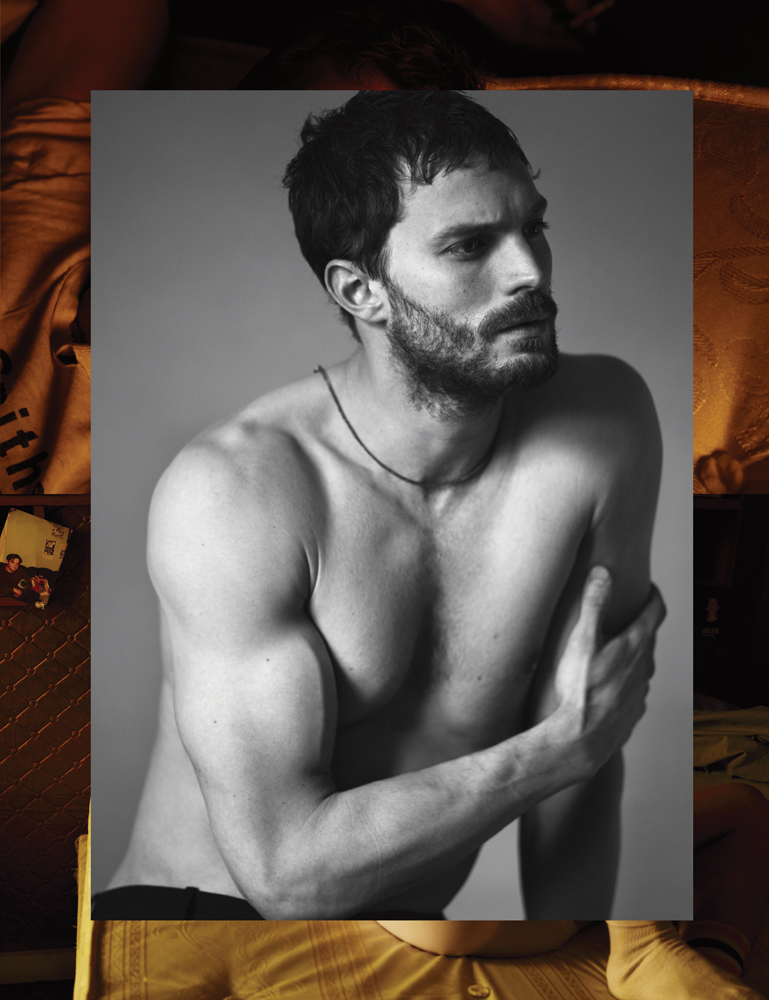

Jamie Dornan

I don’t like my physique. Who does? I was a skinny guy growing up, and I still feel like that same skinny kid. Jamie Dornan

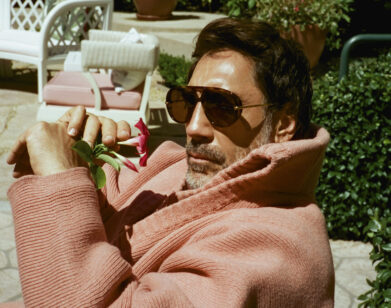

Before he became “a working actor,” as he now proudly calls himself, Jamie Dornan initially caught the public’s attention as a model—you may remember him from those greasy underwear ads with Eva Mendes, among many others. His first real acting gig, a small role in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006), similarly treated him as little more than a sex object. But what finally cemented his status as an overnight success—and the years of toil that generally goes with (and contradicts) that phenomenon—was his landing of the coveted lead in the forthcoming adaptation of Fifty Shades of Grey.

“I’d been auditioning for parts for years,” Dornan, 32, says on the phone from London. “I never got any better at it. I’m crap at auditions. I know there are people who can walk into those rooms and make those lines sing on the page and get the job immediately. I wasn’t one of them.” He pauses and laughs. “I’m still not one of them. Even after I got my first acting job, thanks to Sofia, I still went a while without working. If you ever wonder why some actors end up taking shit jobs, it’s because they have to pay the mortgage—or because they just want to work.”

All along, Dornan hoped he could convince producers that if only given the chance, he could do the work. That finally happened with his brazenly empathetic—and seductive—take on a serial killer, Paul Spector, in the British series The Fall. In it, he plays a bereavement counselor and apparently loving family man whose placid demeanor belies his appetite for inflicting extreme suffering. Dornan’s gripping performance is localized in his hands. “I wasn’t aware of it at first,” he says, “but the way I used my hands became a way for me to play Spector’s awareness. You see the difference in how he deals with his family, with his kids, and the way he approaches other things in his life.”

Stillness and wariness have informed many of his performances, from the alluring Count Fersen, in Coppola’s pop-inflected Versailles, to an unusual watchfulness in the 2009 slice-of-life short Nice to Meet You (“I can’t believe you saw that,” Dornan says, incredulously), to the breakthrough role in The Fall—and more than likely, as Christian Grey in next February’s adaptation of the soft-core novel Fifty Shades. He attributes his measured onscreen quality to preferring actors of the less-is-more approach, citing Al Pacino’s Michael in The Godfather and connecting that to the pantherish calm that Robert De Niro employed as Michael’s father in the sequel to the Mafia classic. “I don’t want to be showy,” Dornan says. “I’m not interested in seeing that, and I don’t want to do it.” He suggests that the quiet he performs rises from the types of men he’s taken on. “I’ve played a lot of broken people. Maybe the silences are about the different kinds of vulnerability in all of them.” When I mention that he’s often played characters with two sides, he agrees. “That’s true. Even Christian has two sides. Come to think of it, he has 50.” When I laugh, he barely suppresses a chuckle in response. “I guess I’m gonna be using that line all over the planet in a few months. Shouldn’t waste it.”

Mostly, Dornan comes off as a down-to-earth and forward-thinking guy, one who’s more than slightly abashed about his work. “I don’t like my physique. Who does? I was a skinny guy growing up, and I still feel like that same skinny kid.” When I noted that he will be unveiling the torso that has made him famous around the world for a movie-going audience, he again laughs over the absurdity of it all. “I’m still auditioning,” he avers. “I don’t really have choices in the material I get. So I have to make the choices in the way I play the characters. And I’m happy to get a chance to play Christian.”

Something else he didn’t have a choice about, but derives particular enjoyment from, is the range of actresses he’s been paired with on the big and small screens. Dornan’s power of observation, which has been key to his growing fame as an actor, comes to the fore when he discusses his admiration for such co-stars as Gillian Anderson, his detective nemesis on The Fall. “I can’t believe how simply good she is,” he says. He’s especially struck by the unique opportunity afforded him by the 2009 film Shadows in the Sun, where he performed with Jean Simmons—a star whose career spanned decades and saw her act alongside Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Victor Mature, and in two films with Marlon Brando—in her final role before her death. “She was, what, 79 when I worked with her? And when I think of all the films she was in, and how thoughtful and generous she was …” After an emotional pause, he resumes the conversation, “I have to be careful here, because I was almost gonna tear up. She started as a kid. She had so many great stories. She worked with Marlon Brando and Frank Sinatra—in the same movie! I’m sure she got sick of me asking her about that. She told me one of her first jobs was as Vivien Leigh’s stunt double. They rolled her up in a carpet and threw her into a pool for a scene where Vivien was to be drowned. She said she stayed underwater for what to her seemed like forever, but when she came up, she knew it was only a few seconds. She laughed about it, then she went from that to starring in Spartacus [1960]!”

Such experiences have given the Belfast-born Dornan perspective and a patience that he has made the bedrock of most of the acting he’s done. In between bouncing back and forth from London to Northern Ireland for the filming of the second season of The Fall, and tending to his infant daughter (“I don’t understand people complaining about babies. Sure, I miss a bit of sleep, but look at the rewards—better than not being able to sleep because of a hangover”), his displays of generosity extended even to me. A technical problem—when the first attempt at this interview was done over a long-distance call, with me in Krakow, him in London, and the recording being done via New York—made the recording unusable. And he graciously made himself available the same day this past May for a second take, no small thing with the demands of both our schedules. That’s how good of an actor he is—it never occurred to me that he wasn’t as involved for the makeup test.

I’m still auditioning. I don’t really have choices in the material I get. So I have to make the choices in the way I play the characters. And I’m happy to get a chance to play Christian. Jamie Dornan

ELVIS MITCHELL: Just when you thought you were done with me, there’s more.

JAMIE DORNAN: Oh God. What time will we speak tomorrow?

MITCHELL: [laughs] One of the things we didn’t talk about was that you are doing the horror web series Beyond the Rave [in which Dornan plays a soldier who spends his last night before shipping off to Iraq chasing down the love of his life, and getting pulled deeper and deeper into a circle of blood, evil, and electronic dance music].

DORNAN: Wow, we’re going to talk about that? [laughs]

MITCHELL: Yes, we are, because that’s one thing in which you get to run around and use some physical energy rather than remaining still. How’d you get involved with that one?

DORNAN: I met the producer at my sister’s wedding and was very fond of him. I liked what he was trying to do with the project, and after plenty of drink, I said I’d be involved. Then I was involved and it was a mad shoot. The whole shoot was a night shoot. I was sleeping all day, having no life, and then getting up, going to work at six in the evening and coming home at six in the morning—very strange. I don’t remember a great deal about that time. [laughs] But I made good friends. We were brought together through the lack of sleep.

MITCHELL: You’ve mentioned that you researched Ted Bundy in preparation for playing Paul Spector, the serial killer on The Fall—for playing that disconnect between his daytime life and his nighttime life.

DORNAN: Bundy’s a good example, in that no one around him knew that he was murdering lots of women. He kept that totally separate. It’s fascinating when you think of somebody you know—a friend of yours, a work colleague, or someone who lives next door to you—and on the surface, you have a regular, normal, placid relationship with them. You’re just totally unaware of what else is going on, which I thought was interesting for Spector. Bundy had two jobs in politics, was a law student, had steady girlfriends, and a good social group. When you watch interviews of him, it’s quite chilling how likable he is. He’s articulate and humorous, and definitely charming. But he killed dozens of young women. It would send you mad if you give it too much thought. It’s crazy that these people do exist amongst us; they don’t have to be some creepy guy with a scar across his face and a limp to be doing this kind of thing.

MITCHELL: Did it liberate you, to play Spector as charming, instead of as the archetypal serial killer—one of these guys who never speak and are really creepy?

DORNAN: A lot of that’s done for me, on the page, in [The Fall creator Allan Cubitt’s] mind. The occupation he’s given Spector, the family he’s given Spector, and the life he’s given Spector, I’m just trying to play that. What is creepy about that is the normality of it all. He’s a grief counselor, of all things. He has a wife and two kids that I think he loves. I think Allan would say that Spector’s incapable of love and therefore doesn’t love the kids. I would try to argue that slightly. I would say that he portrays a certain form of love, certainly to his daughter. In a way, I don’t think Spector’s that bad of a husband. He can be a bit despondent. And it’s crazy saying that, when you see what he’s getting up to, but I actually don’t think that negates the good qualities that he has as a husband and a father. I think he shows good qualities, despite the fact that he hunts and kills innocent women. It is all quite sordid. But I want to show how regular these guys can be.

MITCHELL: It makes me wonder if you have to find something about these guys that you—I’m not going to say “like”—but relate to.

DORNAN: I would go as far as to say “like.” I don’t think I’ll ever play a character that I don’t have some fondness for, or who doesn’t have some redeeming quality to me. I’m not sure I’ll play anyone more heinous than Paul Spector in my life, but I might, and I will only do that if I find something within him that is sort of acceptable. For Spector, despite all the horrendous acts, there’s something that I’m fond of in his character, and I think a lot of those characteristics in him that I admire, he uses for quite odious purposes. I wish I had his attention to detail, and his efficiency. [both laugh] I think you’ve got to learn something from every character you play. You’ve got to take something away, as an actor, as a person.

MITCHELL: Compared with some of the broken men you’ve played, Abe Goffe, in the continent-hopping miniseries New Worlds [a sequel to 2008’s two-fisted and equally hormonal, popular British action/political miniseries The Devil’s Whore, set during the English civil war], is almost a classic hero.

DORNAN: I think he’s broken, too. I see broken people as those who have been through hardship—whether it’s really ugly hardship like abandonment, abuse, something definitively life altering, like Christian Grey. Maybe in the second series of The Fall we will find out why Spector is the way he is—so I don’t want to say too much about that. But there are reasons for these people being the way they are, and that’s what drives them. I think for Abe, he felt an injustice was done to him. He was studying medicine when he was younger and couldn’t continue because his father was one of the guys who signed the death warrant of Charles I. So that spurred him on.

I don’t think [paul] Spector’s that bad of a husband . . . I think he shows good qualities, despite the fact that he hunts and kills innocent women. But I want to show how regular these guys can be. Jamie Dornan

MITCHELL: Your physical confidence really comes into play with Abe. But then you often seem to find a way to physicalize these guys you play so that it makes emotional sense to you.

DORNAN: Well, the thing about Abe was there’s a lot of talk, and he is one of those people who talks with his fists. As time goes on, over the four episodes, he has a massive change where he actually realizes that maybe words are the way forward. But you meet these guys, in any time period, who are very headstrong. I have mates like that who are just fucking aggressive. They move a certain way, especially around other people, around new people. They bristle up a little bit. And I tried to draw on some of that for Abe. He isn’t comfortable with company outside of his very select few.

MITCHELL: Do you respond to really physical actors?

DORNAN: It’s a hard thing to define, “a physical actor.” Every role is physical to a certain extent, but as a viewer, I don’t respond well to actors doing more than they need to tell a story. I get really thrown by that, and pissed off. Now and again an actor will blow my mind by doing something really unexpected, like Mickey Rourke or Christopher Walken—you have absolutely no idea what they’re going to do, which is really thrilling to watch. And then there are actors who think they have the same quality of Mickey Rourke or Christopher Walken, and just look really busy. They’re doing lots of things, but they could just stand there and say the lines, and it would tell the story in a far more pleasing way for me personally. I find myself approaching it in a slightly less-is-more way. And once you get into something, once you’ve got those first couple of weeks out of the way, really mad or gallant things start to happen. With the second season of The Fall there is going to be more to him than I planned for. It’s been over two years—I haven’t stayed in his mind for the entire two years, don’t worry—but when I’m in it, I do feel very comfortable in his skin, and that can only lead to rare things happening.

MITCHELL: What did you and Sam [Taylor-Johnson, the director of Fifty Shades] talk about in preparation for you playing Christian Grey—somebody who, to the world, looks like he has everything? What physical abilities did you bring to him to play him with vulnerability?

DORNAN: I think there was so much more to Christian that we covered—someone who is careful to keep himself in shape, someone who spends obscene amounts of money on presenting himself. A lot of that work was done in the gym and with costume. We didn’t talk about particulars of the way he would move. But I’m quite awkward in a suit because I don’t have an opportunity to wear a suit very often, and this is a guy who lives in a suit—the best suit. That has to have an effect. But when you end up in a suit for 80 percent of the filming process, you become pretty comfortable with it.

MITCHELL: It’s kind of hilarious—Christian would probably study photographs of a guy like you to see how he should look. [both laugh]

DORNAN: Right. I guess.

MITCHELL: I find myself fascinated by these contradictions. And obviously, one thing you’ve got to love about acting is just the ability to lose yourself.

DORNAN: I want to keep an element of myself in every character I play. And maybe that’s connected to finding something that you like in every character. Maybe they coincide. I get that the job is to make people believe that you’re this guy, and the more you can kind of lose yourself in it … I don’t know what I’m saying.

MITCHELL: You’re probably tired of talking to me, I’m sorry about that. [Dornan laughs] But one of the things you’ve been able to do is find ways to surprise audiences—with Spector on The Fall, for example. Because audiences know him a little bit better now, do you want to find more surprises, or do you want to play on what you’ve shown people already?

As a viewer, I don’t respond well to actors doing more than they need to tell a story. I get really thrown by that, and pissed off. They’re doing lots of things, but they could just say the lines, and it would tell the story in a far more pleasing way. Jamie Dornan

DORNAN: Well, we’re going to see more of Spector, but in a slightly different light. I can’t say too much more than that.

MITCHELL: But we’re old friends by now, you can tell me anything. [laughs]

DORNAN: Okay, so first shot, episode one, we find Spector … [laughs]

MITCHELL: Do you find it difficult to watch The Fall?

DORNAN: I don’t love watching myself, but I’ve seen it. I would love to watch it if I wasn’t involved. I love the story. So I sort of watch it for that reason, and because I think Gillian is so good. I don’t watch it going, “Wow, he’s good.” I sort of grin and bear my parts.

MITCHELL: How does it feel, going back and forth between film and TV?

DORNAN: I approach it all as the same thing. I’ve just finished watching True Detective, but I didn’t watch it thinking that Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson were acting for the small screen. I just thought they were fucking brilliant and giving epic performances. I think sometimes actors are drawn to good television because you have more time to sell it, you have more time to shape a character, and to tell a story, and that’s really appealing.

MITCHELL: Well, I know that you’ve got to jump on a Skype call now.

DORNAN: I can’t believe it. I’m so tired.

MITCHELL: Well, the good news is you won’t be talking to me.

DORNAN: It wouldn’t surprise me if you were on there, and your little face comes up in a wee box in the corner, just asking me the odd question in between me talking to this guy.

MITCHELL: If you see my face pop up—seek help! You need to sleep. Thanks again, Jamie.

DORNAN: Thanks, Elvis. Cheers, man.