took Jesus back to the American Academy in Rome while I waited there for five hours in this place with an armed guard.

KELLY: God.

OLESZKO: They took Jesus to get my catalogs from the show, and he shows them the stuff, and the Chief of Police is looking through it. He’s smirking, and then he’s turning the pages of all my characters, laughing. And so at the end, we’re giving each other hugs and kisses goodbye. But yes, I went there to be the Pope. When I was leaving the academy, the wife of the director, Leila, who’s Italian, saw me going and she said, “Pat, where are you going?” I said, “I’m going to the Vatican to be the Pope.” She says, “Oh. What do you smoke, Pat?” I said, “Why?” And she says, “I want to know what kind of cigarettes to bring you in jail.” So I was much beloved within the academy and within other things, and then eventually by the police.

KELLY: It sounds like you won everyone over, but the Pope himself.

OLESZKO: Well, you know the costumes at the Vatican Police? They are made out of wool designed by Michelangelo himself. Very beautiful. I knew I’d get arrested. I wanted to be arrested by them.