Doldrums: Spelled With an I

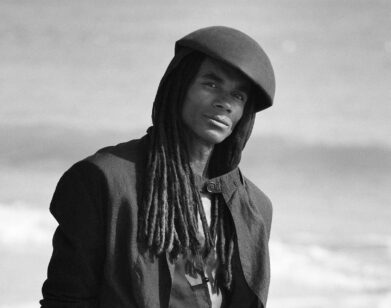

Twenty-three-year-old Airick Woodhead, the Canadian electro experimentalist who records as Doldrums, has already had a few varied chapters in his career. There was his musical tutelage as the son of folk artist David Woodhead, when the young Airick would attend nightlong fireside jams. There were teen years—most of the aughts—spent with his brother Daniel and two friends in Spiral Beach, a pop-rock outfit that made waves in Canada and beyond and appeared in the film Charlie Bartlett. There was a decidedly boho phase that saw Woodhead bum around Europe and the Great White North in search of himself, eventually finding it—part of it, anyway—with a group of like-minded types living and performing at the Toronto DIY space House of Everlasting Super Joy. That gave way to a move to the more art-friendly Montreal and the rise of Doldrums (and a noisier, artier alter ego called Archaeopteryx)—via a Portishead cover, tapes, singles, EPs, and now, finally, an album.

Out this week, Lesser Evil was created over a period of 18 months, and features the sort of clattering collage-pop with which Doldrums has already become synonymous. There’s the ebullient “Egypt,” first released as a single last summer; the Animal Collective-recalling “She Is the Wave,” and “Lost in Everyone,” featuring meandering electronics and something of a statement song inspired by, of all people, Ayn Rand. It’s just one of many topics we touched on when we met up with Doldrums recently in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

JOHN NORRIS: It’s a little funny to say “debut” album, because I feel like I’ve been hearing about you and been into the music for some time now. There was the “Egypt” single last year, before that the Empire Sound EP in 2011 and before that, you had a Live at Silent Barn record out, so it’s been…

AIRICK WOODHEAD: That’s nice that you know about that. That was released as Archaeopteryx. It was up on Soundcloud for like two weeks or something.

NORRIS: With all that lead-up, is it sort of a relief to finally have a full album out?

WOODHEAD: Yeah. Before, I was sort of just making stuff song by song, as I went. And my decision to make a full record definitely changed the process for me of making music a lot, because I was dealing with more consistent sounds, and a broader scope of what I was trying to portray.

NORRIS: Over these couple of years as Doldrums, leading up to this album, has your approach to songwriting evolved at all?

WOODHEAD: I still write the same way, which is you gather your sources, it’s like a collage. You gather your mediums, and then you jam them together, and that’s kind of like your filter of the resources. Whatever comes out is something that’s more mine. Then I usually will hear lyrics or melodies on top of it, and those become Doldrums songs. The ones that don’t, the ones that are more noisy or something, I will just put those on one of the tapes. But I’ve been working hard to make that distinction between those two things.

NORRIS: Two distinctly different approaches?

WOODHEAD: Mm-hmm. Like at this point I play more shows in the kind of free-form setting in Montreal with a bunch of people, or my friends who all make amazing music, and a lot of analog electronic gear and collage and shit. I probably play more shows like that than like “performing” Doldrums songs verbatim, you know?

NORRIS: Will that change with this record, though?

WOODHEAD: Yep. I got three months of tours lined up!

NORRIS: There is so much going on in so many of the songs—how do you know when that’s enough? When a song is “done”?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, that’s an interesting thing. I think about, like, when the last stroke on a painting goes on. Because you can always throw another one on it. But I guess once you get caught up in the momentum of making something, and it takes you a good number of hours to make a track, at least to make like a big track. And that, because it’s like one long session, has a nice like crescendo to it, and then at the end you just have this feeling of completion. It’s very hard to know sometimes. The worst is overworking shit, though. I’d rather stuff be raw than overworked.

NORRIS: I think maybe a lot of newer Doldrums fans may have heard of the space you lived in in Toronto, The House of Everlasting Super Joy, but they may not be so aware of Spiral Beach, even although that band made some noise in the States as well as in Canada. It was like six years you did that, right?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, or more.

NORRIS: Did you reach a point personally back in 2009 where you needed to do something different?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, I think we all did. We wanted to live lives. We were all like obsessive throughout high school about making music. And I just, at one point I just wanted to take off. And that’s what I did, basically. I went to Europe for a little while, just to hang out, I went to Vancouver, and did a lot of stuff, met a lot of people. And eventually I became involved in the Super Joy community in Toronto.

NORRIS: Can you talk a bit about that space, for those who don’t know it?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, so that was my introduction to running a DIY venue, and having that be my pro-economy that allows you to do art and sustain yourself, pay your rent, and at the same time like creating a dialogue between everyone who was involved. And Super Joy was I think very much modelled after New York’s Silent Barn. It seems to me like it originated here.

NORRIS: Was it mainly noise artists?

WOODHEAD: All sorts of stuff. I think the umbrella of “noise” includes so much different stuff. But I think it just means that the emphasis is on live shows, integrity, experimentation, outsider stuff. Sometimes performance art stuff. Like I had so many people pee on my floor as part of the show, and I was like, “Really? Again?”

NORRIS: As part of the show? Was it your job to clean that up?

WOODHEAD: Not my fucking job.

NORRIS: And then you made your way to Montreal. I read where you said that when people ask “What’s the ‘sound’ of Montreal?” that’s it’s not really about that, but more the reason that people are there.

WOODHEAD: Yeah. The thing that I hope the rest of the world is getting is that it’s fostering its artists to be as much themselves as possible, you know? And it’s like that diversity is usually the antithesis of a strong, marketable “scene.” Because you know, we’ve used genre to market music for so long. But on the label, there’s like Sean Nicholas Savage playing amazing fucking old-school songs, and there’s Blue Hawaii doing like soulful electronic music, with like rap singing, they’re so good, and me who’s like “Bbbrrrr,” whatever that is, and there’s Tonstartssbandht, who are these brothers. I guess they live here now, or one of ’em does. And they’ll be doing, like, psychedelic boogie.

NORRIS: A lot of what you do and what you talk about seems to emphasize the idea of individuality and even—correct me if I’m wrong—but going so far as to advocate being sort of selfish about your work. I read one place you said that you feel like “community” has taken over everything and that you even think we are too altruistic of a world. And that was the one place that you lost me.

WOODHEAD: Well, I was reading Ayn Rand or whatever…

NORRIS: It’s so funny you should say that—I can show you in my notes here where it says, “Is he the musical Ayn Rand?”

WOODHEAD: Well, she also has this element of slogan to her writing, which I fucking love. I know she is seen as this capitalist, not exactly the most favored woman for me to be all into. But the ideas are nicely put. And they stand for individualism. There’s that one book where the word “I” doesn’t exist. And just through that, everyone’s mindsets change. And there is no sense of self. Which I think is true in some other cultures, that there is no word for “me.” And yeah, fuck what anyone else wants to do. People should just do what they want to do. But that’s just basic 101, let’s make stuff we feel good about. Any art should make you feel like that, that someone is doing what they specifically want to do. Like, my brother’s record is called Obsession. I think that’s so good. Because it’s the obsession that’s important. It doesn’t even matter what you’re obsessed with.

NORRIS: You know, for all of your reputation for hyperactive, clattering music that you make, there are also mellower moments in your records.

WOODHEAD: Yeah, I think half of Lesser Evil is mellow. Pretty much.

NORRIS: “Sunrise”?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, “Sunrise” and “Holographic Sandcastles.”

NORRIS: There’s an older song, “Copper Girl,” which is a slow jam by your standards.

WOODHEAD: I got mad slow jams! “Endless Winter”…

NORRIS: Exactly!

WOODHEAD: But I think I do have probably some attention deficit disorder or something that makes me make really dense things in whatever medium. But like, don’t we all have that at this point? Cause everything’s just sort of flashing away at you. But one thing I like about this attention-deficit universe is that you can apply that attention vertically, to music. And I think that’s why ambient music, and tonal-based music is really interesting. Because it doesn’t flash at you, it’s not linearly like, crazy, but it can be vertically crazy. Like the tone, the timbre of it can be really interesting. So that the longer you listen to it, the more you feel, and very, very slight changes can elicit stronger feelings in you. And hopefully that’s evident in the music I make.

NORRIS: You seem happy in Montreal, but I get the sense that you are restless, too. Do you ever see yourself living here?

WOODHEAD: I’ll probably live in New York sometime. In the next, like, five years.

NORRIS: Yeah? Do you need like stimulation like that? Geographic stimulation? Environmental stimulation?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, but it’s also like, I did that for so long. If you’re 18 and you look for somewhere for like two years to be your home, it’s like a pretty lost feeling. And so I’m trying to build something around me as my home now. And that’s strong for me and it’s hard, it’s especially hard for me because I am antsy and I do always wanna take off. But even just getting an apartment. I’ve been subletting different places month to month for like two years. And I’m just not good at that stuff.

NORRIS: You’d rather have a permanent place?

WOODHEAD: I’m trying, I’m trying.

DOLDRUMS’ LESSER EVIL IS OUT TODAY. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE. YOU CAN SEE JOHN NORRIS’ COMPLETE VIDEO INTERVIEW WITH AIDRICK WOODHEAD ON NOISEVOX.