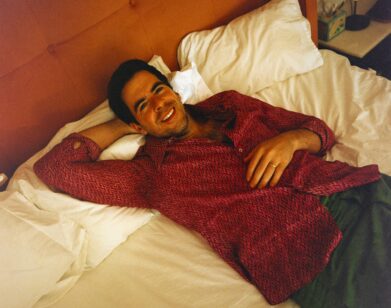

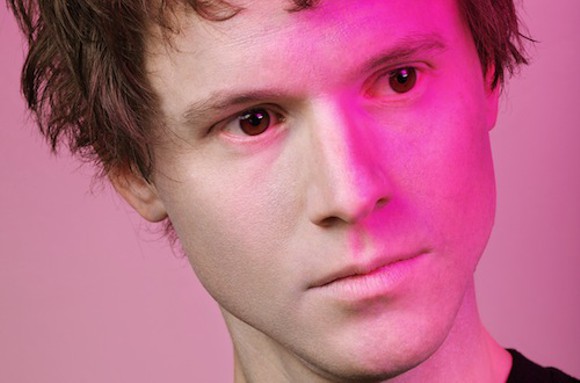

Son Lux Lights Up

ABOVE: RYAN LOTT OF SON LUX

It is late morning on Saturday, and Ryan Lott, the musician/composer behind Son Lux, has had a busy week. His third album, the sparklingly melodic electro-pop work, Lanterns, was released on Tuesday. He is deep in preparation for two Monday night concerts at Joe’s Pub, where he will premiere the album live. And he just underwent a move from Indiana, where he was temporarily living with his wife’s parents, to Brooklyn, where he plans to stay long-term.

“I moved to Brooklyn on my release day,” says Lott. “My rock star, thug life release day celebration happened over the course of 14 hours, driving from Indiana to New York in a tiny car with my dog, the car crammed full of stuff, arriving late in an empty apartment, blowing up an air mattress, and falling asleep. That’s the rock star life for you, baby.”

Lott has amassed quite a résumé to date. NPR’s “All Songs Considered” lauded Son Lux with the “Best New Artist” tag after his 2008 debut, At War With Walls and Mazes. Son Lux’s second album, We Are Rising, was composed in response to NPR’s challenge for Lott to write and record an album in 28 days. He has arranged and programmed for major movies, most recently scoring the upcoming film, The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby. He has performed at Carnegie Hall with the Young People’s Choir of New York, held a weeklong residency at the Joyce Theater with Stephen Petronio Dance Company, and has had his work rearranged by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. He’s collaborated with countless artists, and has released an album with Sufjan Stevens and rapper Serengeti under the name s/s/s.

Interview caught up with Lott, on an unseasonably warm early November morning in Brooklyn, to discuss his artistic process, his myriad projects and future plans, and first and foremost, Lanterns, the best Son Lux album yet.

FRANK VALISH: I want to begin with a question about your last album. You wrote and recorded We Are Rising in four weeks as a response to a challenge by NPR. What did you learn from that experience, and did it give you any insight into your own creative process?

RYAN LOTT: The main thing I learned doing We Are Rising is that I could follow through on my gut instincts, which generally isn’t something I allow myself to do. It’s part of my geeky nature to always thwart my own instincts in order to tap into something deeper. Musically, what that means to me is that I undergo a process of experimentation intended to set certain limitations for myself so that I don’t just lean into my patterns and my habits. That takes a long time, but I didn’t have that leisure with We Are Rising. What I learned in the process is that I can trust myself to follow through with my gut instincts at this point. A year before We Are Rising, I don’t think that would have been the case. I’m really proud of that record. I’m proud of the people who were a part of it. And I’m proud of myself for pulling it off. It really was something that I didn’t think I could do.

VALISH: Did you bring anything about the process of creating We Are Rising to the making of Lanterns?

LOTT: I did a little bit. One thing I did with We Are Rising is that I had to book sessions and record musicians based on what I knew the schedule had to be in order to finish. But those sessions came around too early, and I wasn’t ready. I wound up recording anyway, because I had these sessions booked, we were paying these musicians, they were in demand, and I needed to stay on schedule, so matter what I needed to record. What ended up happening then was that I did some improvised composing in the studio with the musicians, where I would sketch very general ideas. But then in the studio I would tweak things, I would allow myself to change what I was telling them to do, and also allow the musicians to interact with me, saying, “What should I do there? What sounds better on the instrument? What feels more natural on the instrument or what feels less natural on the instrument?,” in order to find maybe a more unique or less idiomatic way to play the instrument.

Having that audio recorded relatively early in the process enabled me to do a secondary stage of arranging with audio, which is where I’m most comfortable. It’s a process akin to hip-hop, where you’re actually manipulating audio and recontextualizing audio, rhythmically and texturally and contextually, switching things around using the audio itself, using the performance itself, embracing the qualities of the recorded medium that are unique to the recorded medium. With Lanterns, I did the very same thing. I recorded very small fragments of performances. I didn’t get too picky with it right out of the gate, and that was a limitation that I embraced, that I could only take a tiny amount of time and a tiny piece of audio. And then once the musicians left and mics were put away, and I was in a different state, and maybe it was a different year—which was the case with Lanterns—I then worked with the audio to bring it to life, to water that flower garden to make everything sort of explode.

VALISH: Did you have a thesis of sorts for this album? Was there a particular sonic ideal that you were trying to achieve?

LOTT: No, what I did with this record is I overwrote. I probably had 16 to 18 pretty thoroughly fleshed-out ideas. I don’t demo. I usually start out with tiny fragments of raw sound and then build something from it and just explore and explore and explore, until finally it feels like it’s turning into something that I can sing over and write lyrics and melody to. So basically, I did a bunch of that until I had about 16 to 18 pretty fleshed-out ideas. And then, from those, certain songs began to emerge as cousins, as family members sort of, and began also to sort of resonate with one another and even inform one another a little bit. That’s when you know you have a record.

VALISH: I understand that you had about 18 songs or song ideas prior to starting We Are Rising.

LOTT: I had a ton. Maybe not that many. I thought I was just going to pause and go back after We Are Rising and finish that record. But what happened was that it felt really wrong to go back in order to go forward. Also, there were certain ideas that I was exploring that I used for We Are Rising, not sounds, not recordings or song ideas, but just more like concepts or experiments. So then going back to the original idea [after finishing We Are Rising] felt wrong, because I felt I just did it and I did it well on We Are Rising That said, there were sounds and little pieces of recordings by musicians and singers that I went back to as new starting points. Stripping everything away and thinking, “Okay, what would I do with that little flute line if I knew nothing else?” Or “What would I do with that little vocal thing if I didn’t know anything else, if I was just hearing this for the first time?” So I took a completely fresh approach to develop Lanterns.

VALISH: It sounds, and don’t mean this in a dry sort of way, like it’s a very intellectual process.

LOTT: Oh yeah, it’s super intellectual. But it’s also very solitary and, as such, it’s sort of imbued with a feeling of a sacred practice. I definitely feel that the time I have to make music feels like a spiritual time. And even though my intellectual mind is really tied up in the process, I just feel like maybe that’s just the thing that’s easier to explain. The thing you can’t really explain is the feeling and the drive to be there in the first place and the reason why you’re using your mind at all, which is a much deeper thing that I don’t really understand. I don’t really understand why when I’m not making music, I feel like I can’t breathe. And that, chances are, has a lot less to do with my mind and a lot more to do with my soul, if you will.

VALISH: I understand that you studied classical piano from a young age, and even studied composition and piano in college. How did this classical training influence the music you desired to ultimately compose, which, although it certainly has organic elements, on the surface it may seem antithetical in many respects to the classical model?

LOTT: I think the training I got in the classical tradition, and the bit I’ve had in jazz, “sophisticated, serious music,” brought a sort of open-mindedness to my music-making and to music absorption, the ability for your ear and your mind to accept things that are outside of the common experience and that kind of have a magic to them by virtue of their strangeness and their complexity. It’s just the big wide world of music, and I think that training in that tradition acquainted me with that region of that big beautiful world, and certainly gave me the discipline to do the tedious, geeky stuff that I do when I make music. I can sit down and play a guitar and sing a song, not really well, but I can do it. I spent most of my time on the other end of the spectrum, learning to execute and create music tediously. I’m actually really glad I did, because ultimately I always found myself in situations where I was also in bands. I was also playing with my friends. In sixth grade, I was playing “Suck My Kiss” in my friend’s basement. In seventh grade, I was singing “Lithium” at the school dance. So I feel like I always had a yin and yang experience with music. I’ve always been able to rock out, and then I’ve always had to take piano lessons, too.

VALISH: I understand that you don’t love to perform live. What’s the process like for you, and how difficult is the process to translate what you’ve spent all this time and effort, intellectually and emotionally, composing into a live setting?

LOTT: The short answer is, it’s just really, really hard. Basically it requires reverse engineering, because you’re working backward from a sound project. But fortunately and unfortunately, that sound project was designed for the recorded medium. My instrument is the studio. When I play my instrument, I’m creating music using the studio. All the other instruments serve it. So going onstage without my primary instrument is like being a guitarist and going up onstage with no guitar waiting for you. What do you do? That’s why performance is painful for me, because I feel like I am always in a strange place with a bit of a handicap. That said, I’m super excited about, for the first time, properly touring a record. I’m doing two shows Monday night, and I have just an army of people helping me. I’ve developed arrangements that are both really broad and vast, with 12 people on stage at once, all the way down to just me on the piano and a guy playing wine glasses and me singing into a microphone. So far, the process has been super difficult and technical. After I get off the phone with you, I’m going to spend many hours programming. I have the core of my band in another location rehearsing themselves. So it’s just a ton of work, but I feel like it’s also a really great opportunity for me to learn how to basically reincarnate these songs for the stage

VALISH: So you’ll be doing more than just these two shows?

LOTT: Absolutely. Just yesterday, I announced a European tour, and soon I’ll be announcing a U.S. tour as well. I’ll basically be touring from the second week in January through South by Southwest, for over two months.

VALISH: I understand there are other projects that are in various states of completion for you, or perhaps complete already. What is next?

LOTT: Actually, 10 days after the Joe’s Pub show, I’m premiering an hourlong string quartet with electronics piece, with a dance company here in New York. It’s being performed by a fantastic ensemble called Acme [American Contemporary Music Ensemble]. I have the copyist working on the scores now. I’ve recently finished an hour-long piece for a small electro-acoustics ensemble, electronics and children’s choir, that’s premiered already in the U.S. twice, but it’s having its Boston premier the same weekend, the 14th through the 16th. I’m producing and mixing yMusic’s next record. The goal there is to create a chamber music record that sounds like no other chamber music record ever made. So no pressure there. And then between the sting quartet and the Joe’s Pub show, I have to finish a record with Sufjan [Stevens] and Serengeti over at Sufjan’s spot. And then I have to put my touring band and set together before the holidays.

VALISH: I can tell what you mean when you say you feel like you can’t breathe when you’re not doing music. I guess you’re breathing pretty freely these days.

LOTT: Yeah. [laughs] Exactly.

SON LUX WILL PLAY TWO SHOWS AT JOE’S PUB TONIGHT, NOVEMBER 4. LANTERNS IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, PLEASE VISIT HIS WEBSITE.