IN CONVERSATION

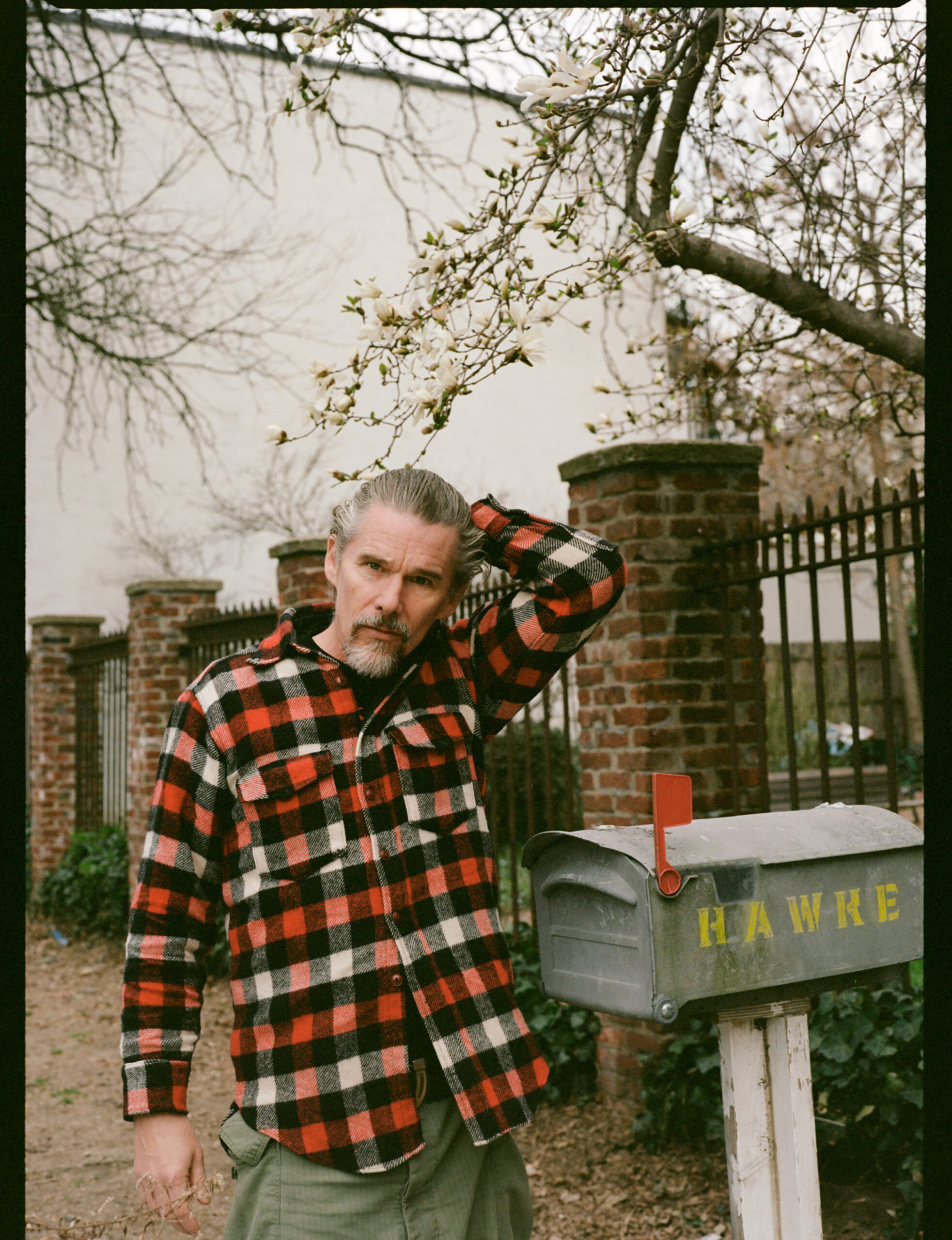

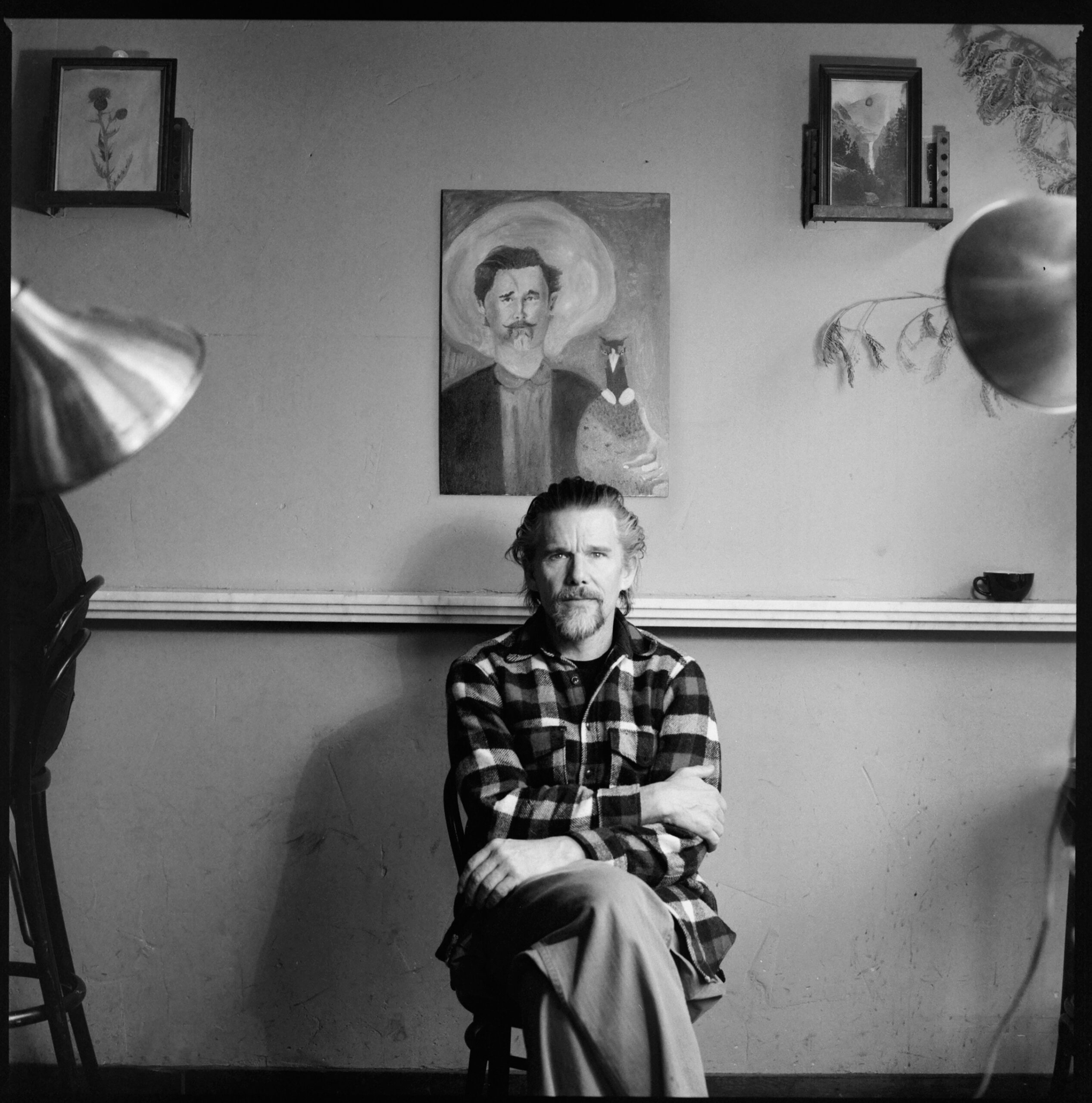

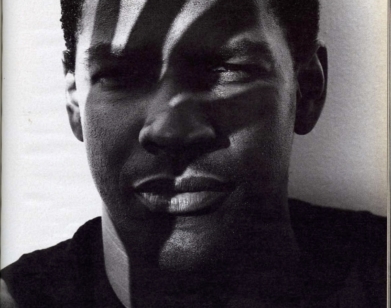

Ethan Hawke and Ken Burns on Faith, Fakes, and Flannery O’Connor

“One of the funny things about Flannery O’Connor’s life is that it was really undramatic,” Ethan Hawke says of the late writer, whose fiction, mostly set in the American deep south, made her an icon of 20th century American letters. But her stories, most famously those collected in A Good Man Is Hard to Find, belied a rather boring life, one she described as a rote cycle of writing and feeding the chickens. “I thought that was hypnotic,” Hawke, who’s now directed a movie, Wildcat, based on O’Connor’s fiction, told fellow filmmaker Ken Burns last month. Hawke’s fifth directorial outing, Wildcat is a winding, quasi-biopic that dips between O’Connor’s life and the fictional world of her stories. His daughter, Maya Hawke, who’s fascination with O’Connor preceded her father’s, plays the writer, shut in a small town in Georgia with her mother, played by Laura Linney. “I walked up to you and Laura and burst into tears,” Burns told Hawke on Zoom, remembering when he first saw the film at its Telluride premiere last year. Burns, for his part, is in the depths of creating another epic: a 12-hour docuseries called American Revolution, set for release in 2025. But in his admiration for Hawke and Wildcat, he found time to talk to the four-time Oscar nominee about faith, race, directing, Donald Trump, O’Connor’s complicated legacy, and the pair’s eternal love for Laura Linney.

———

ETHAN HAWKE: Lots of people I know are working on American Revolution. Different actors I meet are all like, “Yeah, you did that American Revolution thing, it was fun!”

KEN BURNS: I was just listening to you yesterday because an editor of one of the episodes had a question about a scene and we’d just thrown your voice in.

HAWKE: How’s it coming along?

BURNS: It’s good, we’re going to have screening for some of the academic advisors in 10 days, then we’ll go back. Then we’ll have another one in June and another one in August, and by that time we’ll be moving to a lock, I think. Knock on wood.

HAWKE: How long is it?

BURNS: It’s six episodes and 12-and-a-half hours. The last [episode] is at about two-and-a-half hours right now. If I can get it down to two hours and 10 minutes, I’ll feel like that’s worth making people sit for it, right?

HAWKE: It’s so challenging, because you want to give people the whole meal. But when does their brain get disinterested?

BURNS: You’ve got the privilege of their attention as long as you can keep it. So from the first note, first shot, all of a sudden you’re playing chess. If it’s a multi-part series, you also have this fourth dimensional thing that’s going on, too. You understand that they’ve had other information and you’ve permitted them to release it because you’ve faded to black and said, “see you tomorrow night” or “see you in a week.” But it’s really complicated, and the cutting room floor is filled with really good stuff.

HAWKE: I had a problem with one of the first things I ever directed. I had this scene with Michelle Williams that was one of the best things I’ve ever done and I had to cut it out of the movie because it made you want to see a different movie. It hurt, but it actually undermined the rest of the movie, it was like, “I should have made a whole movie about her character.”

BURNS: Aristotle tells us how these things are supposed to be arranged with a beginning and a middle and an end, and there’s supposed to be characters, protagonists and antagonists, and a climax, a denouement. But he doesn’t tell you what to do with all of that stuff. I was just looking at a film we made a few years ago on Muhammad Ali. We were working on it and there was this nice scene of him playing with his daughter and stealing her Cornflakes. I said, “Move that up to the beginning.” The beginning is just filled with all the iconic stuff and I thought, “He’s still just a dad who’s stealing his two-year-old’s cereal.” She turns around and knows he’s done that and hits him. So the first thing you see is a daughter hitting the greatest boxer of all time.

HAWKE: Amazing.

BURNS: Just that rearranging of molecules just I think added something to it.

HAWKE: The tip of the spear has to be so sharp and tell you what the thing’s going to be about and enter you into the world. It’s so important.

BURNS: What you did with Wildcat is so spectacular to me. You don’t have a simple narrative either. I’m so curious about that, because you are seamlessly moving into several of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories with the same tiny group of actors who are carrying the main narrative, the freight train. I saw it at Telluride and it was just one of the best films I’ve seen in the last year.

HAWKE: Well, thank you. I knew it would be a huge challenge. One of the funny things about Miss O’Connor’s life is that it’s really undramatic. At the end of her life, somebody said, “What would you say to a biographer?” She said, “Well, they have their work cut out for them because it’s going to be a boring story. All I did was write and feed the chickens.” I thought that was hypnotic, because I’ve always wanted to make a movie about the intersection between imagination and reality. Three things really interested me: reality, imagination. and this intersection with the idea of worship and faith. Is human creativity an act of worship? When you’re making these movies, you’re sharing with the world our collective history and you’re making it alive for us, and it’s real. Some of the times I’ve seen [Martin] Scorsese’s movies, they seem as real to me as scenes in my own life.

BURNS: Yes.

HAWKE: They change the way I think and absorb information, the way I look at the world. They penetrate inside me. So I found her work, but I couldn’t figure out how to make a movie about it. I was playing a part and I was away from my family. I was in Budapest and I just read all of her fiction. You start to see recurring characters, you start to see recurring themes, you start to see this human being dreaming these dreams. The pivotal moment of her life is when she was diagnosed with lupus, which for her was a death sentence. Her father had died of lupus. So she spent the next 15 years of her life not sure if she was going to see the following Christmas. I thought, “All right, that’s the event of the movie.” We’ll just build the imagination around that. But man, it was hard.

BURNS: The film begins with her coming back to Milledgeville, Georgia, and the progression of the disease has made it impossible to live the life of a writer, which in the United States means you’re in New York City with your publishers and whatever. She’s got a relationship to the inevitable fact that this is a species with 100% mortality, and that her’s has been accelerated. And out of this impossible situation she’s going to create art. But she’s also going to do it in America, in the South, where the dynamics of race are ever-present. I was just completely blown away by the way you organized the material and this extraordinary performance by your daughter [Maya Hawke]. You must be so proud.

HAWKE: Well, the most important aspect of the execution of the film was yes, Maya, and the next most important thing was that O’Connor really had one relationship, which was with her mother. It was a peculiar death sentence that Flannery O’Connor got, because the last place on earth she wanted to be was Milledgeville, Georgia. Her relationship with her mother was very challenged. Her father had died when she was young, they were alone in the world together, and Flannery wasn’t interested in organizing her life around romantic love. She wanted to be an intellectual and a thinker. She wanted to be Tolstoy. Her ambition was great. She was smart enough to know what great art was and to go after it, and to get stuck in Milledgeville, Georgia in this racist community was a peculiar burden. The revelation for me was coming across one small piece of biography that I found fascinating. In her writer’s room in her farmhouse, she had turned her desk against her armoire and wrote looking into this little piece of wood. She loved this quote that she put over her desk, “The kingdom of God is in the midst of you.” I thought, “Well, that’s really interesting. That’s what the movie’s about. It’s all right in our hearts. We’ll make the movie’s central journey about coming to that level of acceptance where you can be happy anywhere and not need anything.”

BURNS: This is the revelation of the movie for me. We wish to have an unbound relationship to the world, and yet the ways in which we’re constrained, either through loss, or in my case, the death of my mother very early on, are defining. She’s not looking out the window because of course god is not in some remote heaven, but present all the time.

HAWKE: All the time. There’s a quote that I found really inspiring in regards to this movie. I don’t know how true it is, but Saint Joan, when she was on trial, one of the jurors said to her, “Miss, I’m afraid you’ve been a victim of your imagination.” She replied, “How else would god talk to me?” I thought, “Well, that’s a really wonderful thing.” It’s always available to us whether we’re feeding chickens or taking care of our children or going for a walk or sweeping the floor or creating art. There’s a wonderful scene in the movie with Liam Neeson, and at the center point of it is that the aspiration for excellence is defined by yourself. You know what excellence means for you. That aspiration is, for lack of a better word, holy. I remember watching this movie back with the editor. It’s just a little game I play. “Am I comfortable with any level of criticism? Am I doing what I set out to do well?” It’s a little vulgar, but I call it the “fuck you power.” If you don’t like this movie, that’s fine. But this is what I’m trying to say and, given the constraints, I accept them.

BURNS: That’s an exhilarating feeling when you realize you’ve come to that “fuck off” moment. We’re in a place right now where religion is being used as a cudgel, and the way both you and Flannery O’Connor negotiate it is so spectacular. We’re in an age where I’ll believe Trump’s a Christian when he goes down to the border and washes the feet of the people he–

HAWKE: Yeah. I have to press pause here and say I had this thought the other day that if I told you a story about a guy running for office who was selling bibles on the side to pay his legal fees to pay off a porn star, you would say, “You stole that from Flannery O’Connor.”

BURNS: She understood the fakes, she understood the snake oil salesmen, she got all of that and still managed to maintain this vibrant faith. There’s a force to it. The opposite of faith is what we see all out there. It’s certainty. That kills everything. It kills possibility, it kills seeing the other, it kills the moment of reception. This is what Tolstoy knew. He spent his life arranging the wisdom of the world. I’ve been doing this for years, but every single morning I respond with a few-hundred other people to the same photograph in this Tolstoy calendar of wisdom. You realize the extent to which it’s not out there, it’s always in here. [Gestures toward himself] Whenever we make a “them” of someone else, we’ve limited our own possibilities.

HAWKE: I love what you said about certainty. The key word for Flannery was always “mystery.” When you start with the humility of that, then you can start to handle how two opposing truths can be true at the same time. Then, faith comes in.

BURNS: The writers and the artists who are out ahead of that become a polestar for us. How do we understand that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts? That’s the mystery you’re talking about.

HAWKE: That’s the space between where god lives. I knew that for Maya to succeed and for the movie to succeed, we needed an artist on set, and that’s Laura Linney. My biggest achievement as a director was getting Laura to be in the movie, because she ended up showing Maya what excellence at this profession looks like firsthand. I’m not even talking about the details of the performance itself, I’m talking about the way she attacks material, the way she handles the hair and makeup trailer, the way she works with the assistant directors, the way she works with her own instrument. I’ve had this experience as a young actor. What happened to me is dangerous, and I don’t really advise it. I learned on the job, and I was very vulnerable to whomever I was working with. I was really lucky. I had these amazing mentors, Peter Weir and Richard Linklater and Olympia Dukakis, people who were feverish thinkers. They weren’t trivial people chasing awards. They were really interested in contributing and being part of the artistic journey. I’ve known Laura since I was 21, so we’ve been watching each other grow up, and I thought, “Wow, the greatest gift I can give whoever is going to play Flannery O’Connor is this person.”

BURNS: How great to have a secret weapon like Laura to ground the entire risks of this.

HAWKE: I’m asking each of these women to play five or six characters, and I need it to be one performance. That’s a riddle, and she knew exactly how to do it. She and Maya started talking. They would go into the hair and makeup trailer and talk and find their voices. I’m just indebted to Laura for her aspirational excellence and how contagious it is.

BURNS: She’s a wonder. I’ve known her for decades, too. There’s still the essential character, but you can go from being a frumpy buttoned-down writer, condemned to go back home, and suddenly become a voluptuous woman seduced by another, by going through a portal. So I would like to say, “Yes, Laura. Yes, Maya.” But also, “Yes, Ethan,” for the directorial chops that permit these portals to open up.

HAWKE: I directed my first play when I was in my early 20s. I’d been acting since I was a kid and I started getting interested in directing, but I always came at it from the vantage point of acting. Peter Weir, when I was young, created this environment in the movie Dead Poets Society, where we were all filmmakers together. He was inviting people, and he was so confident that he could really empower others. There’s a certain kind of confidence that has to have power over people.

BURNS: A Hitchcock that says, “They’re cattle.”

HAWKE: They’re cattle. But Peter was the opposite of that. He was like, “I know what this painting is going to be. I’m in charge, so does anybody have ideas to make this better?” It was an incredible experience, and I thought that’s what making a movie was like. Then I entered the professional world after that movie.

BURNS: “Hit your marks, buddy.”

HAWKE: This fear that something might go wrong and we might fail. It’s so hard to have confidence when there’s all this fear in the room. So I started directing, wanting to create a space for actors that was like the space I wanted. I only wanted to direct so that the acting could be better. Then during the pandemic, I followed in your shoes, and I made this really long-form documentary, where I learned about the art of editing.

BURNS: It’s something else.

HAWKE: It’s an amazing art form. You hear people say, “That’s a good shot.” But the shot is neither good nor bad, it’s how it’s in relation to the rest of the piece. This is the first movie I’ve made where I feel like my toolkit expanded, because I was understanding how the relationship to the camera and the editor and the actor are this dance. It was a very different experience coming to set having spent two years in the editing room.

BURNS: It’s really true. And the art of editing in a feature film is really different because the director gives you enough coverage that the art comes in your choices. In a documentary, you’re not talking about coverage. If you’re doing a subject like the Civil War, you’ve got lots of photographs, lots of newsreels. But I’m doing it on the Revolution, so there’s not a single photograph, Ethan. It’s a Thelma & Louise moment where you’re off the cliff. The only thing that’s going to help is the editing, and that is accepting that you’re not choosing aspects of coverage, you are really inventing the story as you go along.

HAWKE: It’s much more like writing a novel, because you’re writing the movie with your editing. You’re creating the movie’s psychic life with how you juxtapose this image with that one, how it’s relating to the voice, how it’s relating to the music. It was extremely fun with Wildcat to feel like my toolkit just got a lot bigger.

BURNS: Maybe to just bring this to a close, I’d say Wildcat doesn’t have the noise and the din of the things that have compelled our attention in the movie arena, but it has a perfection to it and a quietness that makes distinct its experience, that sets it apart from all of these other places with great art in places in it. This film required an enormous amount of risk. I just salute you for the accomplishment.

HAWKE: It’s an honor for me to have you spend an hour of your life talking with me. I feel so grateful to you for your work. I so appreciate your love and support.

BURNS: Anytime, anytime. Maya is phenomenal, and Laura and Liam, it’s a wonderful thing. Flannery O’Connor and her stories are just singularly important, so thank you for that great gift.