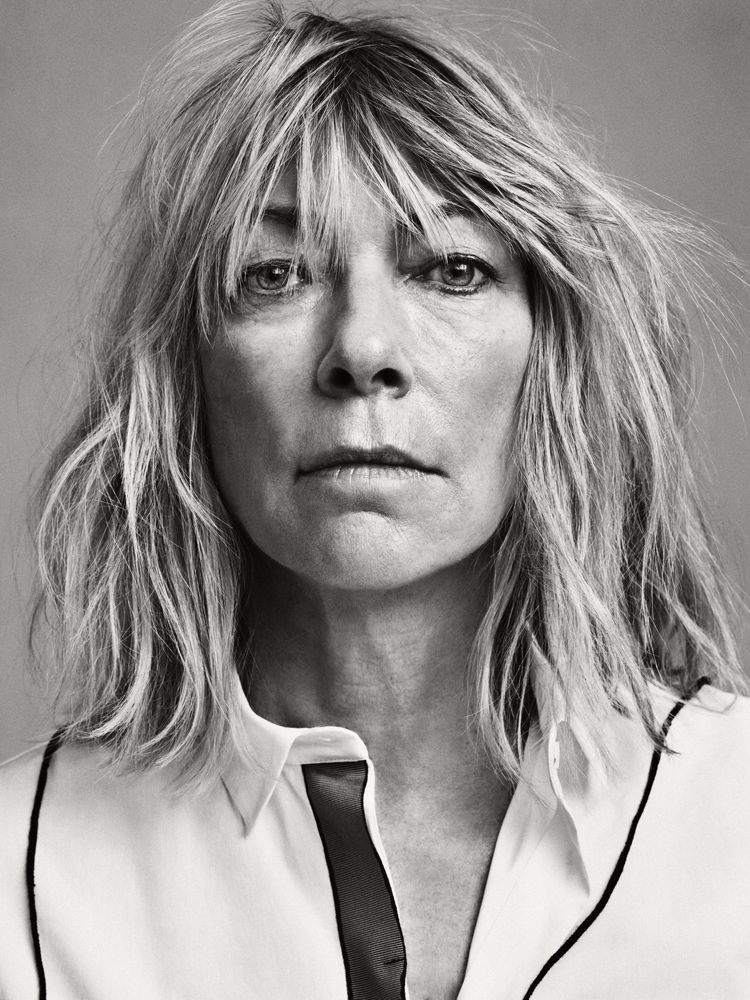

Kim Gordon

I THINK OF MYSELF AS UNCONVENTIONAL. IMAYBE ALWAYS HAD A PROBLEM WITH AUTHORITY, LIKE A STUBBORNNESS ABOUT WHAT’S EXPECTED.Kim Gordon

I met Kim Gordon in 1996. She and her husband, Thurston Moore (from whom she separated in 2011), were in San Francisco playing, and she wanted to talk to me about writing something on their band, Sonic Youth. I was intimidated to meet her and kept putting it off. She is, after all, a rock icon and a force of nature onstage, plus an artist, plus a designer, plus someone I had admired for years. Finally, a friend persuaded me (“Mary, just go and make a friend!”) and I went. The minute I met her, I stopped being nervous. In addition to everything I have noted, Kim was lovely—warm, down-to-earth, direct, and sharp, but also generous and deeply connected. I don’t remember what we talked about, just that it was fun, like life had instantly gotten more juicy and intense.

Since then, I’ve had several conversations with Kim, sometimes in interview form. We’ve talked about everything from porn to motherhood, my personal favorite conversation being a discussion of the 2010 Noah Baumbach movie Greenberg, about a socially spastic, somewhat mentally ill boob. Kim was annoyed that, in her opinion, nobody would make a movie about a female Greenberg:

MARY GAITSKILL: I think I am a female Greenberg; it’s not a great movie.

KIM GORDON: You are not a female Greenberg!

GAITSKILL: You know the scene in the movie where he’s swimming—where he leaps in and you see him spastically struggling to thrash across the pool? That’s how I swim.

GORDON: That would be awesome to see that in a movie, to see the imperfection.

Kim is a force of nature for sure. But for all of her worldly accomplishments and seeming bad-assedness, Kim Gordon has natural alignment with and understanding of the vulnerable imperfect as an expressive force, and a wish to see it acknowledged as a vital nerve in the live body. It’s part of what makes her a force of nature.

I was delighted to speak with Kim recently about her new album, Coming Apart (Matador), which she made with her longtime friend Bill Nace as the band called Body/Head.

GAITSKILL: I think the album is amazing—especially the first song [“Abstract”]. I wasn’t really sure what to expect, but when I heard it, it reminded me of being young back in the ’70s when I heard music on the radio. Where I grew up, in the Detroit area, there was a really good station. Sometimes you would hear songs for the first time on the radio, and if a really special song came on, somebody would turn it up and everybody would just stop talking. I thought the first song on the album would have been that kind of song—if you’d heard it back then. When you’re young, there are things everybody understands, even if they’re not totally ready to understand them. That’s what the song made me remember. It would almost be better to hear it in a moving car, watching things go by.

GORDON: When we play live, we have a slowed-down film behind us.

GAITSKILL: Do you know that film by Carl Theodor Dreyer called The Passion of Joan of Arc [1928]?

GORDON: We were actually asked to play in a festival doing the soundtrack for that film. We’ve never played for an hour and a half before. [laughs] It’s kind of the film that a lot of people choose to play a soundtrack behind. But yeah, I think it would be cool.

GAITSKILL: Have you seen the film before?

GORDON: I must have seen it a long time ago. In film class or something.

GAITSKILL: I recommend it highly. Do you know anything about Linda Lovelace?

GORDON: Oh, I do. It’s funny. This friend of mine, Charlotte Caffey, the guitar player from the Go-Go’s, and Anna Waronker did a small-budget musical that opened in L.A. on Linda Lovelace’s life. It was quite good. I don’t even really like musicals, but it was well done and I actually learned a lot about her life.

GAITSKILL: Her life is a horrific story.

GORDON: Yeah, really horrific. I saw the trailer for the movie [Lovelace] that came out recently about her. It looks really good.

GAITSKILL: They cleaned it up so much; it really pissed me off. To give it a triumphant ending that her life did not have …

GORDON: Oh, they did? Because the musical didn’t clean it up. It went on to Marilyn Chambers as the next girl who was kind of pimped out.

GAITSKILL: I had seen Deep Throat [1972] at the same time I saw Joan of Arc. That’s why I brought it up. When I was 17, my boyfriend was a projectionist at a hippie co-op, and they showed both films there close to each other. So the two are kind of linked in my mind. I was interested in Deep Throat because I had never seen porn before. It didn’t turn me on. But The Passion of Joan of Arc really did. It made a huge impression on me when I was a teenager. I’m amazed that it hit me so hard because there’s nothing overtly sexual in it at all; it’s erotic in its intensity.

You have to let it in, whatever it is. You have to be there, ready to receive whatever it is.Kim Gordon

GORDON: I saw Behind the Green Door [1972]. I think that’s the only porn I’ve ever seen. Do you know Catherine Breillat’s movies? That’s where the name Body/Head comes from. I was reading a book about her films. She’s truly very erotic. I like the way she shoots sex scenes. I mean, some of them are extreme, actually pretty fucked-up, but she always has a bit of awkwardness in it that adds to the erotic. I can almost not watch a Hollywood sex scene now if there’s no gore in it. It’s like, blah, blah, blah. That is pretty much the subject of her movies—sex or sexual identity. In 36 Fillette [1988], there’s a virgin who kind of takes up with this older man and wants to lose her virginity but she doesn’t want to give him control. It’s really all about control and submission—the whole idea of separation of the body and the head. It’s sort of an obvious thing that people don’t really talk about.

GAITSKILL: That was actually my first question: Why is the duo called Body/Head? I guess you just answered it.

GORDON: I try to describe it almost like thinking with your body or your intuitions, especially when it comes to this kind of improv music. You’re listening and thinking with your body, and wanting to lose your self-consciousness. Like any good thing, you kind of go and just forget where you are.

GAITSKILL: It made sense to me why it’s called Body/Head because the sound of your voice is so visceral. But the music sounds almost like the way a brain could function. There’s something implacable about it.

GORDON: Like waves or something.

GAITSKILL: Yeah, but not ocean waves. A brain wave. So the name of the band was inspired by film?

GORDON: Yeah. Bill [Nace] would come over and we’d talk about film and Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd and watch YouTube videos where people would be basically dancing to noise music with psychedelic lights.

GAITSKILL: Why did you choose to collaborate rather than work alone?

GORDON: When you’re working alone, you’re making it all up by yourself. Whereas when you’re collaborating with just one other person, you’re playing off of each other back and forth. But when I play with Bill, I don’t feel like I’m actively listening to him but I know what he’s doing; it’s kind of weird chemistry. The music between us creates this sort of body, almost projecting something that’s inside of it …

GAITSKILL: As a writer, it’s something I’m almost envious of because, when you’re writing and working by yourself, it is a kind of listening, but it’s inward listening.

GORDON: It’s not dissimilar to working by yourself in that you still have to get to the same place in order to create something. You have to let it in, whatever it is. You have to be there, ready to receive whatever it is.

GAITSKILL: In the past, you’ve talked about feeling the audience inside of you when you play. Has that changed? Is the feeling different than when playing in Sonic Youth?

GORDON: Playing with just one other person is a lot easier. It’s also different because Sonic Youth often didn’t have songs. There were lyrical themes, but we kind of made it up—it was different every time. With Sonic Youth, there were more elements to get distracted by when playing with more people. I don’t know whether it’s feeling connected to the audience or just being able to get out of your body, because it’s a combined situation. It’s definitely performative. We play differently if there’s an audience than if we’re in the basement playing with each other. There’s the added element of adrenaline if you’re performing. You’re aware of spatial relationships and the music … It’s like your writing. Sometimes I feel like your writing is performative.

GAITSKILL: It’s performative in the sense that I know that people are going to read it. Before I got published, one of the only ways I could get relaxed enough to write was to say, “Nobody will ever see this. It can be stupid … It doesn’t matter.” When I started getting published, that didn’t work anymore. So, in a sense, whenever you know that somebody is going to be looking at what you’re doing, or having a response to it, it’s performative. I try not to focus on that when I write, because I don’t want to get self-conscious. Reading for an audience is definitely performative—and that’s a whole other thing. Then I’m trying to use my body and my voice to reveal the story in a different way. Some writers are very suspicious of that. Some writers think that’s cheating.

I think of myself as unconventional.

I maybe always had a problem with authority, like a stubbornness about what’s expecteD. Kim Gordon

GORDON: I think you use everything you have. I have a friend who’s a poet and she’s a really good reader. She also plays music, but she’s pretty aware of her body and using it in a way when she’s reading.

GAITSKILL: This might be a dumb question, but if you’re music is improvised when you perform, how closely does it align to the music that’s on the album?

GORDON: It’s really different every time, but we did a bunch of touring. I have such a bad sense of time, but I guess it was last fall when we were just developing as a band. You go on tour and you play and you’re doing improv—and after 10 or 15 dates, you really forge something. And we use those lyrical themes. There are a couple of our songs, “Ain’t” and “Black,” which I’ve done with different people, where most of the lyrics are taken from traditional songs, or other people’s untraditional versions of them. And someone told me I should see this video of Nina Simone singing “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life” on YouTube. It was so powerful and made me realize that I didn’t know that much about her, how really alone she was. There were some really amazing videos of her in the late ’60s in Italy singing this incredible version of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne.” One time she’s singing a cover and stops to talk to the audience and is like, “What a shame to have to write a song like that.” She changes a mainstream song as she plays it. Anyway, it’s like that—it’s different every time. It’s kind of the classic John Coltrane format from Meditations—like, introducing a theme and then breaking it down and then bringing it back. I grew up listening to John Coltrane and jazz, so they were subtle influences. I sometimes think about doing some kind of weird jazz record but I don’t know … It’s on my list of things to do. I don’t want to have to then go promote it. [laughs]

GAITSKILL: What was the first thing that you and Bill did together?

GORDON: Bill and I just started playing in our basement. We did a cover of the song “Fever.” A friend of ours was doing a compilation of some covers and we recorded it, and then we put out an EP and a cassette. It was just nice to be away from the apparatus and machinery, and not promoting something—just the pure music. This band is so free and so fun because it just feels good to play. And Bill’s never been through this. We did promo pictures and he’s never done that before. I guess I feel protective of him.

GAITSKILL: Why?

GORDON: Because he’s a sensitive dude. [laughs] No, I mean, because he’s never had to deal with press, and I think it’s going to be hard in a way. He jokes about the fact that mostly the pictures are of me.

GAITSKILL: On the first song, there is a point where your voice is very strong and then you kind of go into this repeating, mumbling momentum. I like that part.

GORDON: That’s probably our most manipulated song on the record. It’s a loop. The basics of the record are improvised, but then I did go back. I went back with a better mic and redid some of the vocals, and he moved some of his guitar.

GAITSKILL: The record reminded me of the watercolors of yours that I saw the last time we talked—these images of people. They had a clear form but there was also a feeling of dissolving and disappearing. I remember one in particular was mostly just eyes. It was a strong theme of form versus formlessness that I was drawn to. Your voice on the album seemed like it was doing that too. It had a certain visceral tone that was very young, what I think of as the old Kim Gordon. And then other times it would drift off. When I saw your watercolors, we talked about perfection and aging. Perfection to me requires a form that stays. I mean, how can something be said to be perfect or imperfect if it doesn’t have a form? I think there’s something in that which has to do with the way your work speaks to people—to women in particular. It’s about a totally different paradigm: about playing with form and lack of form beyond age and the way you look.

GORDON: The whole idea of women feeling like they have to be perfect—I’ve thought a lot about that because I have a daughter. I read a book called Mother Daughter Revolution, which talked about how feminism never really dealt with motherhood; it was more about getting out of the house. This book was a little bit about owning up to that and seeing what that need meant and passing on that conditioning unconsciously—striving for some level of perfection that you’re never going to attain. You’re always going to feel like you’re catching up, and part of that is just balancing work and motherhood and the whole feeling of needing to please, which I do think girls and women feel more than men. And that’s why when women make a mistake, it does seem like the repercussions for them are bigger.

GAITSKILL: And it seems to me that women, to a large extent, go along with it. They don’t reject it when they could. I’ve been wondering why that is. Sometimes I’ve thought it’s just feminine nature to be that way. In terms of motherhood, women are the primary ones to take care of a child, so mistakes can be potentially disastrous. Also, I hate to think this, but it’s occurred to me too that women feel like they’re in such competition for men that they have to be as pleasing as possible, and if they do anything wrong, they could be rejected, so they become fanatical. They become so insecure about the least things—their shoes, their clothes, their hair, their weight.

When I lived in New York, there were so many girls who were incredibly girly. But when I think about the women I know who I admire, there actually aren’t that many who are really girly. Kim gordon

GORDON: When I lived in New York, there were so many girls who were incredibly girly—pierced ears, the hair, whatever. But when I think about the women I know who I admire, there actually aren’t that many who are really girly. They dress more practically, even if they’re into fashion. They’re smart—it’s not to say that women who are supersexualized aren’t smart, and it’s one thing to play around with your image—but I don’t actually know anyone who walks around Manhattan in four-inch heels.

GAITSKILL: [laughs] I’ve got four-inch heels on right now.

GORDON: Okay, I admire that. But did you get here on the subway?

GAITSKILL: I did.

GORDON: You’re also wearing a T-shirt, so there’s contrast. What I’m trying to say is that it depends on your idea of what makes you attractive and whether it’s for ourselves or for our friends or for an abstract person. And then there are fashion ads, selling objects and clothes, which exist in this parallel universe. Do you know anyone who really looks like that? No. Ads have gotten to the point now where I almost think men are more the target than women—the whole metro-male thing. I have a friend who’s a writer who thinks metro men are really the death of men, or of what a man is. The traditional John Wayne-macho of “I’m just gonna pick you up and take you away and build you a house”—that kind of guy that existed is well past, and the metro man signals that men have become more like women, and they don’t know what else to do, so now they’re consumers, too.

GAITSKILL: I think men are even more fucked-up. Frankly, it’s part of the reason I liked one guy I went out with last summer. He was so old-school. I liked the unfiltered masculinity.

GORDON: That’s my theory why Taylor Kitsch from Friday Night Lights or his character Tim Riggins are so attractive, because they represent that kind of raw sensitive man.

GAITSKILL: This leads to my next question. You have a strong relationship with fashion. To me, fashion is about form and perfection on a nearly frightening level. It’s the opposite of the deep quality of the body that your voice has. It’s almost like you’re connecting opposite poles. Does that make sense to you?

GORDON: [laughs] No. I’m just a visual person. I’m interested in advertising, actually, as much as fashion. I do love clothes. Or I like clothes. It’s a weird thing. Many designers are gay men making clothes for women. Sometimes I think fashion is more of a conversation between men than it is for women.

GAITSKILL: Did you see the punk fashion show at the Met?

GORDON: I went to the Met Ball actually with the Saint Laurent people, which was a trip. I didn’t really look at the show that much. I thought the CBGB’s bathroom was ridiculous. I think it was a history of couture—punk and then some couture. It wasn’t really the history of punk fashion. And I felt like it was very skewed towards European and English designers. Like they had cast models who were kids, wearing English postcard punk attire—Docs and lots of spikes. They were lining the stairs as you went in. It was like the Disneyland of punk fashion or something. I was more like, “Oh, there’s Kerry Washington from the show Scandal that I love.” And that was kind of crazy, being surrounded by people from so many TV shows that I watch.

GAITSKILL: Did you read the piece Richard Hell wrote about the show? He said, “There’s something inherently sad about clothes in themselves, and fashion, no matter how lovely or effective. Clothes are empty.” What do you think of that?

GORDON: Clothes are signifiers and symbols of how people communicate with each other. It’s a breakdown of genres. It’s like social media-high and low fashion are completely mixed up, And now it’s all about the young girl, the jeune fille—the idea that we are all marketed to as young girls. So in a sense, Richard is right. The clothes in themselves are empty. But what they throw off and what clothes mean as signifiers is incredibly interesting—to see what people do with it. That’s more interesting to me than flipping through a magazine or seeing the fall look.

GAITSKILL: I don’t know if I’ve ever told you this, but when I was 5 or 6, I remember going to a roller rink. This was back when people had poodle hairdos and poodle skirts with certain kinds of appliqués on them, and there were a bunch of teenagers at the roller rink going around, and I started crying because it was my first understanding of fashion.

GORDON: Wow.

GAITSKILL: It scared me because I could sense things were being communicated and it was really complicated and I didn’t understand it. It’s exactly that that makes it interesting. And also, scary. [laughs]

GORDON: A lot of artists have an ambivalent relationship with fashion. Maybe it’s about not buying into something.

GAITSKILL: People often describe you as a rebel. Do you think of yourself that way?

GORDON: I think of myself as unconventional, I guess. I maybe always had a problem with authority, like a stubbornness about what’s expected—despite wanting to get some recognition through performing—but also not always wanting to do the expected thing.

You’re always going to feel like you’re catching up, and part of that is just balancing work and motherhood and the whole feeling of needing to please, which I do think girls and women feel more than men. kim gordon

GAITSKILL: I don’t want to talk about the split with Thurston. But I do wonder if all of that has changed your perception or definition of love.

GORDON: Sure, it’s made me think about relationships, no doubt. And basically wonder how anyone can ever really know someone. I’m amazed that anyone has a relationship. But I’m also aware of how pop culture really infiltrates your expectations in a way that even if you think you’re savvy about pop culture, it’s so hard not to have these expectations of what a relationship should be. So I constantly feel like I have to bat those expectations down.

GAITSKILL: I’ve thought a lot lately about “What is love?” Sometimes I feel like I’m too promiscuous with the word because I have said it to a lot of people. And I think love in a marriage is certainly very different from most of the love I’ve experienced. You know, the love between an adult and a child or a person and an animal is very different from marital love or sexual love-it seems like there are so many different kinds of it and we expect it to be the same. But it changes, although I’m not sure it ever really goes away, if you really do love a person. But it can change or become hurt or hidden. It’s very mysterious.

GORDON: The love for a child is more an unconditional sort of love … Although some parents are really narcissistic. In general, I think there is an expectation that love will be unconditional, but obviously it’s not—even after living with someone for years. There are changes and it becomes something different. Gloria Steinem threw a quote around a couple of years ago where she said that your ex-lovers become your family. Which was interesting … [laughs] I don’t know about that. Not for anyone I know.

GAITSKILL: That’s a very dysfunctional family.

GORDON: Maybe she means after 20 years. I don’t know … I feel pretty ambivalent about it right now, quite frankly.

GAITSKILL: I told someone that I loved him and then I thought maybe I was misusing the word because I didn’t really know him. So I looked love up in the dictionary and it didn’t say a feeling that lasts forever. It just said a strong feeling of tenderness and affection.

GORDON: Yeah, people, and especially teenagers, are so over-the-top with the word love—every emotion is on steroids. Maybe you just had a strong desire for that person. Does that mean you love them? It could just be passion.

GAITSKILL: I think that’s sometimes a form of love.

GORDON: I just really don’t think about the word.

GAITSKILL: Before, I mentioned the film [The Passion of] Joan of Arc. Legend has it that the director, Dreyer, made the actress’s life hell. He supposedly made her, like, kneel on stone so she would have the look of concealed pain. She never acted in a film again; it just completely fucked her up. And yet it’s a beautiful film. I wanted to ask you about pain. On the album, I hear a lot of pain in your voice. Your voice is beautiful. But I wondered if you think pain can take you to a powerful place creatively, a place you couldn’t reach otherwise in terms of art.

GORDON: I don’t know. I just work with what I have.

GAITSKILL: I ask because a lot of people will be listening to this new album as some sort of breakup record. If the record just came out without that, people would hear it differently, I’m sure.

GORDON: Oh yeah, people are definitely going to think about the breakup. I mean, it’s called Coming Apart. But breakup records are always the best records. [laughs] I mean, they can either be the worst record or the best record.

GAITSKILL: It’s partly because you’re up against suffering. But I’ll tell you something I’ve noticed about you that is different. Over the period of years I’ve known you, you’ve gotten more articulate about expressing your ideas. In the past, you would hesitate more. You seem to be more confident about saying what you think, like you’re more solid somehow.

GORDON: Oh, that’s good.

GAITSKILL: I noticed it right away.

GORDON: I’ve probably just been thinking about things more. And I’m writing a memoir. A lot of times, it’s easier for me to think while I’m writing. I don’t usually feel the need to actually explain myself.

GAITSKILL: Well, while I mentioned the pain in your voice, there is also a solid presence there in the songs. I think that’s what gives it a dynamic tension—the spirit coming up and expressing itself. I read in a recent article that you said, “Rap music is really good to listen to when you’re traumatized.” Why?

GORDON: I tend to want to listen to melancholy music, but sometimes if you’re feeling too sad, you can’t. Rap music tends to be harsh. It’s not sentimental or sad. I also find myself watching a lot of TV shows about women in crisis, and I seem to be drawn to them all. [laughs] Like Scandal, which I mentioned before. Kerry Washington plays this woman in Washington, DC, who deals with scandals. My favorite line that she always says is, “It’s handled.” Everybody is always freaking out and she’ll just say, “It’s handled.” It seems like there are a lot of roles for women in TV where they seem to be in crisis. Handling it too, being heroes.

GAITSKILL: Another thing you said in a recent article is that women are natural rebels because the rules are made by white male corporate society. And you said, “Why wouldn’t a woman want to rebel against that?” Do you think white society is worse for women than, say, black society or Asian society?

GORDON: I said white because white determines it for black society, too. We’re all living under the umbrella of something created by white men.

GAITSKILL: But there is so much brutality toward women in other cultures that has nothing to do with exposure to white men.

GORDON: I didn’t literally mean the whole world. I guess more Western culture, not exclusive to white men.

GAITSKILL: I read somewhere that you are working on being more open?

GORDON: I don’t know. I’m just trying to be more aware of articulating what I mean. If you’re alone, you can’t be as complacent in terms of reaching out to people.

GAITSKILL: It does make you more open, automatically, when you’re single. In some ways, that can be good.

GORDON: Yeah, you’re out of your comfort zone, so maybe you’re trying things you wouldn’t try because you’re questioning your whole identity in a certain way. Like, I went to Berlin right after Christmas, not this past year, but the year before. I stayed with some friends—I have a lot of friends in Berlin. And it was kind of hard while I was there. You do feel more vulnerable, but then when I came back, I felt stronger, just for having done that trip.

MARY GAITSKILL IS AN AUTHOR OF ESSAYS, SHORT STORIES, AND NOVELS, INCLUDING TWO GIRLS, FAT AND THIN, AND VERONICA. SHE IS BASED IN BROOKLYN.