LIT

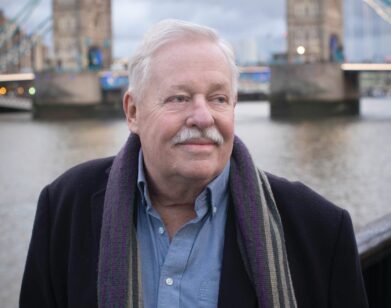

Marissa Higgins on BookTok, Lesbian Fiction, and Her Debut Novel

According to Marissa Higgins, the main character of her debut novel A Good Happy Girl, Helen, is not an easy sell. She’s at times grotesque, a quality reflected on the book’s dust jacket, which features a close-up of a mouth inhaling a sloppy hamburger. Reliant on shots of cough syrup to alleviate the trauma of her parents’ lifetime of bad deeds, Helen also cycles through other distractions: filming her feet for an internet audience and hopping in bed with a married lesbian couple, Katrina and Catherine. She’s rarely truthful in her relationships and more than once seems to lose her grip on reality in speculative contemplations. And yet, despite the mess and discomfort, it’s impossible to look away or not keep turning the page. Higgins, as the novel demonstrates, is enormously skilled at provoking the reader’s empathy for complex, unsavory characters.

When we spoke on Zoom two weeks before publication, the author described Helen as “a poking child who still really wants her parents to reveal themselves as finally good, despite however many things show otherwise.” In our conversation, we discussed this search for goodness as a driving force in the book, as well as creating characters with rich inner worlds, maximizing BookTok publicity efforts, and Sweetener—not the Ariana Grande album, but Higgins’ next novel.

———

SAMANTHA PAIGE ROSEN: I’m so thrilled to talk to you about your first novel. But before we get to the book, I have always wondered where you live, because I feel like you’re always on the beach.

MARISSA HIGGINS: I recently moved to Puerto Rico.

ROSEN: That makes a lot of sense. I feel like that’s a good place to write.

HIGGINS: Yeah, there’s a lot of incredible nature.

ROSEN: I also wanted to ask about the cover of A Good Happy Girl. It’s a close up of someone taking a giant bite of a burger, which does relate to a scene in the book. How did you settle on that cover? Is that you?

HIGGINS: No, but it’s really funny. When I first saw the cover, I definitely felt surprised at how much it looked like me. I received two options for the cover—that one and a pink one that was also really beautiful—but I felt like this one was a little more gritty and gross and communicated the weirdness of the book.

ROSEN: It definitely speaks to the main character, Helen. You can’t look away from her, even though some things are slightly off-putting. I know that at first the book was called The Wives, which makes sense because it’s about a woman who’s entering into a relationship with married wives. I’m curious how you arrived at the title.

HIGGINS: Honestly, I came to the realization that one really successful book called The Wives already exists, and another book called The Wives is also out this April. So I think my agent or my editor asked me to come up with a list and voted on A Good Happy Girl.

ROSEN: The character’s interest in goodness and happiness is so complicated. She’s haunted by the damaging dynamics within her family of origin—she lost a brother in childhood and her parents committed a crime in adulthood that was really personal to her. As you were writing, what did you see in goodness and happiness for Helen?

HIGGINS: I think the idea of someone seeing Helen as good is the driving force, maybe more than anything actually good that Helen can seek. She desires for someone to see her as good. I don’t know if acceptance is really the word, but some sense of being seen as human enough to be baseline good.

ROSEN: That makes sense. I think she seeks it from the wives, and this one line really stood out to me toward the end. She says, “I would still do most anything to be chosen by the people who did not particularly care for me.” She’s talking about her dad and her mom. I wondered if, despite her parents’ crimes and their neglect, maybe Helen still wants to see them as good, too.

HIGGINS: Yeah, I think that’s very wise. If Helen could see them as bad, or at least as not good enough to have some role in her life, I think she would have a whole different world of turmoil. I see Helen as a poking child who still really wants her parents to reveal themselves as finally good, despite however many other things show otherwise.

ROSEN: This is your first book. Were you at all fueled or deterred by the idea of not being good enough? What were the feelings that came along in the process of writing your first novel?

HIGGINS: Honestly, I have a lot of fun writing, I really enjoy writing and editing, so I think drafting and revising is probably the most fun part of it for me. I will say, on submission, I had so many rejections that I completely lost count, so that was sobering and disheartening, for sure. Once I got the offer from Catapult, I was so surprised and so grateful because I had made peace with the idea that it just might not sell. I don’t know that I did myself any favors by writing the book the way that I did. I don’t know that Helen is the easiest sell, so I had some really interesting reactions early on.

ROSEN: People don’t talk about the rejections and the hard stuff. I was actually looking at Goodreads to see if other people had this reaction, but I felt this tug of war in Helen’s narration between the extremely visceral and the out-of-body. I have a couple of theories as to why, but one thing I noticed is this difference between what she’s thinking about and what she says or does. Sometimes, she’s very connected to the things right in front of her, and other times she’s so far away from the people around her, which is why, as you’re saying, she’s not the easiest sell.

HIGGINS: Yeah, it’s a really good observation. I’ve done so many revisions with Helen and my editor encouraged me to ground [her] more in the body. I took that direction and just really leaned into making it super visceral. I find Helen compelling in that she can create whole worlds and emotional arcs and stories that she can ride out just in her own head, while on the outside she tries to perform like a robot. So I see her as moving between the two extremes. Helen’s mind is almost like a creative kid, or a scared kid. They really feel like the monster in their closet is so real. It’s so easy to embellish and their stories can get so rich when recalling memories of something that didn’t happen. I feel a lot of this kind of fantastic escapism when I’m in Helen’s voice, almost like a child dressing up. And then, as a writer, I receive really helpful feedback that people often don’t—what is it called? I struggle with staging.

ROSEN: Like, the physicality of the layout of the room and the scene?

HIGGINS: Yeah, exactly. So that’s always something I have to go back and build in. I don’t know why, when I think about a memory, the logistics of a room is not what I think of. I think of these wild things instead, which is maybe why it’s easy for me to lean into that with Helen.

ROSEN: Yeah, I really wish that I had caught on to her childlike nature. There’s one moment where she wonders if her face has begun to bleed—”my nose hanging from my nasal cavity, eyes out of my sockets”—and it does remind me of the way in childhood, you just catastrophize every little moment. I do want to make sure that we talk about the unconventional relationship in the story, which is that Helen becomes part of Catherine and Katrina’s marriage. Why did you want to explore this kind of relationship?

HIGGINS: Honestly, I think Helen is a character that needs to feel like she is in a game, that she can’t just have a normal date or do something conventionally. She is so resistant to what’s expected of her that I think it would almost feel dishonest to have her be in anything but something so unusual and chaotic from the start.

ROSEN: That’s true. And I remember being surprised at first that Helen is a lawyer, a nine-to-fiver, even though she often works from home. Did you feel like there was a hole in the lesbian fiction arena that you wanted to fill?

HIGGINS: I can’t say that I have read or seen a ton of lesbian throuple stuff, but it definitely does exist. Honestly, I never really think about what my work could add into any of the conversations I’m interested in just because I never contextualize my work among others.

ROSEN: I know you were recently part of the Poets and Writers “Get Out The Word” publicity group that helps early-career writers. I would love to know what you learned from that experience, and especially whether being on TikTok is really necessary for book promotion.

HIGGINS: I really enjoyed the program, and it’s free, by the way, which I feel is so important. I definitely recommend anyone eligible apply. So the woman who ran it used to be in publicity at Riverhead and every week she invited a different contact of hers to speak with us. Publicity is definitely a machine. So if you ever feel like certain books or certain writers are getting this absolutely incredible push, you’re not wrong for noticing that. I wouldn’t say it’s always random. Hearing all of the different creative ways that the publishing machine promotes books was eye-opening. I’ve never received one myself, but I saw some people get these very elaborate, beautiful boxes that their books come in. It opens and then there’s stuff inside.

ROSEN: There is swag in there. I’ve seen that.

HIGGINS: They can even have food or alcohol from the area the book is set in. Some books just get a beautiful, thoughtful campaign, and some books don’t get the same resources. So I do unfortunately recommend TikTok. I have found it really helpful to find BookTok creators on the app who post content for a similar audience to my book. And my publisher, Catapult, sent galleys to a lot of those people who seemed interested, and it does make a difference. And I think having a presence on the app helps you stand out a little bit more as a real person. Unfortunately, I know a lot of writers don’t want to do it.

ROSEN: So much of the machine isn’t in our control. As labor-intensive and annoying as it sounds to me personally, you probably want to do everything you can to help your work sell.

HIGGINS: Yeah, I tried BookTok and Book Instagram and I found the growth on TikTok to be way more useful for about the same amount of effort. There’s so many mysteries with the algorithm. I haven’t sent out any kind of reward or gift, and I’m not doing book events, so I’m just leaning into it hard for now. But the other thing with TikTok is you can upload the same video over and over to different music, and because TikTok Boosts sends you out to an audience that mostly doesn’t follow you, you could batch a few video variations and probably get some new readers.

ROSEN: That’s helpful. You mentioned that you were working on another book while you were selling this book.

HIGGINS: Yeah, the next book is called Sweetener.

ROSEN: That’s an Ariana Grande album too, isn’t it?

HIGGINS: Yeah.

ROSEN: Good vibes.

HIGGINS: It’s a rotating point of view between two characters. One is one of two women who is married and going through a separation, and the other is the woman that she meets on a dating app who is acting as a sugar baby with her but, unbeknownst to her, acting as a sugar mama to her soon-to-be ex-wife. So this other woman, Charlotte, is funding the women’s attempt to foster a baby and get their home together. And while she’s supporting this scheme, the other wife is supporting this woman who is actually supporting her wife. So I hope people find it funny.

ROSEN: It sounds darkly funny.

HIGGINS: Thank you. My editor said it was like a screwball comedy. Lots of people fainting, as humor. I don’t know that Charlotte will be easy for people to relate to either, but I think people will have an easier time because of her narrative. I think of the movement on the page as prancing and bouncing and very performative, like tap dancing through the story.

ROSEN: I do love the idea of a lesbian screwball because the classic screwball comedies were so hetero and so phallic.

HIGGINS: I have many edits ahead of me.

ROSEN: At least you can make them from Puerto Rico.