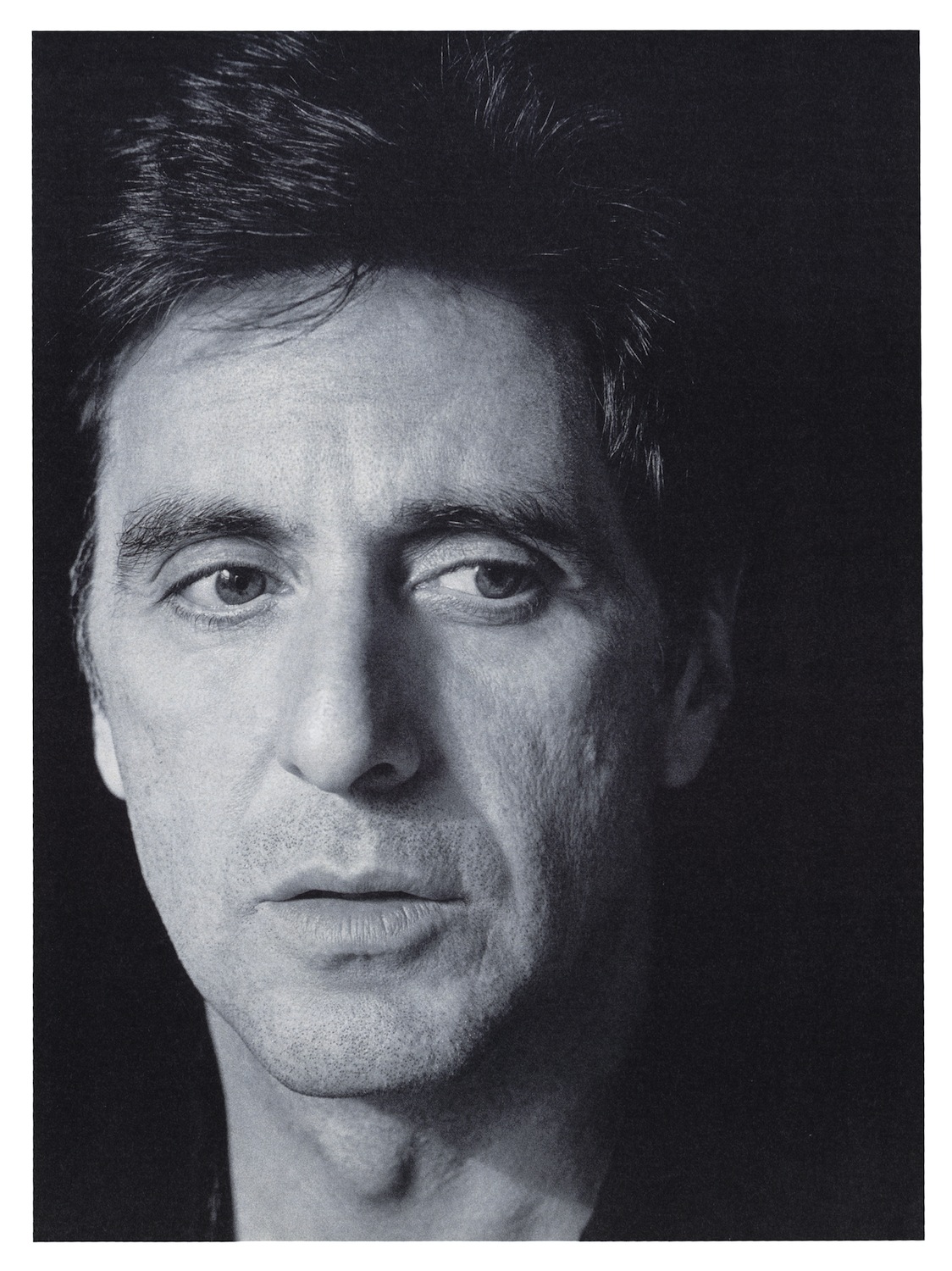

New Again: Al Pacino

Today, we’d like to wish a very happy 72nd birthday to one of the titans of American cinema, Al Pacino, who has perfected his own masterful blend of intensity, coolness, and control on the stage and screen for over four decades.

A product of Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio, Pacino lurched onto the screen with a turn as a heroin addict in 1971’s The Panic in Needle Park, following it up with a series of films that defined the cinema of the ’70s (The Godfather; Dog Day Afternoon). Best known for playing both sides of the law (Scarface‘s louche and lawless Tony Montana; undercover do-gooder cop Frank Serpico), in recent years Pacino has diversified, taking on roles such as Dr. Jack Kevorkian (You Don’t Know Jack), Shylock in a Broadway run of The Merchant of Venice, and murderous pop pioneer, Phil Spector, in an upcoming biopic. (We shall dutifully ignore his appearance in 2003’s widely panned Jennifer Lopez/Ben Affleck flop, Gigli.)

Pacino covered our February 1991 issue. In the interview (reprinted below), he chats with artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel on the occasion of the release of The Godfather, Part III, with which Pacino concludes over two decades of inhabiting perhaps his most famed cinematic role, Michael Corleone. Schnabel, already a devoted Pacino fan (and friend), aims to figure out exactly “What makes Al tick?” Here, Pacino talks the psychology of gangster films, the unwavering power of Brando, and the curious magnetic nature of the theater.

Al Pacino

by Julian Schnabel

Al Pacino is one of America’s truly great actors. His performances in Dog Day Afternoon, Scarface, and the Godfather films have made him an American institution. He has given a relentless emotionality to the characters he has portrayed, to the extent that I am surprised he can still stand at the end of the day. He has inspired a generation of young actors. He is Tony Montana. He is Michael Corleone. This interview is not about The Godfather Part III but is with a man who is an integral part of the familial consciousness of this country.

The first time I met Al Pacino was about four years ago. Diane Keaton knew I wanted to meet him. She was familiar with my Tony Montana impersonation. I remember her telling me, at my house before going to dinner, “Whatever you do, don’t do your Tony Montana routine.” We were in an Italian restaurant on Tenth Street, and the din of the glasses, plates, waiters, and the crowd brought me back to that scene in Scarface when a disgusted Tony Montana gives his opinion of a restaurant’s dinner guests. Before I knew is, the words popped out: “So, Manny, eez theez what it’s all about? Eez theez what I worked so hard for? Is this it? Is this what it’s about . . .?” To which Al said, with a smile on his face, “Then what did he say?”

AL PACINO: Is that coffee fresh enough?

JULIAN SCHNABEL: Is it mine? I don’t care if it’s fresh or not.

PACINO: Pour some of the coffee out of the other cup right there.

SCHNABEL: That reminds me of The Godfather, when Clemenza is showing you how he makes his spaghetti sauce and he says, “You throw in your meatballs, you throw in your sausage, a pinch of sugar—and that’s my trick.”

PACINO: A little sugar’s the Sicilian way.

SCHNABEL: Where are you from originally?

PACINO: I was born in Manhattan. I was raised in East Harlem in my early years, and then we moved to the South Bronx.

SCHNABEL: What did your dad do?

PACINO: My dad was in the army. World War II. He got his college education from the army. After World War II he became an insurance salesman. Really, I didn’t know my dad very well. He and my mother split up after the war. I was raised by my maternal grandmother and grandfather, and by my mother. It’s so funny to talk about all this. You don’t know these things yet.

SCHNABEL: The only thing I know is what I’ve seen on the screen.

PACINO: But there’s a difference.

SCHNABEL: Of course. That’s what we’re trying to find out here. What makes Al tick? So why do you do it?

PACINO: It’s necessary to do it. Why I am here, and why I started to do this, is because of the kinds of things that were around when I was at an age when they impressed me. I was impressed by the experimental theater of the Living Theatre in the early ‘60’s, and by the Open Theatre, and I was impressed by early Circle in the Square days. These kinds of things were motivators—as was the café-theater era, when you’d go to a coffeehouse anywhere in the Village, and for the price of a cappuccino and a piece of pastry you could see some wonderful pieces being played by actors who passed hats around for whatever they could get for their meal that day. I became part of those troupes that traveled. I did children’s theater and that kind of thing for whatever it was we could get.

SCHNABEL: I made a couple of drawings on the beach in Sheepshead Bay one time when I didn’t have any money and I wanted to get a knish. There were three little girls sitting on the beach. I said, “Listen, I’ll do your portraits. For twenty-five cents apiece I’ll put all three of you into a drawing.” Two of the little girls likes the drawing and gave me their quarters, but the third didn’t like the way she looked, so she didn’t want to pay up. I sold the thing for fifty cents.

PACINO: The difference between the actor and the painter is that the actor would buy somebody a knish in order to have them watch him act. “See, listen. I’ll buy you a bagel if you let me do this monologue.” [chuckles]

SCHNABEL: How about a coffee malted and a bagel? My dad was pissed at me for selling a drawing for fifty cents for a knish.

PACINO: You’ve got to eat. When I was younger, I would go to auditions to have the opportunity to audition, which would mean another chance to get up there and try out my stuff, or try out what I learned and see how it worked with an audience, because where are you gonna get an audience? Sometimes the only way you can get an audience is at an audition. I’d never expect to get the role, of course. I don’t think actors should ever expect to get a role, because the disappointment is too great. You’ve got to think of things as an opportunity. An audition’s an opportunity to have an audience.

SCHNABEL: Now that you’ve had a few parts, I’m sure auditioning is less satisfying. Auditioning is just a bite of the knish.

PACINO: As you get older, auditioning becomes harrowing and difficult, but at that time it got me through many a week. We need the part—we need the play, we need the movie. It’s hard to call what part is gonna do it. So the only way you can know is if you do many parts. You’re gonna find something that you feel you can play. And some of the parts are not going to work, and in movie parlance, that’s a disaster. But sometimes the only way for actors to find that out is to experience playing it. You can’t know it sometimes just by reading it.

SCHNABEL: Yes—you have to make your own mistakes. But let’s talk about the magic when it works. Like you playing Tony Montana in Scarface. When you’re willing to get out there and go so far, get so involved in a role, doesn’t it just wipe an actor out?

PACINO: Well, yes. When you play a role like that you need to find balance in your life. I was fortunate, because I had fallen in love. I had something to go to. It literally saved my life. I don’t know what would have happened to me if I hadn’t fallen in love at that time. Was it coincidence? I don’t know. Maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t. Maybe I thought, it’s a good time to fall in love, you know? Isn’t it odd?

SCHNABEL: [Not wanting to be a snoop, I change the subject.] Talking about coincidence and love, let’s just cut to the chase. What about hate and violence, and the fact that it’s no coincidence that so many gangster movies came out this season: GoodFellas, State of Grace, King of New York, Miller’s Crossing, and, obviously, the latest part of the godfather of them all, The Godfather, Part III?

PACINO: I think there have always been gangster pictures. Bertolt Brecht took a lot of his inspiration from early gangster movies. The original Scarface was a ’30s gangster picture. That’s why I did it, because I saw that picture.

SCHNABEL: But wait a minute. There’s a level of violence in these films these days that scares the shit out of me. There’s a line in Godfather II that I’d like to quote: “If history has taught us anything, it says you can kill anybody.” And that approach to life is what marks our atmosphere. By the end of King of New York everybody dies a violent death. I mean, why is everybody so fascinated with gangsters?

PACINO: Why ask me? [chuckles]

SCHNABEL: You’re the Godfathers’ Michael Corleone, no? You’re Scarface‘s Tony Montana.

PACINO: There’s something fablelike about Tony Montana. He’s like Icarus flying close to the sun, just going a little closer and closer, knowing as soon as he gets close enough those wings are going to get burned—he’s gonna soar right down. That’s what attracted me to that character. The whole idea of how he flirts with the sun. When were people ever not fascinated by the gangster world, that underworld, that world that’s illicit? It’s always fascinating to see how and why people go to the wrong side. The idea of somebody who’s flirting with the big D, you know. It just fascinates people. It fascinated me to do it. What’s becoming more and more fascinating is people who abide by the law. That’s becoming more infrequent, and therefore maybe that’ll become trendy. Maybe they’ll start making movies about people who really obey the law.

SCHNABEL: And why did you start wanting to be in movies?

PACINO: It started for me when I was very young. I mean, really young. I wasn’t let out much. I was kept in. And while I was home I found myself repeating the roles from the movies I saw with my mother. Sometimes she’d take me to the movies when she came home from work. That was our date. So I was sort of weaned on ’40s films. The next day, left home alone in the house with my grandmother, seemed endless, playing alone. Pretty soon I started playing the parts of the movie I’d seen the night before. That’s how it started. Also, I had two deaf aunts, whom I spent almost a year with at a very young age. That probably is where some of the stuff started—in order to communicate, you know? These are the seeds, but it wasn’t until I got older that I understood that acting was something I really would do.

SCHNABEL: Is it because it took you into other lives?

PACINO: You ought to be able to get away from whatever this is—whatever this dream is that we’re in right now—and go into another dream. You know, when you’re reading some of the great plays, when you do what I call “taking up with a writer,” something happens. If I were a musician, I’d plan to be involved for the next six months with Mozart, so I’d be playing a lot of Mozart. After six months of doing that, you come out and you’ve been with Mozart. You’ve been touched. The same thing goes with the writers—either today’s writers or writers from the past—who are plugged into some kind of thing. You get affected by it. When I was young I fell in love with what happened—with that kind of world. Once I fell in love with that, that was it. It no longer mattered whether I made any money at it or had any position in it. I hope I have remained a little bit in love with it.

SCHNABEL: A little? A lot, I’d say.

PACINO: Yes. I—I don’t know. That’s why I like to go back to the things that I did originally.

SCHNABEL: You mean theater?

PACINO: Well, I like the theater, because theater is where I started. I’ve now come to a point where I understand movies like the way I understand theater. It’s a relationship vis-à-vis me. It had a lot to do with making my own picture [The Local Stigmatic] and being in contact with film that way—being able to touch it and understand it, and recognize the variants that go into a movie, the different jobs, the people who do the sets, those who photograph, and those who do the sound work. Theater for me at one point was a lifestyle, too. A well-known movie actor once asked me why he can’t get back behind it, and I said, “Possibly because it’s the lifestyle that is so different. You know, you’re not getting up at six or seven in the morning. You’re going to sleep at six or seven.” I’ve always been in the theater. I’ve always gone to it. That’s been my way to cope. Early on in my career, I remember running—fleeing—to the theater as a way of coping with all the meshugaas that was going on for me. At that age it was all very alien—”strange and unnatural,” as Hamlet says. Hiding in the theater had its downside, but it was also a wise choice. Somehow, I get a solace there. It’s on those planks that I feel connected to a whole. To my whole past, my whole raison d’être, as they say. When I’m flustered or confused, I will go to the theater. Whatever I wind up doing is besides the point. The fact is that I am in that space, in that particular reality, dealing with those kinds of things—the play, the playwright, the director, the other actors. The literal, basic thing of the stage is really like a magnet. It brings me back [claps for emphasis] to earth.

SCHNABEL: And to your beginnings.

PACINO: There’s a great line from Orphans: “Little boy, you need encouragement.” I was just thinking the other day about something I had never thought of. I realized that my mother gave me encouragement. When it comes right down to it, it was my mother who said, “I like what you did! That thing you did the other day? I like that!”

SCHNABEL: I didn’t know anything about your past. Maybe I’m not reading enough, but I suspect it’s because you’re a very, very private guy. You’re gun-shy about public places.

PACINO: Playing a character is an illusion, and I feel that when you know too much about a person, possibly part of that illusion is disrupted. I don’t know how right I am, frankly. But it’s been a thing with me. Sometimes, you know, we get into habits, and we don’t even know why anymore, but we’re in a habit. This is what you try to do in acting too. When you’re acting in a scene, in the theater, say, you do something and you know it’s right. You’re lucky enough to get a moment. And then the next night you try to repeat it. Then pretty soon all you’re going after many, many nights is repeating the moment, and it’s gone bad. You’ve forgotten about the source, how you got there, what made that moment possible. Maybe I got into the habit of not stepping out because it worked for me before. I enjoy the company of people. Sometimes I’m separated from them by my work. I go off into work, and that can last a long time—especially in the movies, when you’re out of touch for seven or eight months. And you come back and the rhythms have changed, people are no longer together, and things like that. You find out that a couple you used to go out with are now divorced or something. Just the other night I thought, Are there any watering holes anymore? Where do people go? You have such a city as this—such a cosmopolitan city as New York—where you know there’s a world and an underworld going on besides the one you are seeing out here. You know, when they took away the Automats and the cafeterias in New York, I felt very left out. Because they were a part of my life. I hung out in cafeterias and had these sort of “nocturnal confabulations.”

SCHNABEL: Wandering around at night in New York—not only having confabulations, but confrontations? I mean, you’re not a large person.

PACINO: In size?

SCHNABEL: Yeah, in size.

PACINO: A much less easy target, then.

SCHNABEL: In Scarface you confronted huge bouncers in the bathroom of a nightclub, and they got out of your way because you were a maniac. And in so many films—whether it’s Serpico, Sea of Love, and so on, you’re cast a tough guy. Look at you. You’re so wired; there’s this intensity that translates into size. You know, when look at a guy like Brando, he’s also not tall in stature.

PACINO: But he’s wide. He’s like you are. Massive shoulders—he was a football player.

SCHNABEL: As long as you fill up the screen, I guess it really doesn’t matter if you do it vertically or horizontally. Brando’s great. He’s so great.

PACINO: Yes. Brando’s a giant on every level. When he acts it’s as if he landed from another planet. A planet where they produce great actors. The whole perception of acting in this country—I think a lot of it was influenced by him.

SCHNABEL: For a young actor, the possibility of playing his son in The Godfather must have seemed unreal. Isn’t that a part that every single young actor would have chopped off a limb for? But your involvement with The Godfather has been even more than a privilege to work with this great man. You own role has become mythic. Now, with Godfather III, you’re the only son left. What a life’s work this job opportunity turned out to be. For twenty years you’ve been developing and living with character, Michael Corleone.

PACINO: Yes. The truth is, the guy is much older when we pick him up in this picture, and I am too. The saga was a long, complicated journey for Francis [Coppola] and Mario Puzo. They made it together. And for me they came up with a character that is credible in the sense that he seems to be a continuation of Michael, only he’s different in a way that seems organic. It was all very interesting to think about what happened in the ensuing years, to speculate on what could have happened to a person like this. They didn’t lose the continuity. He’s different, but as different as a person like that would be in order to survive the kinds of things that happened to him. And I don’t mean because somebody was gonna knock him off. Just to live with what he’s—

SCHNABEL: Done.

PACINO: I mean, this is a person who had another destiny—at least he thought he did—who had another way to go, who had a desire to do something else and was taken off his course and put on another course. The moment when he made the decision to go in that direction has been the thing that he has dealt with his entire life. Talk about being responsible for your actions. That’s one of the themes of this third movie. It’s what’s interesting to go into for anyone.

SCHNABEL: Do you think that he is still a sympathetic character in Part III? In the first part he had this allegiance to his father. He became strong to keep the family together. He came through like a good son would, and he saved his father’s life. He did what he had to do when he knocked off Sollozzo, his father’s enemy. And then later, when they were sitting together, he said, “We’ll get there, Pop,” and there was this incredible sense of justification for what he was doing. But since those early days, when it was circumstances that forced him to join “the family” in the course of Godfather and Godfather II, he’s become the thing he feared: the sword. He’s even killed his own brother. Do you think the audience is still rooting for him?

PACINO: There was a controversy at the time. I only heard about it later on. The question was, if Michael kills his own brother, is the audience ever going to accept him? And we don’t know if they accept him.

SCHNABEL: Why do you kill Fredo?

PACINO: I guess there are reasons why Michael did it. If I go back and think about it now, they have something to do with maintaining a certain sanity, because if Fredo was allowed to live, then that would have discredited everything that happened before. That’s the insanity. I think that’s where Francis is talking about a kind of power syndrome and the dream. The American Dream, and holding on to it, because it’s a structure. It has definite rules. It you break the rules, then the whole thing collapses.

SCHNABEL: It’s great when his sister comes to him and says, “I want to book passage on the Queen.” And he says, “So why do you come to me? Why don’t you go to a travel agent?”

PACINO: This is someone who had to put on blinders to keep moving. I think Part III might be about letting in more light and seeing where that goes. But he is still a very tricky guy, a kind of enigma to me.

SCHNABEL: Right. I was going to say to himself, even.

PACINO: Enigma’s the word that stuck when I read the book for the first time, twentysome years ago. I thought, This is difficult to play, because who is this guy? And how to get at that? That was what the struggle was for me when I was younger. Somehow through the years I just think I might understand him a little more.

SCHNABEL: I’ve seen Godfather II fifty times, probably. Like somebody listens to the radio, I watch Godfather II. [Pacino chuckles] I can’t get over that moment when you ask Hyman Roth [Lee Strasberg], “Who killed Frankie Pentangeli?” And Roth answers, “The Rosato brothers.” Then again you say, “Who gave the order? I know I didn’t.” And Roth tells that story: “There was a kid I knew. We did our first work together. . . . And as much as anybody, I loved him. He had a dream for a G.I. stopover on the way to the Coast. The town he invented was Las Vegas. His name was Moe Green. This was a great man. A man of guts, and vision, and there was not even a status or a plaque for him in that town. Somebody put a bullet in his eye. I knew Moe was talking loud and saying stupid things. When he turned up dead I let it do. I said to myself, This is the business we’ve chosen. I didn’t ask who gave the order, because it had nothing to do with business.” That exchange between you two is what makes people go to the movies. Didn’t you know Strasberg from when you first started acting? The perfection of being able to share that work with him after all those years—you must have felt very lucky. Not only was he a great actor but a teacher who taught more than acting—life.

PACINO: One night I went to the “Night of a Hundred Stars” with Lee Strasberg. There were all these people, from Orson Welles on. I remember Lee turning to me and saying, “You know, darling, I look around, and you know what I see? Survivors.”

SCHNABEL: He was talking about character, no?

PACINO: About people who have endured and come through, who still have that kind of spirit left. When you see that, there’s something encouraging about it.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE FEBRUARY 1991 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again click here.