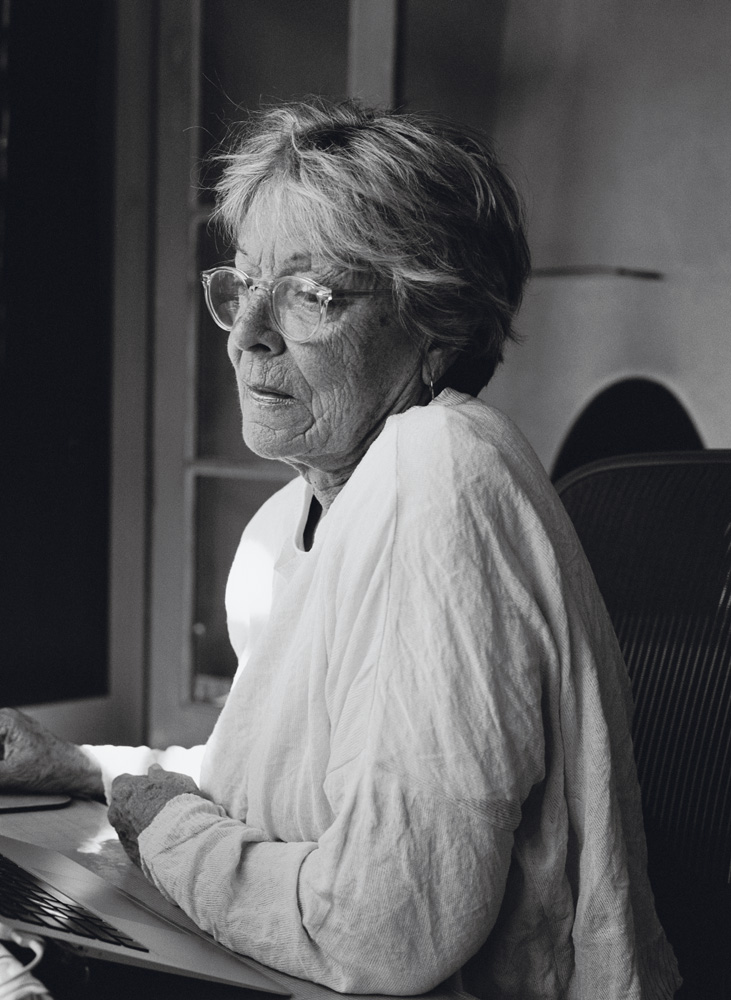

Joan Tewkesbury

Sometimes the most important word is no. It takes the pressure off. And also confessing to your crew that you don’t know what the fuck is happening right now is not bad either. joan tewkesbury

Very few directors and screenwriters start out as dancers. But Joan Tewkesbury has made a career bucking the expected paths and traditions. That unconventional approach started early, exemplified in the director she chose as a mentor and longtime collaborator: the great iconoclast Robert Altman. Jumping from a script supervisor on his iconic 1971 western McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Tewkesbury went on to write the screenplay for his quasi-gangster film Thieves Like Us (1974), and then to pen and develop what might be the most experimental Hollywood film of the 20th century, Altman’s 1975 ode to intersections, country music, and American politics, Nashville. It has become one of the most enduring and mythic cinematic masterpieces. After her time with Altman, the Redlands, California, native made her own name in the industry as a director, helming such diverse projects as her love-and-relationships film Old Boyfriends (1979) and her Southern period piece for television, Cold Sassy Tree (1989). No matter how experimental ’70s cinema became aesthetically and politically, Hollywood remained very much an old boy’s club, and Tewkesbury was one of the few women who broke through, claimed her own projects and voice, and continued to push the medium.

Now at age 79 and living outside of Santa Fe, Tewkesbury is currently working on a novel. She’s also an instructor at the Sundance Directors and Writers Lab, where, in the summer of 2013, I had the great honor of having her as my advisor. Tewkesbury, or “Tewkes” as she’s known at the Lab, has been working in an advising capacity at the Sundance Feature Film Program for more than a decade, and in recent years running her Designed Obstacles workshop, which teaches methods for grounding one’s writing in real life and honest emotional experiences. There seemed to be a kind of collective mythology around her, the Lab staff all whispering about her imminent arrival, as if royalty were coming. The other advisors talked about her workshop as if it were some cabalistic ritual, a place for epiphanies.

I’d never seen a picture of Joan Tewkesbury, but the day I spotted her on the Sundance campus, I knew it had to be her. In keeping with her dancing background, she glided more than walked across the room. And with a shock of Warhol white hair, she beamed from a hundred yards away. I was terrified and fascinated, a combination that usually leads to good things. Tewkes has been a mentor and friend since. When I was asked to interview her, I jumped at the chance and flew to New Mexico for the weekend. She lives in a serene, minimal compound (though she would surely say, “Fuck off, it’s just a house”) filled with carefully curated art, objects, antique rugs, and photos. One thing, for me, did stand out. Hanging on a dusk-colored wall was a photo shot during the production of Old Boyfriends. In the photo of one of the film’s stars, John Belushi, is at a breakfast table, reading the paper, holding a kitten by the scruff in his mouth. He’s looking up into the camera, his eyes soft, full of sweetness and life, and you get the feeling that on the other side of the lens there must be a close friend. He looks to be the consummate joker, a true artist—kind, vulnerable, wickedly smart, and slightly devious. I guess, for Joan, like attracts like.

MEREDITH DANLUCK: One of the most important moments at the Lab at Sundance was when I fully knew I had screwed up. I’d shot a scene where you are supposed to really identify and connect with the main character, and I only realized after we’d moved on, that we didn’t get it. I told the [assistant director], “We have to go back and reshoot that.” It was a lesson in understanding moments of compromise and moments you absolutely can’t compromise in making a film.

JOAN TEWKESBURY: Working with Altman, who was an artist, really showed me how imperative that was. He set up the dynamic of realizing that you can say, “I was wrong. Tear the set down. It’s got to be shot over there instead.” And that no one was going to die because of it. Yes, a couple of people on the crew might be pissed off at you, but tough shit. If you haven’t completed what’s important and what your story is about, then it’s stupid not to.

DANLUCK: When did you start working with Altman?

TEWKESBURY: 1970. I went with [actor] Mike Murphy to see a screening of M*A*S*H before it was released and we were introduced. At that point I was doing theater and directing plays on street corners and things like that. So I went to Altman’s office, and I asked if I could observe. He said no. He said, “You have to have a job.” He was getting ready to shoot McCabe & Mrs. Miller and he was going to Canada. He had finished shooting Brewster McCloud [1970], so I sat in the editing room over the summer with [Brewster McCloud editor and second unit director] Lou Lombardo, just watching the editing process. And then I went to Canada as a script girl because Altman ended up using the Canadian script girl, who was really a Scot, as one of the hookers. I took elaborate theater notes, instead of just, “Someone said you need to note this lens size.” But it was like film school for six months. And American Film Institute had just opened. So when McCabe was over with, I said, “Bob, do you think I should register for school?” He said, “What for? No! I don’t recommend it.” No one had told me that I had to type my notes and turn them in to Warner Bros.—they were all handwritten—so I stayed in Canada for another month and a half, just typing up about six months’ worth of footage. It was a review of what every single shot in McCabe had been. It was school. It was awful, but it was great. [Danluck laughs] Sometimes awful and great go hand-in-hand.

DANLUCK: Usually the best stories are the ones about something awful that turned out great.

TEWKESBURY: Yes. And then there are those stories that are awful and they’re just awful. There’s no getting around it.

DANLUCK: So when did you start writing for Altman? Wasn’t your first script Thieves Like Us?

TEWKESBURY: After McCabe, Bob said, “Nobody’s going to let you direct. You’re going to have to write something.” I was in the midst of separating from my husband at the time, so I wrote this really dark comedy, After Ever After, about the dissolution of a marriage. At first I didn’t think I could do it, so I hired a screenwriter and learned the lesson that no matter how many times you sit down with this other person and tell them the story the way you want it to be, they always write their own story. So I gave her a check and sat down and wrote the screenplay myself. I turned it in to Bob, who said he’d produce it. By that time [producer] Jerry Bick and he were in partnership to do Thieves Like Us. Bob said, “Have you ever adapted a book?” I said, “All the time, for theater.” And so I adapted Thieves, and I knew specifically it would star Shelley [Duvall], Keith [Carradine], Bert Remsen, Louise Fletcher, and John Schuck. The book was wonderful; you could just lift passages of dialogue right out of it.

DANLUCK: So Altman had the whole cast set before you started.

TEWKESBURY: Yeah, he knew exactly who the people would be. And at the time, Mississippi was offering the best tax breaks. So I went to Mississippi, and that was the first time I realized how much a place is a character. We shot all over the state. It was a very peculiar time. My hair was very long—it was the days of hippies—and I would go scout these small towns. I remember we were looking for a beauty parlor in this one town that was, like, three blocks long. I started on one side, and by the time I got to a beauty shop, everybody had sort of stepped out of their doorways to take a look at me. The woman in the beauty shop said, “Listen, girl, you either tie up your hair or somebody’s going to cut it off for you.” It was that time. The motorcycle man in Nashville was the Hells Angels guy who was helping us with cars on Thieves Like Us, and he was constantly being harassed. In Nashville, the character’s much lighter, played by Jeff [Goldblum], but in the original screenplay, it took on all those dark overtones. Anyway, there were interesting lessons on Thieves. I learned a lot about being in the world and accepting situations for what they are.

DANLUCK: Were you rewriting the script as you were shooting?

TEWKESBURY: Not so much on that movie, because it was really tailored for each of those actors.

DANLUCK: That movie seems fairly different from Altman’s other work. Maybe because it has this classic gangster quality to it, the shoot-’em-up—the stuff that you associate with big Hollywood movies. Was that a conscious decision?

TEWKESBURY: Bob’s feeling about it was that all those characters wanted to be famous, especially the character of T-Dub—all he cared about was getting his name in the paper. It was set in the era of Bonnie and Clyde, and they were capturing all the headlines. So these guys were doing their best to get a little action. It’s interesting because Nashville is also a movie about everybody trying to be famous in a way. So if the Hollywood gangster movie was front and center in most people’s minds, ours was the dopey version. They were sort of the gang that couldn’t shoot straight. They were not quite smart enough to pull it off. And the level of gunshots that were fired into that shack at the end of the movie was ridiculous. But, again, Bob wasn’t quite subtle, but there was always a point to these movies. If you look at Kansas City [1996], they’re in the same time warp, and those are particular memories for Bob that were pretty potent. So Thieves was his answer to the shoot-’em-up noir. And for me too, growing up, those were the B-movie classics that you went to see. Your mother didn’t want you to, but you did anyway. And also that life on the screen wasn’t quite as perfect as an MGM musical.

DANLUCK: Now, the big one: Nashville. Does everybody want to talk to you about it?

TEWKESBURY: Yeah. And the thing that’s interesting to me is that as the years have gone by, that film has become truer and truer. My feeling is that you, the viewer, are all of those people, that you share an aspect with every single one of those characters. So if there are 24 characters in the movie, the audience is the 25th character. And if you saw that movie at different times in your life, you would probably attach yourself to a different person every time you saw it. It was calibrated in a way that there would always be something fresh to an audience coming to see it, that they didn’t have to follow the same story line. And each actor playing those parts brought their whole lives to it too. It was like this huge math problem that may have started out as two plus two is four, but it ended up being 16. And that was perfectly fine. It made it more experiential than just a Saturday afternoon at the movies.

DANLUCK: It’s still one of the most radical movies ever made. It seems almost impossible to write and shoot.

TEWKESBURY: There were other films Bob did with a lot of characters. But in this case, with every single one of those characters, there was a full-on, flat-out biography, so each character could stuff them full. For me, one of Bob’s last films, Gosford Park [2001], had the gravitas of character in a way that Nashville did. The skill in the writing of Gosford Park was that it gave everybody enough ammunition that they could fire the gun with a direction, rather than a hope and a prayer, you know?

DANLUCK: How did you even start to write Nashville?

TEWKESBURY: I don’t know about the city today—I haven’t been there in 15 years—but back then it was like a small town built in a circle. If I saw you in the morning, I’d probably see you at least one more time during the day. So all you had to do was think, “If I saw you in the morning, what did you do until four in the afternoon? Who were you fucking that you weren’t supposed to be? Who were you trying to make a deal with?” You begin to make up these stories for all the characters. And in going to Nashville and looking at the people who live there, they were very kind, they weren’t naïve about their business, and they were extremely talented. But they might have been a bit naïve about the people who were coming into Nashville to record, people who were incredibly sophisticated and cosmopolitan and had different kinds of drugs—uppers and downers. So it was a moment of a lot of change. And again it’s about treating the place as a character. So the character of Nashville was a circle that was in flux. I didn’t know what the hell it was going to be about. I just kept going to places. Somebody said, “You should go look at that.” I had a yellow pad, and I would sneak into places and sort of smile, and hope for the best and take a lot of notes. I remember on the last night I was in town, the recording engineers at the place all the gospel music was recorded told me I needed to go to the Exit/In. The Exit/In was the after-hours place where younger musicians went. So there was all this different stuff going on at the same time. Barefoot Jerry was onstage at the Exit/In singing, “The words to this song don’t mean anything at all.” I still have their album. There was a girl who, I don’t know what she had taken, but she was severely compromised and having a difficult time at a table in front of me. And the Exit/In was on the radio, so everything was going out into the airwaves, and this African-American man came and sat next to me and started to tell me that he’d been in jail for 25 years and had studied law in jail and gotten himself out. He said, “What are you doing?” I said, “Well, I’m writing.” He said, “I should take you to the prison, so you can really get some stories.”

DANLUCK: Did you have any sort of organizing structure?

TEWKESBURY: What I do when I write or direct is to try to encompass it all. So I mathematically set up the trip, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday. And with the characters I had so far, which were about 18, I knew I had to see them every single day. That way I would never forget them. And they had to be vivid enough to make an impression, but they also had to overlap, either directly or peripherally. So you got this loopy-loop of civilization in a small place running around in a circle. And then Bob said, “This is okay,” but Nixon had just been reelected. We were all in Nixon-land in that moment; it was around the time of Watergate, and Bob had very strong opinions on politics. We had discussions about politicians and movie stars and singers and songwriters all wanting to be famous. So the political line was added, which brought another fork, and four or five more characters. So there were all kinds of truths but no truth whatsoever. What I loved about the character of the reporter Opal was that she’s there, trying to gather news. But she’s full of shit; she no more works for the BBC than you do. And she misses the main moment, which is when Barbara Jean gets shot. Which is often the case with people covering things. And basically Opal was inspired by Geraldine Chaplin. Bob and I had been at Cannes with Thieves Like Us, and she was there with her boyfriend Carlos Saura. Every time the two of them would go anywhere, somebody was in her face with microphones. So Bob said, “Be them.” It was perfect. Geraldine was pregnant.

DANLUCK: During filming?

TEWKESBURY: Yep, very pregnant. And all the speeches she made up, about the yellow buses and the junkyard being the elephant graveyard—hilarious. You can’t make that shit up. Geraldine was fucking brilliant. Certain people are cast who have strengths, so the idea for a director is to pull the strengths out and use them, not try to make them be something that you’ve set in concrete. And then there comes a time when you have to start taking things out. But, for the most part, Nashville was this giant collaboration. And that was sort of a daily thing, of just keeping track of the math so that somebody didn’t go over the top and become so much that you couldn’t pull it back. At one point, Bob had thought he would make two movies, only, there wasn’t enough story for two movies. There was a lot of footage, and, granted, some of it was very funny. First it ballooned into four hours, and gradually it came back to the original construct, because that was the playpen that could hold them.

DANLUCK: How did you set up improvisational scenarios for the actors to work with but not get lost in?

TEWKESBURY: Actors would come maybe two or three days before they were going to shoot, if they had been thinking about something improvisational. And then on the day of shooting, everyone would assemble on the set, wherever it was, and it would be not so much improvisation, but additions or suggestions. As the scene had been written, Lily [Tomlin] did not do the signing, but she created this character who had more balls than it had originally been written. Which was fabulous. The whole thing of signing to Keith, rather than feeling victimized by having been there or being guilty or any of that shit-no, man, she walks out as a fucking queen. Gwen Welles and the striptease and all of that went along absolutely as written. There was no deviation. Ned Beatty kept saying, “Oh, no, this would never happen.” But we had Thomas Hal Phillips on set, who had run his brother’s campaign in Mississippi, and was writing the political speeches for us, and he said, “Excuse me, yes it would.” The scenes were shot exactly as they were written. Ronee Blakley had come out with this thing of slowly unraveling when she tells the story about the chicken, quietly going crazy, which was terrific. So that stuff would be done on the day of. But previous to that, Bob and I would meet and sort of talk about it. Cristina Raines with the Noxzema cream all over her face—I mean, you can’t make that shit up in advance. That’s something that an actor brings to you. In working with Bob, what it really revealed was the generosity of everybody on a team; they created almost a force field. And it drives whatever the film is forward in a different way. And I think that all of us who worked with Bob, from Alan Rudolph [director who worked with Altman as an assistant director and writer] to myself, to Allan Nicholls [who worked with Altman as a writer, actor, and assistant director], every single one of us took that away, and tried as best we could, to re-create that kind of construct, for whatever we were shooting as directors. And it works.

DANLUCK: Can you describe that construct in a bit more depth?

TEWKESBURY: Inclusiveness. And for me, as a director, the casting of the crew is as essential as the cast of actors. I adapted a film for Faye Dunaway called Cold Sassy Tree, in which we sort of seduced Richard Widmark into playing opposite her; he told me that at this point in his life he had given up working with women and children. And to take this role meant working with Faye and Neil Patrick Harris, pre-Doogie Howser. But we managed to talk him into it. But just as important as that casting was my production designer, because we had to build a small town. And I cast Michael Watkins as the cinematographer, because he was attractive, fast, funny, and would keep Faye interested. And the costumer was a person Faye brought from England. So each of these souls made up this unit that could hold Faye quietly and supportively. And when you have to shoot, in a field, it requires everyone to be a team. We had minions tying red paper flowers into the grass, so there would be some sense of depth. We had to fill in the roads with dirt and rent a hundred turkeys. But stuff’s possible when you have a trusting team. And it’s fun.

DANLUCK: Especially when your crew is willing to go the distance.

TEWKESBURY: If this is too hard for them, you just say, “It’s been a pleasure meeting you, but this is not the job for you.” Bob was loath to fire anybody. But he was quick to find out who wasn’t interested in playing ball. Susan Anspach was supposed to play Ronee Blakley’s character in Nashville. And at the last moment she realized she wasn’t going to get paid enough, so Bob said, “Hey, I get it. But this is what we’ve got.” Sometimes the most important word is no. It takes the pressure off. And also confessing to your crew that you don’t know what the fuck is happening right now is not bad either. Because you can say, “I need five minutes here.” And you talk with whomever you need to talk to and fix it. Bob had Tommy Thompson as his first AD for the films I worked on. With Tommy, you realized what a brilliant first AD can be, and you learned that if you have a crappy one later in life, you have to get rid of them. It’s like a bad show runner for television. It’s not going to happen. Also laughing is very important.

DANLUCK: It seems like from Nashville on, you had so many opportunities in film and TV to write and direct. Did you ever feel like your gender stood in the way of other opportunities?

TEWKESBURY: Sometimes. As a dancer I had worked with really hard choreographers, Jerome Robbins being the toughest. And you learned what it is to hit against a brick wall. And you learned pretty quickly to go around the wall or say, “I can’t take this job.” I would usually try to go around the wall. It was the same thing in directing film. When I directed Old Boyfriends, it was only made possible because Paul Schrader had written all these scripts that he didn’t have time to direct. We had the same agent. But before I could even get to direct it, there were a lot of conversations about the fact that nobody thought I could pull this off. A lot of male producers, for whatever reason, called Paul and said, “It’s not going to happen.” I said, “Bullshit.” And Paul said, “We’ll proceed, but you have to know, there are a lot of people who don’t think you can do this.” So I did it. There’s the perversity—the sheer will that drives you to say, “Fuck you, friend, I’ll show you.” So there’s been a lot of that. A lot of this career has not been a straight shot, and one of the reasons I went into television is I couldn’t get any movies made. I didn’t want to sit around and wait for the next 400 years. There were only four or five women who were even trying to do films at that time. I wasn’t married to anyone who was supporting or financing this stuff, so television was my best bet. And I was able to work with some fabulous women, like Carol Burnett, Dolly Parton, Faye, Olympia Dukakis, Sara Gilbert. These were great dames. And in television you could write it, direct it, and get it on the airwaves. And it didn’t cost a fortune. Yes, you only had 18 or 20 or 23 days to shoot this stuff, but that was okay. Now people say, “Oh, God, I only had 27 days to shoot.” I want to say, “Right. As it should be.” You start and run until you drop dead at the end.

DANLUCK: When you really break it down, it’s shocking how few studio movies have been directed by women—even today. You almost expect these biases in other fields, but when you see it happening in a supposedly creative, progressive medium, it’s upsetting.

TEWKESBURY: I think in terms of the film industry, a lot of it came out of the military. All the time frames are set by military schedules. And it’s because a lot of the men involved in the business were in the Army. And that was the schedule: at the crack of dawn you get the light, you shoot the light till it turns dark. And it seemed silly because when I was a child and worked on a film at MGM, it was all on sound stages anyway. A lot of these men were bonded together by that experience of being in the military; they treated a film like an army march or something. Working with someone like Altman, however, he’d been a World War II pilot, but he broke down all of those militaristic ideas of “You move there, you go there.” So it was much looser and easier and funny. This is not to say that people did not have fun on movie sets before Bob Altman, but for me—I was in my mid- to late-thirties when I started working for him—it was a revelation. Because it wasn’t the choreographer hitting you over the head, saying, “Move your eyeball to the left.” It was someone saying, “Oh, wouldn’t mittens be funny.” I kept saying the kid looks like Hans Brinker on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. And Bob said, “Get him some mittens.” So it was that kind of brew that allowed for shit to happen that was interesting.

DANLUCK: Spontaneity.

TEWKESBURY: Absolutely. I remember that as a child working in films, there was no spontaneity. And the mothers of the children tried to keep them as young as possible for as long as possible, because they were the breadwinners in the family. There was a girl in The Unfinished Dance [1947] who was 14 and she looked about 8. She was not allowed to have milk, any of those things that would cause growth.

DANLUCK: That’s scary.

TEWKESBURY: Very scary. And there were rooms of these children. There were 36 kids in that movie, with Margaret O’Brien, Cyd Charisse, and Danny Thomas. At age 10, I looked at all that, and the only interesting job as far as I was concerned was the director, because he got to ride on the crane. [laughs] It’s interesting that the world sort of shifted with Bob. And then George Lucas and Francis [Ford Coppola], who were young then. And they infiltrated the world of directing, which upset a lot of older, male directors. And then suddenly Barbara Kopple wasn’t the only female director who could get her foot in the door. Joan Micklin Silver’s movies made money. That was the criteria. If your movie made money, then you might have a chance at a second go-around. It’s the same now. Okay, you’ve got your first movie made. Now what? It did not make $42 million at the box office. So what are you going to do? Your best bet, as you’re ending your first film, is to be writing the second one. So when someone says, “What do you have?” you’ve got something to give them. A lot of people don’t, because they get overwhelmed by that whole experience of promoting the movie and trying to sell it to 85 markets, and get it in to film festivals. And you kill yourself. So if there’s a way to start that process early, it would be terribly beneficial. Especially for women.

DANLUCK: [Filmmaker and Sundance alum] Pamela Romanowsky said something really great—she said that the gender of the filmmaker doesn’t define the gender of the movie. Which is just so brilliant and obvious.

TEWKESBURY: The thing that’s interesting about storytelling is people will say, “How do I write a movie I can get sold in this category?” For God’s sake, the first movie that you can get made will be your personal story, because nobody’s heard it before. Look at Rocky—nobody had told that story before. The best possible fuck-you is to believe enough in your personal story that you lay it down as harsh, heavy, and funny as you can. And make it for $1.95, if that’s what it takes. And that’s what it takes. [laughs]

DANLUCK: How difficult would it be to get Nashville made now?

TEWKESBURY: I don’t know what it would take. That movie was made for under $3 million. Everybody got the same amount of money. Nobody got paid squat. Except Bob. Bob always got paid.

DANLUCK: What is some parting advice for any first-time feature maker?

TEWKESBURY: To be completely open to whatever comes to you and resonates to your story. And maybe sometimes things come to you that you never, in a thousand years, would have included. But they strike a chord, so grab it. Trust your ability to know what’s true to it and what would carry you off into outer space. Also pay attention and really be aware of your community that you’re building around you. No, you’re not going to agree all the time, and you’ll argue over certain points, but do you support one another? And there’s no hierarchy in the director; you are in this mess together, and it’s much more fun that way. And keep laughing. The only thing that you have is your sense of humor. And get enough sleep. [laughs] And take your vitamins.

MEREDITH DANLUCK IS A PRODUCER AND DIRECTOR BEST KNOWN FOR THE BULL-RIDING DOCUMENTARY THE RIDE. SHE IS WORKING ON HER FIRST NARRATIVE FEATURE, TITLED STATE LIKE SLEEP.