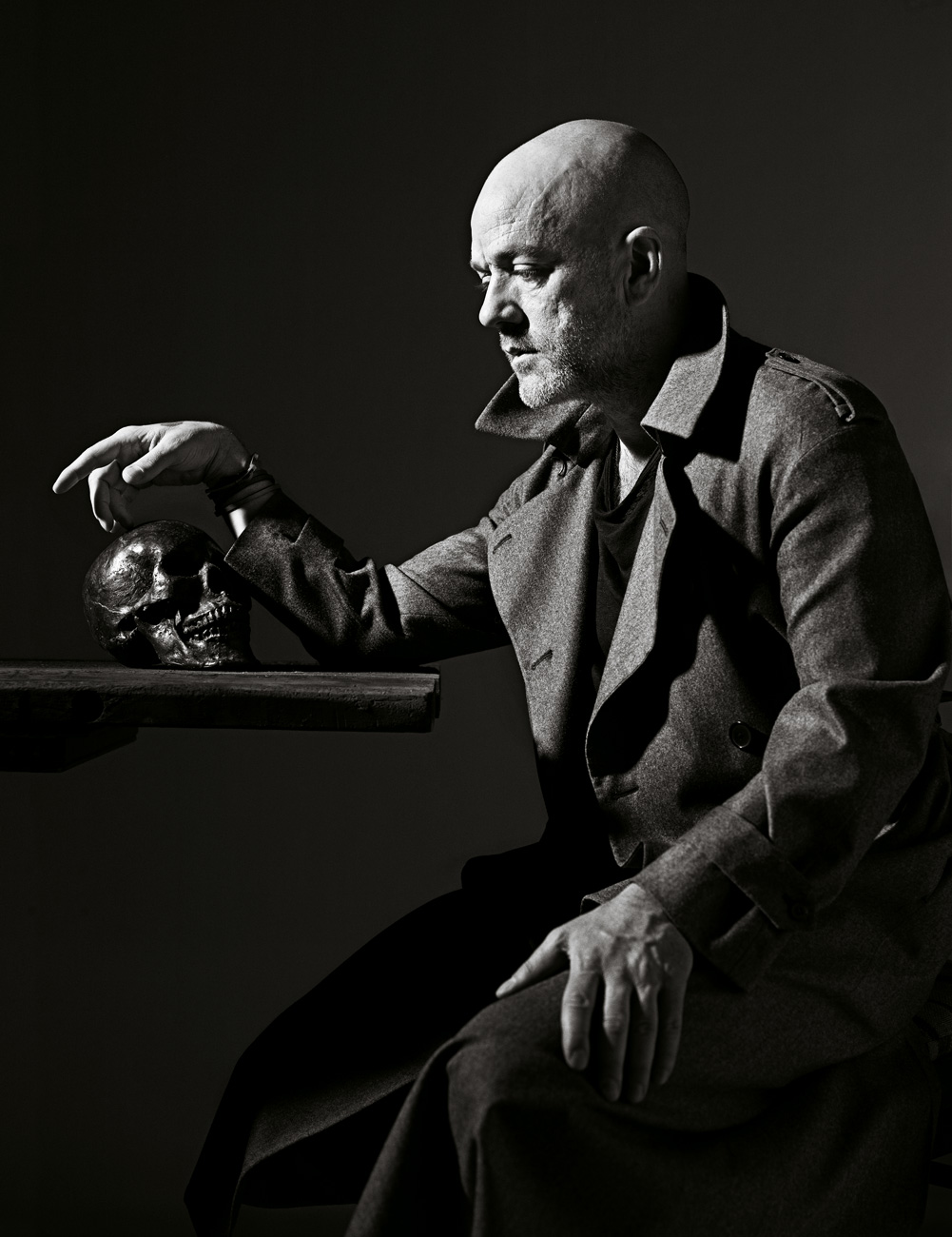

Michael Stipe

Earlier this year, Michael Stipe turned 51, and his band, R.E.M., released its 15th full-length album, Collapse Into Now (Warner Bros.). I highly doubt that there was ever a time in American culture when youth wasn’t worshiped and the new preferred. But Stipe might be the American independent culture’s only certifiable rock legend-so original and imitable that no similar career comparison can be found in the arts-who is actually still in the process of defining what that legend is. Of course, Stipe has always been about eliding genres and confounding expectations. Along with his band members Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry (who retired from the group in 1997), Stipe has built an American band with an American sound that has arguably been one of the most successful among American audiences in the past 30 years, seemingly by inventing a new type of music from scratch: It’s poetic; it ranges from manic melancholy to post-apocalyptic hope; the lyrics and choruses (when there are any) resist glib, sentimental, or cloyingly defiant clichés and yet remain in the head for decades.

Ever since R.E.M. was founded in Athens, Georgia, in 1980 and ushered in a radical, grassroots-youth alternative choice to mainstream pop, the group has been the real thing. Today, the most successful pop acts instantly sign promotional deals and include product placement in their music videos while singing about rebellion. There is hardly a mention now of “selling-out” because the music industry is more desperate than ever to be sold. But early on, Stipe and his bandmates made a commitment never to let their music be used to sell merchandise. Instead they’ve lent their talents to a number of causes throughout the decades-from local politics to global environmental initiatives. But the real surprise about the unlikely super-career of Stipe is that he isn’t being asked to perform the hits from the heyday of his first albums. Collapse Into Now, with its propulsive yet restrained momentum, its lyrical gift of making the listener want to dance and cry at the same time, and its experiments with new sounds, is being described as one of the most powerful albums that R.E.M. has made in years. Yes, that means 31 years into existence, R.E.M. is making new music, their best music, going-forward-and-exploring music. R.E.M. has also teamed up with a collection of artists and filmmakers to create “art films” that accompany each song, providing a richer idea of the album for the YouTube generation. Stipe, of course, has always been involved in the art world (and is an artist in his own right), and R.E.M.’s collaborators on the films include Sophie Calle and Sam Taylor-Wood (who shot her own fiancé, the actor Aaron Johnson, dancing through the streets of London for the song “üBerlin”), as well as James Franco and Jem Cohen. But what is perhaps most amazing about Stipe is that though he has been famous for 30 years, he has still managed to remain something of a mystery. That fact might be the most triumphant. He has stayed human.

In early March, we sat down at his kitchen counter in downtown New York City over sushi to talk about his career.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You’re considered one of Georgia’s native sons. But in reality, you grew up on army bases all around the country, didn’t you?

MICHAEL STIPE: I was born in Georgia. That’s where my grandparents-and all my people-are from. But my family traveled a great deal because my dad was in the army as a helicopter pilot.

Bollen: How did music first get into the ears of an army kid?

I came out of the free-swinging ’60s and ’70s. It was free love, baby. So it’s insane to go from that to Reagan and AIDS. It was like, ‘what happened? Where’s my future?’ Our generation was supposed to be about trying to deal with nuclear concerns and environmental disasters. Suddenly, Reagan is in office, I’m 21 years old, and you can die from fucking.Michael StipE

Stipe: Music really started when I read about the CBGB scene in New York in a magazine called Rock Scene. And then I accidentally got a subscription to The Village Voice when I was 14.

Bollen: Accidentally?

Stipe: It was one of those things that existed in the ’70s that was basically like Columbia House. You send them a dime and you get 12 albums for free-only this was for magazines.

Bollen: Ironically, Columbia House was how I got most of my R.E.M. CDs when I was a kid. I had multiple subscriptions under different names to get as many 12-free-CD shipments as possible.

Stipe: Yeah, well, those magazines were how I found out about the punk world going on in New York. Because of what I read, at the age of 15, I hounded the local record store to order a copy of Horses [1975] for me by Patti Smith. This was in a town outside of East St. Louis, in Illinois, where I was living at the time. To them it was laughable. They ordered it, but they couldn’t have cared less.

Bollen: What happened when you brought Horses home?

Stipe: I sat up all night with my headphones on, listening to it over and over again, while eating a giant bowl of cherries. In the morning I threw up and went to school.

Bollen: [laughs] So Horses led you to bulimia.

Stipe: [laughs] Actually, that was several years later. But I knew right then at age 15 what I wanted to do with my life.

Bollen: You didn’t have any formal training as a singer at that point, did you?

Stipe: No. It didn’t even occur to me. The punk-rock ethos was “Do it yourself. Anyone can do this. We’re not sent from the heavens.” At the time, in 1975, rock stars seemed like these other creatures to me. But the whole point of the punk-rock thing was that “We’re not special. We just have a voice.” You don’t need to be talented. You don’t even have to play the guitar to be a guitar player in a punk-rock band. So I, in a very naïve and teenage way, said, “That’s it. I’m going to be in a band.”

Bollen: You didn’t do anything else artistic as a teenager?

Stipe: I was taking a class in photography. I had my father’s camera that he bought in Vietnam and I was taking pictures that were terrible. I’ve still got some of them. We had a flood years later and we lost most everything. But Horses was that kind of teenage, incandescent, revelatory moment that stuck with me, and I didn’t let go of that dream.

Bollen: There tend to be two different drives that lead young people toward music. One is that music provides an escape; it takes you away from the unhappiness or torture of where you are and makes you feel less alienated-you believe there is a place you fit in somewhere else. The other is a sort of transcendent, spiritual feeling in the purity of music. Which one was punk rock for you as a kid?

Stipe: Those are super-different drives, but I would have to say both are true for me. At the time, I did have an inkling of my sexuality. And I had an inkling that I was different from other people in ways beyond my sexuality. But I didn’t get into music because I thought, Oh, these people will understand me. More than that, it was just a revelation. It was the revelation of thinking, Here’s something that I can do. Of course, it didn’t occur to me at the time-or for years later-that I would actually have to have a voice and write songs, or learn how to arrange and perform.

Bollen: If you were in East St. Louis, were you able to start a band, or was this a dream deferred?

Stipe: I had to get a driver’s license and drive to St. Louis to find the punk-rock scene that was happening there. And there was a punk-rock scene. It was sweet. It was real. It was like everywhere else in the county. It was a handful of people who were feeling the same pull, and, of course, it was like the Island of Misfit Toys in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer [1964]. Just the freaks, the fags, the fat girls, the unbelievable eccentrics . . . They were all drawn to the music, the fringe that was happening in faraway places and trying to recreate it innocently, beautifully where they were. It’s like making capes out of beach towels and pretending to fly.

Bollen: It’s interesting to me that so many interpretations of R.E.M. connect the roots of the music to English punk and New-Romantic bands. In fact, a lot of critics seemed to consider R.E.M. the first American music since the ’60s to break out on its own and develop a stand-alone sound. But your roots aren’t really British. They are much more New York.

Stipe: It was all a mix. Punk-rock records came out and you bought whatever you could find. But Devo didn’t happen for another three years. Sex Pistols didn’t tour the States until ’78. At that time, for me, it was really about CBGB, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, the Ramones, and Television. And then the Dead Boys came in from Cleveland, and X finally formed, and the whole West Coast scene was happening. But New York was where I felt the pull. By the time I was 18, I had absorbed punk rock from America, Britain, and the West Coast. All of it was so dark and weird and different and cool and hot and sexy and rebellious. It was a fist-in-the-air kind of rebellion that I wasn’t getting from the ’70s mainstream.

Bollen: How did you get from East St. Louis to Athens, Georgia?

Stipe: I joined a band in St. Louis and we did two shows. Then my parents decided to move to Georgia to be close to their family. The last thing I wanted to do was move to this cowpoke, hippie town in rural Georgia. I stayed behind and went to college at the University of Illinois at Edwardsville and lived with a punk-rock band in a place called Granite City. We ate spaghetti and butter because we couldn’t afford anything else, and we fucked around a lot. Then I ran out of money and I followed my parents to Athens. Little did I know, of course, that the B-52s were starting their thing in Georgia, and Pylon and the Method Actors . . . There was this whole little scene starting in Athens. I sulked for a year and a half. Then I started the band.

Bollen: I know just from hanging with you around town that your early experiences of being in New York are very potent. When did you finally manage to visit?

I’m not going to do that cheesy thing of lip-synching and dancing crazy-which, I admit, I did from time to time-or acting straight with fake girlfriends, which I never did, not even once.Michael Stipe

Stipe: I came to New York for the first time with Peter Buck at age 19. We spent a week living out of a van on the street in front of a club in the West 60s called Hurrah. It’s where Pylon played. I saw Klaus Nomi play there. And Michael Gira’s band before he did Swans-they all wore cowboy boots and were so cool and had great hair. I was so jealous. I bought Quaaludes at the urinal for everyone and we all got stoned-I mean, totally fucked up-and we watched Klaus Nomi and Joe King Carrasco. I sat on a couch with Lester Bangs at this party someone threw for Pylon and the only thing to eat was jelly beans and cheesecake. Fast-forward 30 years and one of the filmmakers for Collapse Into Now is Lance Bangs, who is Lester’s nephew, I think. Lester was a renowned rock critic. I later wrote him into a song called “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine).”

Bollen: Hmm . . . I think I’ve heard of that song.

Stipe: [laughs] A weird part of that song is that I had had a dream about a party very similar to the one for Pylon and everyone at the party had names that started with the initials L.B. except for me. It was Lester Bangs, Lenny Bruce, Leonard Bernstein. That’s how one verse of the song came about: “Cheesecake, jelly bean, boom . . .” It was fun, that party.

Bollen: Were you trying to move to New York, or just coming to get a look?

Stipe: It was 1979. I had to experience the city. I went and saw the singer from Suicide, Alan Vega. I loved that band so much. We saw him perform at this little club. There was this beautiful girl who took money at the door, who didn’t speak very much English. And there was a guitar player from Texas who was blond and looked like a heroin addict. Everything was so romantic and sexy. I got on the subway and got lost and went up to Harlem. When I got on the subway, I realized that this is where

Suicide comes from. To sit on the subway and hear it in 3-D, and not just from a Charles Bronson movie, but to actually sit on the subway and hear the sound, I thought, “That’s Suicide. That’s where they come from. Now I get it.” The city offered so much to me. It was only years later that I ended up having the experience that led me to write one of the only autobiographical songs of my entire career as a songwriter in the opening track of Collapse Into Now, called “Discoverer.” It’s a song of discovery. It’s about realizing that the city offers you this unbelievable potential and opportunity-all the things you are looking for in your teens and your twenties. That’s what New York offered me. The lyrics are: “Floating across Houston, This is where I am, I see the city rise up tall, The opportunities and possibilities, I have never felt so called, Remember the vodka espresso, Night of discovery.”

Bollen: These lyrics are about your first days in New York, floating across Houston Street?

Stipe: It was years later that this moment actually happened. It’s the feeling itself that took me 25 years to put into a lyric. It’s the same as Lester Bangs and the L.B. dream. It took eight years for that to make it into a song. That surprised me, because I am not an autobiographical writer. I’ll take little elements here and there from things that I’ve actually experienced-counting eyelashes on a sleeping beauty, for example. That’s a moment that actually happened and I wrote it into a song called “At My Most Beautiful.” But the song itself isn’t about the guy whose eyelashes I was counting. It was just a moment I took.

Bollen: For some reason, I always thought your songs were autobiographical.

Stipe: No. I watch people. I’m a voyeur. God knows you’ve seen me in action. I sit and watch. At its best, the lyrics and the work come from some instinctual insight, and then you’re just trying to edit yourself.

Bollen: There is a certain similarity in tone between you and Patti Smith. I know she says she never really got into drugs. And I don’t know your history with drugs. Maybe I’m wrong, and in the ’80s you were an addict but-

Stipe: Only until about 1983.

Bollen: What happened in 1983?

Stipe: I stopped taking drugs. There were a lot of things that led up to it. One thing was that a lover died. An ex of mine died in a car wreck and I was really trashed when I found out about it and I couldn’t cry. I woke up the next morning and I said, “That’s it,” so I quit then. It was horrible. A bunch of people died around that time and she was one of them. I wrote a song about her-that was when I still did pull from autobiographical material. I didn’t really have my voice until after that. Also, AIDS had landed and I was terrified. I was very scared, just as everyone was in the ’80s. It was really hard to be sexually active and to sleep with men and with women and not feel you had a responsibility in terms of having safe sex. And this was the Reagan years, where they were talking about internment camps for HIV-positive people and people with AIDS. The straight community was freaking out because, in their minds, this was a “gay” disease, and bisexual people were passing AIDS from the gay community to the straight community.

Bollen: Do you think your development as a songwriter was heavily influenced by Reagan and AIDS? There is definitely an apocalyptic subtext to your songs.

Stipe: No, I think my apocalyptic feelings went deeper than that. I’m really at peace with how afraid I am. [laughs]

Bollen: What are you afraid of?

Stipe: I’m afraid of everything. I’m not a naturally courageous person, but AIDS really brought it home. I mean, it was right when I was 21 years old and came to New York and saw the first billboard about AIDS. It was like, “Holy shit. This is for real.” It was scary. It was right at the time when I was in a band. Suddenly there were all these people who were available to me-men and women-and I was really having fun. But then there came responsibility and feeling afraid and being afraid to get tested, because you couldn’t get tested anonymously. It was so fucked up.

Bollen: It was a witch hunt.

Stipe: It was. And I think people have forgotten that. Angels in America [Tony Kushner’s 1991 play] is the only thing that I’ve seen in the creative arts that really addressed that feeling. There’s a voice from that era that I believe still needs to be heard. I don’t think it’s my voice, but I did live through it. For example, by the time your generation was coming of age sexually, there was already this idea of safe sex. But that didn’t exist for me. I came out of the free-swinging ’60s and ’70s. It was free love, baby. That was it. We had very liberal sex-ed classes in 1973, a yearlong environmental science class, and then Women’s Lib and Gay Liberation. So it’s insane to go from that to Reagan and AIDS. It was like, “What happened? Where’s my future?” Our generation was supposed to be about trying to deal with nuclear concerns and environmental disasters. Suddenly, Reagan is in office, I’m 21 years old, and you can die from fucking. It was like, “I just started. I’m just hitting my stride. Are you kidding me? I don’t want to die.”

Bollen: By the time I was a teenager, we were pretty much fully indoctrinated, thanks to sexual scare tactics. I remember so many public-health commercials with a B-actor in a fake alley background warning us to use protection or telling us the only real safe choice was abstinence. We were highly frightened of sex from day one. There was no free-swinging ’90s. But for you, it must have been particularly schizophrenic to go from the ’70s to the ’80s like that.

Stipe: Was it Dynasty where Linda Evans kissed Rock Hudson and the tabloids went apeshit for two months that Linda Evans was going to contract and die of AIDS in front of our eyes? And don’t forget how long it took for Reagan to utter the term AIDS.

Bollen: Years. In one biography I read, he only finally admitted its existence when a friend’s straight daughter contracted it.

Stipe: Exactly. But to answer your question, that apocalyptic tenor didn’t come from that period. I’ve had that feeling ever since I was a kid.

Bollen: Was it from your father being in the army?

Stipe: It’s in my dreams. I don’t know where it came from.

Bollen: Do you dream of disasters?

Stipe: Not disasters. It’s more like just after the world has ended, so it isn’t scary. It’s people taking the leftovers and propping everything back up.

Bollen: That’s exactly what I was going to say about how your music has a similarity to Patti Smith’s. Obviously, you both are influenced by a darker grade of music. And you both can be very melancholic. But I don’t find R.E.M. to be nihilistic. There is a constant undertone of joyous optimism. I’m not going to kill myself to Patti Smith or R.E.M.

Stipe: I’ve never written a song that’s hopeless. I’m not a hopeless person. I’m crazily optimistic. I crazily see the good in people. I crazily see the way out of a terrible situation. I crazily try to be the diplomat. If there are two warring factions in my life, I want them to agree to disagree at the very least. I want them to come together. I want peace. When I write, I tend toward melancholy, and the few times that I’ve tried pure joy in music, it doesn’t really work that well. The joy can be through catharsis. I think that’s what I do well, and observation.

Bollen: You say you’re afraid of everything. Were you afraid of success once R.E.M. started to become so popular? Was there a moment of complete panic?

Stipe: I distinctly remember a conversation with my band in the van where I was having a complete meltdown. It was 1984, I think, and I was huddled in the back corner of our van and saying, “I can’t do this. I can’t do this. I can’t do this.” I didn’t want to play any more shows. I just wanted to stop. I went through this difficult time when we were making our third record where I kind of lost my mind. That’s when the bulimia kicked in. And that’s when I got really freaky.

Bollen: Wait, you really were bulimic? I didn’t mean to joke about that earlier.

Stipe: That’s okay. It’s fine.

Bollen: Was it a control thing? Like you needed to control some part of yourself?

Stipe: It was like that thing that happens in prison. People can’t control anything in their environment so they start manipulating their body with tattoos and pumping up.

Bollen: How long did that go on for?

Stipe: About a year. It was rough. We were playing 2-, 3-, 4-, 5,000-seat halls. We were headlining. We had moved out of opening for the Gang of Four or The English Beat. At that point we were playing our own shows and people liked us, but I was unraveling on the inside. I was also vegetarian, trying to eat from fast-food restaurants without meat. I didn’t know how to eat properly and I was starving. I was adrenalized to the eyeballs from performing. I was afraid that I was sick with AIDS. We were playing five shows a week. I even went through a period of abstinence where I didn’t drink and stopped having sex. Which is crazy. Maybe I’m answering too many questions at once here, but this is where my mind was at the age of 25.

Bollen: I can understand living a monk-like existence as a way to protect yourself from vulnerability-from anything or anyone.

Stipe: Well, I was vulnerable every day. Every night that I stepped on stage I was laying myself open, so maybe it was a reaction to that.

Bollen: It’s always surprised me that mainstream America had the good taste to like R.E.M. It doesn’t have the digestible quality the general public tends to look for in its favorite musicians. Was it difficult to maintain that sense of independent identity when the band decided to sign with a major record company like Warner Bros.?

Stipe: We’re fast-forwarding several years here, to 1988. We had broken our backs playing all over the world, and Warner Bros. was able to get us outside of the U.S. They offered distribution all over the world. That’s when it popped. That’s what we wanted. They’d worked with amazing musicians who we really respected a lot and they’d done great things for the careers of people like Neil Young and Randy Newman. When we signed with them, they knew what they were getting. They knew they weren’t going to get some easily manipulated prepackaged pop group. That was not going to happen. What they wanted, I think, was the integrity that we had to offer. What they wanted was the kind of street cred or cache that R.E.M. could bring to them and the chance that we would give them a hit or two. What happened was we gave them a bunch of hits. And we became huge.

Bollen: You’ve collaborated with so many musicians over the years. There was one collaboration with Kurt Cobain that never came to fruition.

Stipe: I was doing that to try to save his life. The collaboration was me calling up as an excuse to reach out to this guy. He was in a really bad place.

Bollen: You knew Kurt Cobain well?

Stipe: Absolutely. I knew him and his daughter. And Courtney [Love] came and stayed at my house. R.E.M. worked on two records in Seattle and Peter Buck lived next door to Kurt and Courtney. So we all knew each other. I reached out to him with that project as an attempt to prevent what was going to happen.

Bollen: The project was an album between you and Kurt?

<>Stipe: No, it wasn’t. That’s where it’s become part of mythology. I simply constructed a project to try to snap Kurt out of a frame of mind. I sent him a plane ticket and a driver, and he tacked the plane ticket to the wall in the bedroom and the driver sat outside the house for 10 hours. Kurt wouldn’t come out and wouldn’t answer the phone. I was in Miami making a record, and I didn’t feel like I could fly across the country for someone who I really admired, who was a friend, a good friend, but not my best friend, you know what I’m saying? I didn’t feel like it was my place to get on a plane myself and go to Seattle. I was doing what I thought was the best thing to do at the time. And, you know, frankly I’m not great with heroin addicts. I tried heroin, but it was by accident. I’m not great with that level of substance abuse.

Bollen: Heroin is a slow suicide. That’s the way I see that drug.

Stipe: I’m kind of quoting Thurston [Moore] and Kim [Gordon] in saying that about not being great with addicts, because they are the ones who said it to me.

Bollen: I want to talk about your music videos and the art films you’ve made for Collapse Into Now. You’ve picked a number of artists to create these pieces to accompany the songs. Looking back, your videos, by in large, have always been art films. I’m thinking of “Losing My Religion.” That’s a landmark piece. Do you always develop a visual language that corresponds to the music you make?

Stipe: Not really. When I hear music as a fan, I see fields. I see landscapes. I close my eyes and see an entire universe that that music and the voice, or the narrative, create. A music video-and any other kind of visual reference-is created by someone else. For me, as a music fan, visuals kind of steal away the purity of the song. My instinct is not to provide a visual to go with a piece of music. But here’s MTV. It’s really powerful. I’m not going to do that cheesy thing of lip-

synching and dancing crazy-which, I admit, I did from time to time-or acting straight with fake girlfriends, which I never did, not even once . . . But we tended to do art films instead, like “Fall on Me,” which MTV played the living shit out of. It’s a single piece of film, shot in black-and-white, on a rock quarry that I flipped upside-down, ran backwards, and put the words to the song over in orange letters. That was the video. It was ’86. We were a big enough name and we had enough cache that MTV wanted to play us, so, along with Michael Jackson and Madonna, they played our upside-down, black-and-white, backward, single unedited footage of a rock quarry with orange letters over the top of it and called it art. That was good and fine, but then that changed in the ’90s. I started lip-synching with “Losing My Religion.” There were a few horrendous mistakes we made, but I own those mistakes. I’m embarrassed by them. I always say when I look back at anything I’ve ever done, it’s with equal dollops of humiliation and triumphant glory. For every great thing we did, there is a very public moment of falling on our faces. But everything that came through us as a band was a distinct vision of R.E.M., and an attempt to somehow contextualize what the four of us-and then the three of us-working together looked like visually. I don’t want to railroad Peter and Mike into my own visual sensibility. It’s a band-it’s all of us.

Bollen: What was the reason for bringing all of these disparate artists together to make films for the songs of the new album? Today, MTV doesn’t play videos anymore, but YouTube certainly has become the next MTV. Were you trying to embrace the YouTube mode of music distribution?

Stipe: The idea was to present a 21st-century version of an album. What does an album mean in the year 2011, especially to generations of people for whom the word album is an archaic term. An album for me as a teenager in the ’70s was a fully formed concept. It was a body of work from an artist I liked or trusted or who excited me. Maybe one of the songs is really poppy and you listen to it on the radio as a hit single and then more of the world is about to find out about this artist by buying the record. Then you realize, “Wow, they’re not one-dimensional. They’ve got all these other things that they’re capable of and interested in writing about.” But now we’re in an age of singles. It’s actually always been more about singles for most of music history. But I wanted to reexamine the idea of the album for generations of people who are not my age, who love music or learning about music or are finding this band called R.E.M. or have just previously heard “Losing My Religion” and “Everybody Hurts” as their elevator music. I wanted to present an idea of what an album could be in the age of YouTube and the Internet. Not from Kanye West, not from Lady Gaga, not from Beyoncé-they’ve got their place. This is what we do. We put together and sequenced the strongest body of work that we could possibly come up with in this moment in time and put it onto this record. I then went to people we’ve worked with in the past, visually, or artists we admire, and had them collaborate on a film. We have Sophie Calle, James Franco, Jim Herbert-who was my art professor in college-Sam

Taylor-Wood, Jim McKay, Tom Gilroy . . .

Bollen: Do you ever feel weird about fame? It does allow you to meet amazing people on this planet and do unimaginable things.

Stipe: I love it. With the difficult parts of fame, that alone makes it so worthwhile, because of the doors it’s opened for me. I’ve worked really, really, really hard at what I do. I give the best I can possibly give at whatever moment in time. But it’s exciting to have been able to meet my heroes-being able to sit down with William S. Burroughs and have a conversation.

Bollen: “Collapse into now” is a line written and suggested by Patti Smith.

Stipe: It’s the final thing I sing, the last song on the record before the record goes into a coda and reprises the first song. The last thing we sing is “20th century collapse into now.” In my head, it’s like I’m addressing a 9-year-old and I’m saying, “I come from a faraway place called the 20th century. And these are the values and these are the mistakes we’ve made and these are the triumphs. These are the things that we held in the highest esteem. These are the things to learn from.” Not in a teacherly or professorial way, but just to acknowledge what was there and then move on. I’m ultimately not so much of a professor as a progresser. And I’m ready to move away from what I consider to be this weird mid-century dream that I feel pulls us as a country, and us as a culture, backward.

Bollen: You don’t seem very shy to me as a person. But a lot of early reviews of your shows commented on your shyness or evasiveness. Do you think you’ve grown extraordinarily comfortable performing in front of others?

Stipe: I was never afraid on stage. That’s where I was the least afraid. I could just do what I do and I had the amplification and the lights. What were they going to do to me? Hate me? Throw things at me?

Bollen: Did you ever have a really bad performance experience where you thought, “I can’t ever perform again. This is a disaster”?

Stipe: I pulled my pants down once and tried to take a shit on stage as a protest to an audience who thought we were a ska band. We were thrown out at gunpoint. It was the West Coast in the early ’80s. We were, in fact, opening for a ska band.