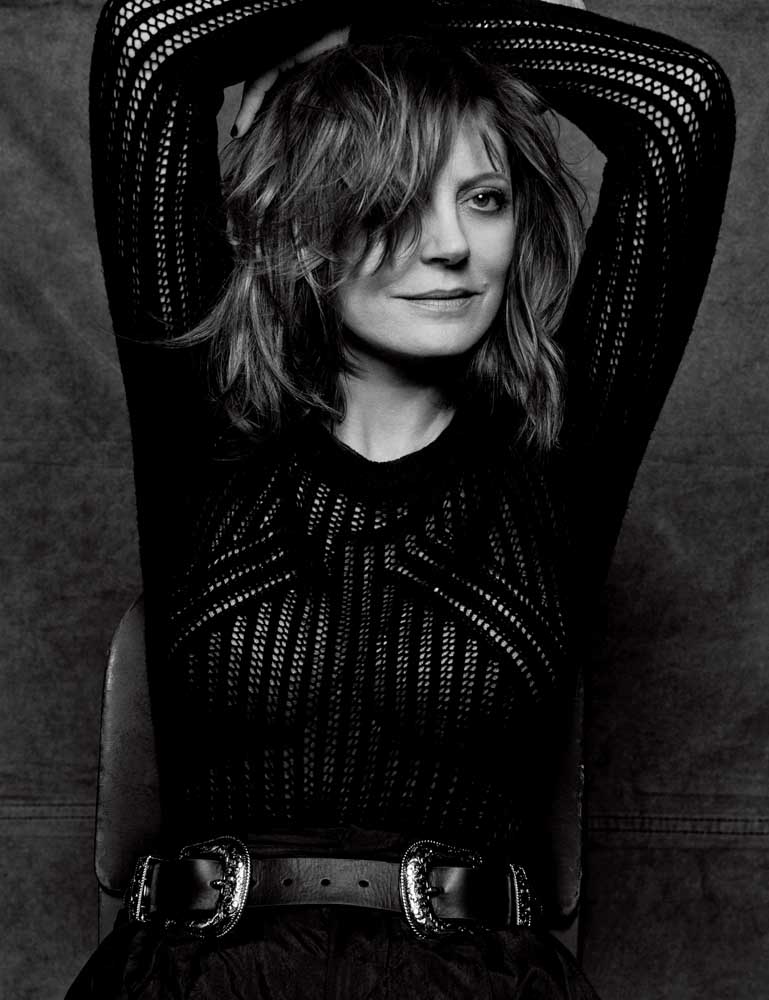

Susan Sarandon

Very often, for me, acting is like loving; it’s using the muscle that you use in loving, in that your heart feels open. SUSAN SARANDON

In many ways, Susan Sarandon has managed to perform the unthinkable two-step in public life. It’s hard to think of another living actress who more confidently and convincingly inhabits her roles without ever seeming to get swallowed up in them. Whether it’s the tough, once-bitten waitress on the run in the seminal road movie Thelma & Louise (1991) or the fearless nun fighting for the dignity of a convicted murderer in Dead Man Walking (1995), Sarandon doesn’t so much disappear like a chameleon into her characters as amp up their humanity, intelligence, resilience, and faults. As a result, her performances do something far more than persuade; they live. Each one is a ticking time bomb of empathy and hope and frustration. And let’s not forget, Sarandon doesn’t only play for awards season. She’s also taken some risky and offbeat detours—The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), The Hunger (1983), The Witches of Eastwick (1987), Igby Goes Down (2002), Arbitrage (2012).

And yet, the 69-year-old New Yorker is the anti-Garbo off the stage and screen. She’s never been one to keep silent about her political and social beliefs. She’s been an extremely vocal champion and liberal activist for decades (against corporate greed and the war in Iraq, for the fundamental rights of women to choose what happens to their own bodies). If you want a public figure that will stick to easy answers and comfortable platitudes, do yourself a huge favor and don’t call Sarandon. This spring, the world gets to see her in her latest role, a starring one. In writer-director Lorene Scafaria’s brilliantly scripted comedy The Meddler, Sarandon plays an overbearing, not-very-deeply-buried live wire of a recently widowed mother who moves to Los Angeles to be closer to her daughter (played by Rose Byrne). Ultimately, it’s more a search for meaning after loss and grief than a light comedy played for laughs. Sarandon has also been busy this season campaigning for Democratic presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders. In fact, she’d just returned from the Nevada caucuses this past February when she got on the phone with her friend, the writer (and everyone’s personal hero) George Saunders. As expected, they went their own way.

SUSAN SARANDON: I can’t believe you had time to do this. You’re my dream guy, and you came through.

GEORGE SAUNDERS: We’ve been trying to sit down and talk for about three years. If this is how we have to do it, so be it. How are you?

SARANDON: I’m good. I left Las Vegas at about 4:30 this morning, and I just got to New York, so I might use more sentences than I usually do to express myself.

SAUNDERS: Well, I got to see The Meddler. I thought your performance was wonderful, so I wanted to start with that. And I should also say, I’m kind of a nerd, so whenever I get a chance to talk to an artist I really admire, I tend to gravitate to process. What I wanted to ask you about was this: your character, Marnie, could, on paper, be an unlikable character, someone who’s a little pushy and maybe a little socially tone-deaf. But you made her so lovable and tender. Really, there wasn’t a frame in the movie where I wasn’t like, “Oh, poor thing.”

SARANDON: She’s based on the director’s mom. A lot of it is their story, and I saw a little teaser after Lorene first asked me to do the movie, of the mom actually doing the opening sequence. I wore almost all of her mom’s clothing—all those animal-print tops and everything. So when I first saw her, I thought, “God, she’s so interesting and so well-meaning—what a character.” So I just suspended my judgment and jumped. And then when I watched the first part of the film, I thought, “My God, she’s annoying, she’s so insane.” [laughs] But the film was such a labor of love. Whenever you’re in a project where the money is really small and the time is very short, people have joined in because they believe in it. So even though we really didn’t have dressing rooms, everybody was working fast and furiously. There wasn’t space to mood-up. I think Rose Byrne was just extraordinary. Talk about a character that could be really unsympathetic at times. She just jumped in these scenes that go from anger to hysteria to crying to laughing and back to anger. I just marveled. And we didn’t have a lot of time to do a number of takes, so I was lucky to have so many great people all around me. You just feel free to do anything, because you know you’re safe.

SAUNDERS: As a fiction writer, one of the things that really spoke to me was the way that the sum total of her personality was made in the juxtaposition of the really annoying moments with the moments where somebody poked at her for being annoying. It was the simultaneity of those two things that made her personhood complete. But you used a phrase a minute ago that I’ve never heard before, but I love. You said, “There wasn’t space to mood-up.” Explain that to me.

SARANDON: That’s one of my little expressions. I never really studied acting so I kind of kiddingly talk about “building your circle” and “mooding up,” because I really didn’t learn any technique. But sometimes when you have to go into something, unless you’re gifted and can just turn it on and off like a jukebox, you find someplace where there’s nothing going on to get yourself into whatever state your character is entering into. But in this instance, we were in the director’s old house that she’d sold to a friend, so there was no place to go, except a room that was filled with all kinds of equipment. So it’s just trying to focus and get yourself in a place where you’re not planning what you’re going to do but just being open to whatever the state is that your character enters with.

SAUNDERS: I’m fascinated with actors, and I’ve never quite understood the process. Right before you’re going to do something, can you rough out for me what your state of mind is? On what basis do you make the thousands of microdecisions with your face and your mind and your body that end up making us feel for somebody like Marnie?

SARANDON: I can’t speak for other people, but for me, it never really worked to think something like, “What Beatle did she like in high school?” or those kinds of elaborate backstories. It never really worked for me to have long arguments about motivation. I think looking at your own life, on- and offscreen, you can motivate anything, or you can delude yourself into anything. Really, for me, it’s important to know who’s pitching and who’s catching—just what that scene is supposed to accomplish in terms of storytelling. That being said, on the day, basically what you’re trying to get yourself into an open place. And if the character is in a state of anxiety or vulnerability, you try to find some touchstone. I don’t think you can plan. I don’t like to plan. Very often, for me, acting is like loving; it’s using the muscle that you use in loving, in that your heart feels open. Physically, you feel open. And so therefore your job is to enter, open, and listen. And see what happens.

SAUNDERS: It sounds like you’re describing a high state of alertness to what is actually happening in that moment.

SARANDON: You have to take away the idea that something you do is right or wrong. I don’t think there’s a right or a wrong; I think there’s an “it works” or “it doesn’t work” for the whole. And that’s why you need a director you trust, so you can just keep throwing out suggestions. And somebody can be the captain of the ship, which allows you to make big mistakes. That’s how you figure out what works and doesn’t work. If you always have to be watching yourself and judging, I don’t think you’re as free. I hesitate to direct even though I feel I contribute a lot on a set. But I feel it’s easier to sit in the backseat and go, “Oh, yeah, let’s go there.” You’re not worried about getting to the destination. But the guy or the woman who has to get you to the destination is worried about a lot of other things, so my job as an actor is to try as many things as possible, be as open as possible, listen, and keep my heart open. That’s the joy when it all comes together and things surprise you, and you find yourself having a moment that you didn’t count on. What I like about The Meddler style of movie is that it’s a fairly lighthearted romantic comedy, but there are hidden moments where something happens that’s unexpected, that hopefully have some kind of emotional resonance that you didn’t see coming. I love when a film does that. That, for me, is what life is like; you’re scooting along, and then all of a sudden somebody comes up to you and says or does something, and you find yourself moved. Other times you’re going into a situation that you think is going to be heartbreaking, and you find yourself really pissed off or laughing at a very serious moment.

the difference between film and theater is like the difference between masturbation and making love . . . in film, you just have to get one moment right; you’re practically by yourself. SUSAN SARANDON

SAUNDERS: One of the inspiring things about your career is that there’s a quality of real fearlessness in it—you seem to be in it for the challenge and the experience. I’m wondering, having done a performance and having given the director a bunch of different things to work with, what happens when you see the final film and it’s not the take you expected or would have chosen? What’s your next move? Because I find that the great artists I’ve met are people who are so playfully invested in their process that, even if it doesn’t come out the way they like, they still power through and even take energy from it. Does that ever happen to you while watching the final film?

SARANDON: Yeah, absolutely it happens. With the most interesting directors, the cast comes together to make something magical that nobody counted on. So I think you have to be ready to switch gears and go with the team as a director, as opposed to superimposing your own strict idea of the story. There are very few directors that can micromanage and still come out with something that’s living and breathing on a page. Wes Anderson is one of those where, if he has a very strong cast, he can direct the minutia of that story and still manage to have something that lives and breathes. Because sometimes what happens is that, when you micromanage actors and moments, it just doesn’t quite live. The directors I consider really great have the ability to recognize when something’s going in an unexpected direction and see it as a bonus and be able to go with it, as opposed to locking down what they thought was going to happen.

SAUNDERS: There’s a great Gerald Stern quote, where he said, “If you start out to write a poem about two dogs fucking, and you write a poem about two dogs fucking, then you’ve written a poem about two dogs fucking.” So the whole idea is you’re trying to start with a plan and then have the thing talk back to you in a way that makes you disrupt the plan.

SARANDON: What happens when you write? You don’t have everything figured out, do you?

SAUNDERS: No, I have nothing. My model is I have nothing figured out, and I’m starting with some little nugget and hoping that it will talk back to me enough to let it grow. But what I find fascinating about what you do is this: It’s easy to enact that model of openness when you’re by yourself and you have infinite time. But when you’re working with a team, and it’s competing visions and strong-minded people, I imagine that sort of ad hoc group compromise must be really challenging. It’s one thing to be a perfectionist when you’re alone, but when you’re trying to make it work in an ensemble that’s a whole different deal.

SARANDON: It can be very heartbreaking. Sometimes it’s ruined when suddenly there’s really cheesy music or when they over-score it or they cut around you because somebody else isn’t working. Or the way they edit the movie ends up turning it into something more marketable. It’s a miracle when something actually turns out well because there are so many ways for it to go wrong. That’s why I learned many years ago to focus on the process and have as much fun as I can in the process. Because then you send it off to school and there’s no telling who it’s going to fuck and end up with at the end of the day. [Saunders laughs] Sometimes they don’t even let it go; they bury it. There have been a few little films I’d done like that that the studio just decided not to do much with, films like Anywhere but Here [1999] or Jeff, Who Lives at Home [2012]. Thank God people find them later and love them. I’m always really drawn to people who have seen these strange little films. It’s nice when that happens. But very often it is heartbreaking, so you just can never count on a formula, on a movie that you think is going to be a big hit, and that’s why you do it. You have to choose each one for what you think you’ll learn and the fun you’ll have. And maybe the cool people that you work with or a character that you’re going to be able to explore … You just keep your fingers crossed.

SAUNDERS: When I was watching you, in this film and in so many of your other ones, one thing that hit me is that what makes you such an important actress is some almost indefinable thing that I think has to do with your innate intelligence. So in other words, some kind of subliminal human thing, where we see a highly activated, intelligent person, and our eye is drawn to her. So I want to ask you this: If we could look back at you as, say, a 10-year-old and get inside your mind, into your fantasy life and your wishes, what would we see there that we could now go, “Oh, yeah, that was the beginning of an artistic life.”

SARANDON: That’s an interesting question, and I don’t think I’ve ever been asked that before.

SAUNDERS: Boom! Give me a talk show.

SARANDON: Boom! I was very withdrawn and definitely played with dolls well into eighth grade. But I was the oldest of nine, and that grounded me in a way that I don’t think I would have been grounded otherwise. So I was able to—or forced to—function practically. But I think, by nature, I was someone who lived in my head, in my imagination. I wrote what I thought were plays, but probably would have been more like movies. It never occurred to me to act. I wasn’t that outgoing, really. But being a Catholic, I was drawn to the mystery of the Latin and the smoke and the mirrors and all of that. That part of my disposition definitely did lend itself to finding my way to the back door of some artistic pursuit.

It’s a miracle when something actually turns out well because there are so many ways for it to go wrong. That’s why I learned many years ago to focus on the process and have as much fun as I can in the process. SUSAN SARANDON

SAUNDERS: I was raised Catholic, too, and I think that’s so right; what I took from that was a sense of theater and drama, and also the idea that there were truths that couldn’t actually be uttered directly but really had to be reached through ritual. You come out of those Masses so moved, and you’re like, “Why did that happen?” And the truth of it is that it happened through an hour of highly enacted ritual.

SARANDON: Well, trans-substantiation.

SAUNDERS: Oh, what a word!

SARANDON: From the very beginning, that sets you off in a certain direction. Later the church let me down. I always had a problem with original sin; I always had a problem with the exclusivity of the church and a lot of the things that the nuns taught me. So by the time I went to the Catholic University of America, which was the time the priests were all leaving with the nuns, the more I studied about the Bible and how it came about, the more I lost my faith. Because it didn’t seem to have relevance, except in Central America or South America, countries where the church was connected to the fight of the people for economic justice. That’s why it was so interesting to find myself back with Sister Helen [in Dead Man Walking], this new breed of nuns who were making a difference in the community. Because once we got past the smell of the church and the ritual of the church and all of that, and actually got into the doctrine … When I grew up in the church, we were praying because the Communists were going to come over and hang you upside down on a cross, and I so wanted to be a good person, and I had these rosary beads that I would sleep with every night, and I just wanted the blessed Virgin to be on my side. Then one night I looked down and my rosary beads were glowing. And I realized that I did not want to see the blessed Virgin—I was terrified.

SAUNDERS: They were glowing?

SARANDON: They were glowing because, unbeknownst to me, my aunt had given me these rosary beads that were glow-in-the-dark. [Saunders laughs] So all of a sudden I look down and they’re glowing, and I’m looking toward the door and thinking, “Oh, my God, I don’t want anything to come though here. I’m not worthy, I’m not ready.” I didn’t want to be one of those kids who sees Our Lady of Fatima.

SAUNDERS: I was, not an altar boy, but a reader of the Epistle, and I walked in on a nun and a priest furiously French kissing when I was in seventh grade. I walked in, saw it, and went, “No way,” backed out, composed myself, and went back in, and it was still going on. And the experience of seeing that was actually very deep. Because it didn’t cause me to lose my faith, but suddenly you realize, “Well, they’re just people.”

SARANDON: I don’t know where that ranks. Is that worse or not as bad as seeing your parents have sex?

SAUNDERS: [laughs] But this Catholic thing, I think what it does is it makes a place for mystery in a person. And even when the faith goes away, there’s that space where you crave something bigger than yourself. For me, that’s kind of where art came in, after that.

SARANDON: Right. Well, there are a lot of Catholics in this business. I don’t know about other disciplines. But there are definitely a lot of Catholics—lapsed Catholics.

SAUNDERS: Only lapsed. Let me kind of sidebar that. Was there a moment when the young Susan went, “I want to act”? Did the light bulb come on all at once? Or was it kind of gradual?

SARANDON: It never came on. What happened was so strange. I did study drama at Catholic U, but the undergraduates weren’t put in productions, really, except as extras, and it wasn’t a hands-on kind of thing at all. I couldn’t afford to go to another college. And my grandparents lived in D.C., so I was able to live with them, and that’s how I was able to afford it at all. I worked at the switchboard in the drama department, which is probably where I saw the most drama. So what happened was, to get out of my grandparents’ house, I got married to Chris Sarandon, who was a graduate student, and he knew everything at that point, I thought, because he was older. He introduced me to poetry and black-and-white movies. Anyway, I married him my senior year, and after I graduated, he went to the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven, and I tagged along and was doing some local modeling and commercials and things like that. A woman named Jane Oliver, who handled Sylvester Stallone, saw Chris at the theater and asked him to come in and audition. We went in and auditioned—he needed someone to read with him. I read with him, and she said, “Well, why don’t both of you come back in the fall.” Chris had a job in summer stock. So I went off, the little wife, to summer stock. And then in the fall, when we came back, she set me up in the first week we were in New York with a film called Joe [1970]. Chris got cast in a Broadway show, and I went up for this movie that John Avildsen was directing. It was his first real movie; he wasn’t even in the Directors Guild, so he wasn’t officially directing it, and it was the first movie that this company was making that wasn’t a pornographic movie. They called me in and asked me to do an improvisation. I asked them what that was, and they explained it. People who teach acting hate this story, but this is actually what happened. I did the improv and they said, “Okay, wait here.” And they came back and said, “We’d like you to do this film.” Then I just kept getting things. I did Joe and then I got a few other things and got on a soap opera, again, not knowing what I was doing. But that was a fantastic way to learn, because it was kind of live and with cameras. It was in the moment. Things just kept going like that for eight, nine, ten years. And then finally I just had to admit—I guess this is what I do. That’s really the way it happened. And I think it made it easier for me. I always saw it as a means to an end and not an end in itself, because it dealt with so much self-examination. I also had school debt I had to pay off. Sometimes I would do commercials to get me through. And so I kept bumping along like that and learning different things. I knew I wanted to get out on my own. I was just super-curious, and I was a good listener. And that got me through.

SAUNDERS: Along that path, are there moments you can remember where your understanding of your craft leapt up because of something you encountered during a project, or because of something someone told you?

SARANDON: There’s that connection where you’re really with somebody and you’re listening to them and something happens that is surprising and it keeps you hooked. It was like that for me, and then I’d see the results and want it to be better or braver. And I never felt that I had completely conquered the task. So that kept me coming back. I’d think, “Oh, I was on to something in that moment, but why didn’t I just really do it? I chickened out.” Or, “God, that was right, but it wasn’t clear enough. If only I had trusted it.” Then I learned to say, “What’s your framing?” So much really depends on the camera crew. And I’d have conversations with the camera crew about what was going on in the scene, so that they were prepared to shoot it. I love the fact that when you work, you create this tribe. You create this situation where you are so dependent on each other. That’s especially true for film. In theater, the actor has much more say, much more control, for better or worse. I always think that the difference between film and theater is like the difference between masturbation and making love. Because, in film, you just have to get one moment right; you’re practically by yourself. And in theater, you actually have to have a relationship with the audience. So for that reason, theater for me is terrifying but much more rewarding, because you know what they’re seeing. Film is all little bits and pieces. And you can do an amazing job, but if the camera isn’t getting it, it doesn’t work. And then other times when you feel you really weren’t present, and then you see it and somehow it works. So there’s a mystery, there’s a strange collaboration that takes place with everybody.

acting is kind of a forced compassion . . . You can feel and do things that you never thought yourself capable of. And so it stops you from being super-judgmental. susan sarandon

SAUNDERS: That feeling of coming to part after part and feeling the little flare-ups of really being in it must be kind of addictive, and it must flow into the rest of your life.

SARANDON: Absolutely. What makes that connection addictive is that, when you know it’s working, something real happens. Even if it’s painful. Although I remember Anthony Perkins saying, “Real is not necessarily interesting.” So real is not enough. But what happens as an actor is that you’re really trained to listen and to be open and have empathy. It’s such a natural consequence that you end up being more political. You can empathize with the mother whose kids are going to be sent to Iraq, or you can emphasize with the mother who is losing their child to a disease. How could you not then be active? So you’re automatically drawn to that aspect in the rest of your life. Most of the people I really admire bring that attitude toward their life. For example, I was reading that commencement speech you gave at Syracuse. And I could see how the memories that you mention from the seventh grade also play out, thematically, in your short stories. There’s that sensitivity and observation and recall you have, even in the midst of the weird-ass situations you come up with, that people are complicated and yet these moments are so moving. But not sentimental. That’s one of the things I tell people whenever I’m handing out your books. Which I do quite often, by the way.

SAUNDERS: Thank you.

SARANDON: I should get a percentage.

SAUNDERS: I was wondering about that little bump in sales.

SARANDON: That’s what I love about your writing. You’re clearly somebody who has been picking up and learning as you go along. And it reminds me a lot of my old friend Kurt Vonnegut.

SAUNDERS: I wanted to ask you about him. But first, before I forget, let me ask you a parenthetical: You talked about the way that the empathy that you feel for a character, that’s almost like compassion training wheels, and you take it out into your life. Could you play somebody for whom you didn’t feel any natural empathy? For example, could you play Ann Coulter or someone else that you really didn’t agree with?

SARANDON: That’s a good question. I guess it would have to be a character that I’ve not done before. I have played horrible mothers. I’ve played a Republican prosecutor wanting to run for the Senate who’s doing terrible things. But I think you have to look at how it’s written, and whether or not there’s something in that person to connect with. Because, really, acting is kind of a forced compassion, where you learn that given certain circumstances, you can feel and do things that you never thought yourself capable of. And so it stops you from being super-judgmental. But at the same time, I think you have to ask yourself, what is the point of the script? What is the script selling? Because all scripts are political, every story is political. It either challenges or reinforces some schism or stereotype. So what is the project going to say at the end of the day? What does it tell you about the world, or what does it challenge in terms of your world? And I don’t mean that it has to be Dead Man Walking, but even with The Nutty Professor [1996], it’s amazing that you’re rooting for her to get the fat guy. That was an amazing hour and a half that they did with that movie. So I don’t mean that it has to be obvious about an issue. But you’ve got to take responsibility for what you put out there. So I would have to like her for some reason—even if it’s her blind delusion—or else I wouldn’t want to play her. Because you have to live with them for a long time.

SAUNDERS: The question comes to life for me when I consider writing about certain people in the world right now who—granted, they’re cornered or they grew up a certain way or whatever—but people (murderers, war criminals) who do really reprehensible things, and in that particular moment they really aren’t redeemable. And I wonder, is there a place in art for that character? I’ve had that situation where I start writing somebody really miserable, and in order to make the story come alive, I have to give them a vote of confidence, make him vulnerable or wounded. But in real life, you often meet people who, in that particular moment, actually shouldn’t get a vote of confidence. I often wonder if there are certain areas of real life that are roped off, with a sign saying, “Art, don’t come in here.” But that’s maybe a deeper question …

SARANDON: That’s a really good question. You know, when Alan Rickman, a dear friend of mine, played villains, he always made it complicated. He didn’t redeem what they did, but he made you feel that it was hard for them to be so horrible.

SAUNDERS: Right. There was a cost.

SARANDON: Because it gives you pause. I think where you get into trouble—for instance the mixing of sex and violence—is when you’re telling an audience that this horrible thing is enjoyable. The suffering just gets out of hand too much. It becomes pornographic.

SAUNDERS: Well, it’s inaccurate, isn’t it? The idea that those kind of behaviors would be cost-free is kind of delusional. I heard this Zen teacher one time talking about abortion, and he was saying the way that abortion makes bad karma is any time the person involved pretends that there’s not a cost to the choice, one way or the other; whether you get it or don’t get it, there’s a cost. That’s just basic responsibility, to admit that there’s a cost. And the bad karma is when you pretend that the thing is free.

SARANDON: It’s interesting that you bring that up. Because when I got the script for Thelma & Louise, when I met with the director, Ridley Scott, I said, “I don’t want to do a revenge film. I’m not interested in doing that moment in the script after they shoot the truck, where it says they jump up and down and they’re real happy about it. And before she kills the guy, she takes a stance like a police officer.” I said, “That doesn’t really interest me, to be Charles Bronson. What would be interesting to me is that there is a price.” She understands when she kills that guy, and she kills him not as an execution, in my interpretation, but just trying to shut him up, and her rape from the past takes over. Then she’s on the rest of this journey knowing that she’s going to have to pay. So I said to him, “If, at the end, you redeem her, then I don’t know where I’m going. So let’s make the drive a week or five days, have her not get much sleep, where going off the cliff seems like a good idea. It can’t be as long as a month, because then you have time to think about it.” And when we were shooting, I added some lines. I think what’s really motivating her, what’s pushing her, is not revenge, but it’s trying to understand why men would think women would want this kind of behavior. And so we added some lines. That was the through-line that I took instead of revenge. Because I think that’s what made it different, instead of a shoot-’em-up cowboy film. It just didn’t interest me the other way.

SAUNDERS: The great American denial riff is that you can do whatever you like and you always triumph at the end. The world is saying no, you can do what you like, but there are consequences. And maturity is to be able to turn to the consequences and accept them.

SARANDON: Well, in terms of our foreign policy, that’s where we made a mistake after 9/11. Everyone’s going, “Why, why, why,” and there wasn’t any investigation or learning from any of what we had been doing up to that time that had set us up. Not that we deserved it, but that [our actions] led to consequences. 9/11 just seemed to come out of the blue. And there were people asking questions, but then there were no answers. At some point, it just turned into, “We’ve got to do what we’ve got to do.” And I think those are the moments when you grow, when you get the opportunity to try to figure out, exactly as you said, what price are you paying, and if it’s worth that price.

SAUNDERS: It seems like, in our discourse, there’s a real discomfort with any kind of not-knowing or ambiguity. For example, we don’t really know why we kill each other with guns so much; it’s actually a really hard question to answer. But that’s a very scary space to go into. Usually, we just rush in with a too-easy answer, which doesn’t convince or satisfy. So I would love to see a candidate who would just say, “I don’t fucking know why, but let’s try to find out; we have the resources.” Let me go back and just ask you, can you tell me how you met Kurt Vonnegut, and what your impressions were of him?

SARANDON: I came to New York the same time that his daughter Edith did. We were friends with Jonathan Demme. We were all down on the West Side of New York, and I think I met Kurt through Edie. And then I was lucky to do Who Am I This Time? [1982], which was an adaptation of his short story that Jonathan Demme directed with Chris Walken and I, and that really cemented the friendship. And even when Edith moved out of the city, I kept in touch with Kurt. And also politically there were a number of times when we found ourselves in the same place trying to point out what was going on.

SAUNDERS: What was he like, personally?

SARANDON: He wasn’t a chatty guy, but when he spoke, it was always clear and very funny, in the way that he wrote, in a very specific kind of combination of word groupings and expressions that lived somewhere else; he felt kind of like small town on your porch, but yet they were perfect little pearls and gems. I’ve read some of his letters from when he was young. He was a prisoner of war, and even when he was in his early twenties, there were things mentioned that showed up in his novels. One of the sweetest things in those letters was him wanting to be a writer but doubting himself, not having confidence in himself. But still, his powers of observation were so strong. He had a particular way of framing things. As I’ve said, I’ve just come back from Vegas, and I was in on the caucus process. It’s insane. What a mess. And also with these particular candidates who are running, so many times I said, “I just wish Kurt were alive.” This is like something he would be writing. This is just crazy stuff. I would love to hear his take on it.

SAUNDERS: Bernie didn’t win in Nevada.

SARANDON: No. I mean, it was very, very close. But it was so chaotic. It was kind of discouraging, that whole process. But considering the difference in the money and how far down he was in the polls early on, I think he doesn’t consider it a failure, from what I can tell. I think they want me in Massachusetts and in Maine, which is fun.

SAUNDERS: He’s wonderful.

SARANDON: He’s great. It’s a very exciting time in the history of this country, to even see people responding to a different way of doing business and really wanting to make a change.

GEORGE SAUNDERS IS THE AUTHOR OF EIGHT BOOKS, INCLUDING THE SHORT STORY COLLECTIONS IN PERSUASION NATION AND TENTH OF DECEMBER. HIS NOVEL LINCOLN IN THE BARDO WILL BE OUT IN 2017.