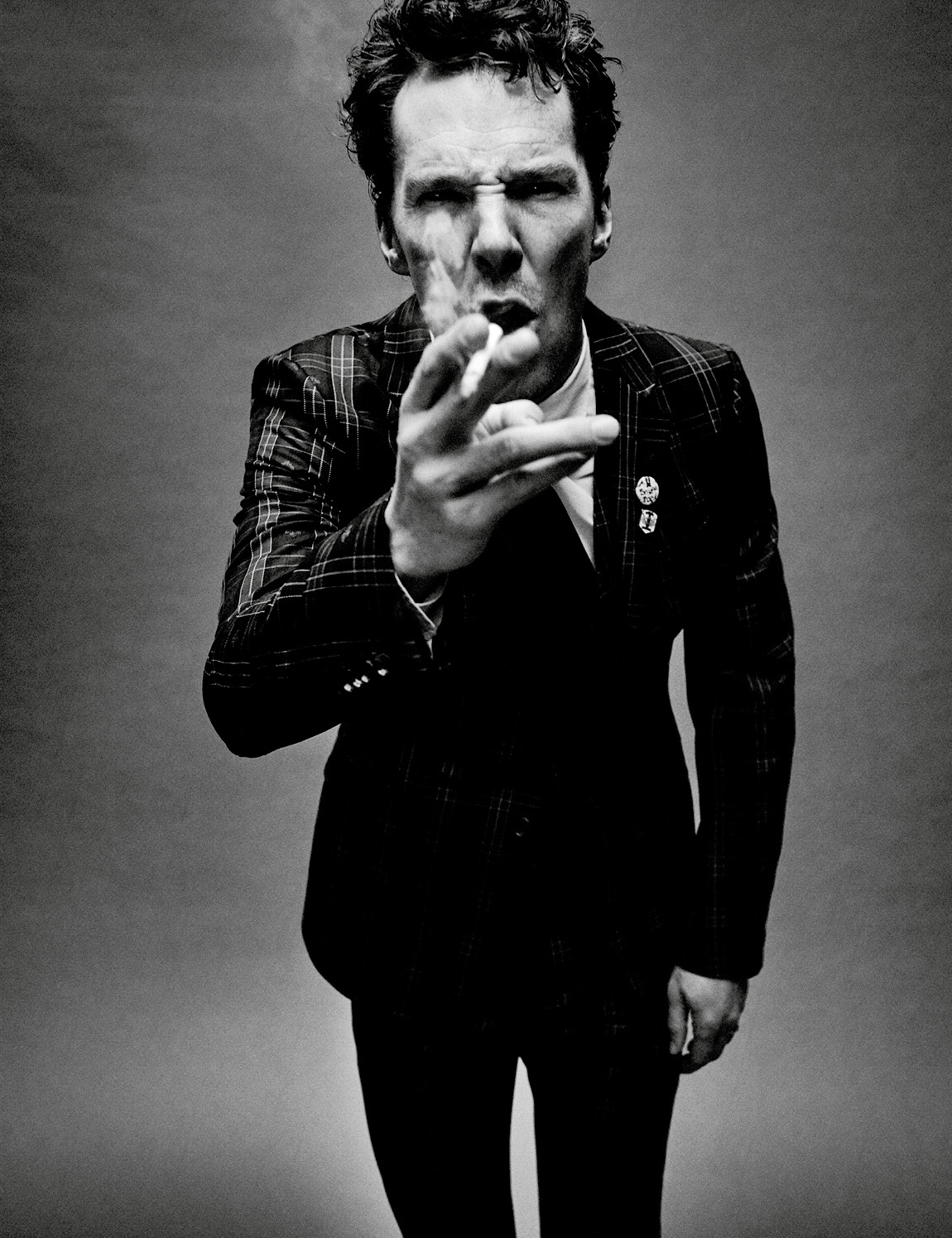

Benedict Cumberbatch

It seems like a lot more than seven years have gone by since Benedict Cumberbatch first donned his deerstalker as Sherlock Holmes, the alarmingly incisive yet socially inept detective in the BBC series that catapulted his Hollywood career. That’s because, in the ensuing time, the London-born actor has graduated from fan-girl obsession to franchise superstar, while steadily appearing in a succession of prestige projects in theater, film, and television. His mix of gravitas and humility works exceptionally well in fantastical worlds: as Khan in Star Trek Into Darkness (2013); as Smaug the dragon and the Necromancer in The Hobbit film series (2012, 2013, 2014); and as Dr. Stephen Strange in Marvel’s Doctor Strange (2016), a role to which he will return in next year’s Avengers: Infinity War. Back on planet Earth, Cumberbatch has a knack for inhabiting the minds of geniuses, empathetically depicting WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in The Fifth Estate in 2013; Alan Turing in The Imitation Game the following year (for which he earned Golden Globe and Academy Award nominations); and, most recently, Thomas Edison in The Current War, in theaters next year.

Now 41, Cumberbatch is considered one of the most accomplished and ambitious actors of his generation. It would be an understatement to suggest that he has a serious streak, but as his friend, the legendary Radiohead rocker Thom Yorke, is determined to prove, all men—no matter how focused—contain multitudes.

THOM YORKE: I don’t have any chronology to my questions. My approach is a bit more random, a bit more Just Seventeen [an out-of-print British teen magazine]. I actually want to start with the year you taught in a monastery in Darjeeling when you were 19. How was that experience?

BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH: It was in an exiled Tibetan community, just outside of Darjeeling, on the border. It was a little hill station town. I was one of five teachers who had done a training course. It was extraordinary, but it was quite an isolated experience.

YORKE: How long did you do that?

CUMBERBATCH: It was five months. I spent half a year working odd jobs to build up funds for the airfare and to pay for the course. You’re not paid for the teaching; you’re paid in experience. You’re surrounded by the monks and their lives. It was a small monastery, and the top floor was the temple. I was living on the bottom floor, which was pretty damp and had huge spiders. I think it was just near the end of the rainy season; I can’t remember, but it was cold. And because it was so high up, you would open your window, and the clouds were like dry ice rolling across your desk. Nature was ever present; that was gobsmackingly beautiful, as was the spirit and nature and philosophy and way of life of these monks.

YORKE: It sounds like you absorbed a lot of that, just by being there. You didn’t have to study it.

CUMBERBATCH: Exactly, it just seeped in. The personalities of the monks were louder than any lesson.

YORKE: That’s the ultimate teaching, isn’t it?

CUMBERBATCH: It is. By the end, I was so curious to know what the hell they were chanting, why they were doing what they were doing, and how to do it myself. I was like, “How do I go further into this world?” After the course, I did a two-week retreat with one of the other teachers.

YORKE: You were 19 and signing yourself up to sit on a cushion for how many hours a day?

CUMBERBATCH: Many. And only sleeping about four, and eating, like, porridge and maybe a little stew. That part of the retreat was intense. We were with the monks—my god, what discipline they had. It was revelatory. There are these stories and parables and tools with which to channel your focus and meditation and practice, and begin the path to enlightenment. It was a bit cult-y; there were a few nervous, out-of-the-corner-of-the-eye looks between us Westerners. The person who was overseeing us saw that we were really committed, and he also saw that it was just too much. Our busy minds had to be really suppressed. But it was the chance to begin something. I’m so grateful that I had that experience.

YORKE: It surprises me that 19-year-old kids signed up for this stuff. If I had done that at that age, I probably would have run away and found something to drink or smoke. In a way, I’m jealous that you had that experience at that age, because presumably it set you up in a different way for life.

CUMBERBATCH: It was massive. I really cannot get over the generosity of our teacher. He said, “Don’t punish yourself. You’re going to be a student at a university in the north of England. You need to have your experiences and have your fun, and not judge yourself. Don’t live in guilt and regret.”

YORKE: What I would have given for someone to tell me that at the age of 19. [laughs]

CUMBERBATCH: What was your experience at that age? Were you searching for something?

YORKE: I took a year off after school, basically doing shitty jobs, earning enough money to record demos, and sending demos off. And then I got bored of that and went to art college, and had a completely different trajectory. Art college blew my mind, because I experienced being with creative people for the first time and feeling like I belonged. But the ambition and the obsessiveness that I had became debilitating later on, and I really could have done with someone, at that time, sitting me down and taking care of the other side of me.

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah, but then I went in the other direction completely, and not as any kind of clear rebellion. I became kind of a party animal. I had a massive crash. My health suffered. I was just overdoing it. That person could not be further from the one who emerged from that earlier experience. I regressed massively.

YORKE: I was curious to know if you’ve ever taken a long period and removed yourself from the trajectory that you’re on. Do you ever feel the need to step off the train? The reason I ask is because, as I was following my trajectory, I never saw out of it. I never thought about it until one day I was no longer in my body. I had a full crash and had to stop—for a very long time. And then I started studying meditation. And when I did finally sit down, I found myself on a retreat, sitting on a cushion, and it was like someone had stuck a radio to my head and turned it up full blast. I was like, “Oh my god!”

CUMBERBATCH: It’s so loud when you stop to listen to it. Because you’re just in the flow of it all the time, picking out whatever the loudest thing is, or the most negative.

YORKE: I would sit down in my studio, and as soon as I started working, the voices would start telling me, “You can’t do this, you can’t do that,” so I had to stop. I had to figure it out.

CUMBERBATCH: I’ve definitely had breaks in that sense. And I’m amazed at the trajectory you’ve been on. The incessant demands of record labels, all of that. In many ways, I think I’m on a slower trajectory. That’s something I have to work on: to separate what really matters, to conserve energy by not worrying about what other people think. I mean, nothing really prepares you for all the stuff—

YORKE: But you did have parents who were in the same business.

CUMBERBATCH: That has helped massively. Even though their experiences were different from mine. I wasn’t a child actor brat; I didn’t travel with them in the circuit. But I got a look into their world, so I did know what I was getting into, to an extent. And they are a constant source of grounding. My massive motivation in life is to make them proud. But even that has to stop at a point.

YORKE: So this film that’s about to come out, The Current War, about the battle between Westinghouse and Tesla, is something that my bandmate Ed [O’Brien] became obsessed with a few years ago when he read a book about it.

CUMBERBATCH: It’s about these amazing men, this massive miscommunication, and egos. It resulted in the missed opportunity of collaboration unlike any other.

YORKE: We’d be living on a different planet if Tesla had won this.

CUMBERBATCH: But he was such an outsider in New York. People didn’t understand his Serbian accent. It didn’t help that he was speaking like a prophet. He was talking about things he’d formulated in his mind, but didn’t have models for: the wireless delivery of energy, let alone communication. Like all visionaries, he dared to formulate beyond the constraints of the status quo. The awful lesson of history is that we too often ignore these people, just because they’re foreigners or different from us.

YORKE: But he did build some of this stuff, yeah?

CUMBERBATCH: His work is still massively influential on the way we live our lives. And I’m going to forget every single thing that he actually did. [both laugh] He’s without a doubt the most extraordinary character, and Westinghouse is the most humane, and Edison the most flawed. You have these three men all going for an understanding or control of the electric current: Edison being very proprietary; Westinghouse trying to build the bond of friendships and bring his system to a mass market; Tesla working for Edison; Edison not taking Tesla’s advice and going to Westinghouse and forming a relationship. Tesla gave Westinghouse his patents. It’s amazing. What could have been is the real tragedy.

YORKE: Okay, stupid questions now. Just Seventeen time. Are you good at saying no?

CUMBERBATCH: No.

YORKE: [laughs] Are you a good driver?

CUMBERBATCH: I think I’m a very good driver. Apparently, the cause of road rage—as with most anger—is some kind of superiority complex, which, god knows, cars foster.

YORKE: The best time to listen to music is in the car.

CUMBERBATCH: Oh, yeah. I first listened to your album A Moon Shaped Pool while driving across your home county.

YORKE: A plug!

CUMBERBATCH: A plug. It was fabulous. It was a great way to hear it for the first time.

YORKE: It was definitely written for cars. Okay, another one: Do you trust easily?

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah.

YORKE: You have to, right?

CUMBERBATCH: You do, and sometimes you don’t. Sometimes during a conversation with a journalist— where you are answering things you never normally talk about, not even with some of your closest friends—you end up being quite confessional, and you don’t think about the amplification of that. No matter how fancy these journalists are, they have editors or political leanings behind their publications, which means that, basically, they’re going to shape what you’ve said into an article they’ve already written. So you have to be really careful with your words. I still find that difficult, as any person who deals with the press will tell you. That’s why it’s nice, with this one, to talk to a friend. But sometimes with a coffee and a friendly smile, I suddenly start talking without thinking about how it’s going to be read.

YORKE: Well, I’ll stop you if I think you’re digging a hole, all right?

CUMBERBATCH: Please do, thank you.

YORKE: Are you spontaneously goofy?

CUMBERBATCH: Spontaneously goofy is a qualification I’m not sure I can own up to.

YORKE: Do you run from trouble, or do you stick your face in it?

CUMBERBATCH: I think I’ve had very knee-jerk emotional reactions to things, and sometimes I’ve said things without thinking. Being overly emotional clouded my judgment.

YORKE: You’re talking in terms of what you say to people?

CUMBERBATCH: Situations where what I say echoes much further than what is healthy. I would love to just have the work do the talking. We’re in positions where people ask us questions; they want to know about more than just the work. And it can go into areas where I’ve completely shot my mouth off, whether it’s too much about my private life or being too opinionated about things in the world. I think the better thing to do—I’ve learned this from people far wiser than me—is to do very good, quiet work behind closed doors.

YORKE: Every time you take any type of moral stance, you will get fire.

CUMBERBATCH: There are other people who don’t mind shouting from the pulpit and being judged for it, and they do a hell of a lot of good—real, on-the-ground, life-changing good. So I think it can sometimes be a balancing act.

YORKE: I think that whatever you choose to do, you can’t find yourself in a position where you’re damaging your ability to do the rest of what you do. I’ve found myself in those positions far too many times.

CUMBERBATCH: I don’t call myself an expert because I’ve played experts. I know a little bit about very little. But it’s very hard to not be drawn into saying something, especially if it has to do with the work.

YORKE: Speaking of your work, have you ever taken on a role and then gotten to a point where you felt like, “I’m out of my depth here,” and wanted to pull out?

CUMBERBATCH: Lots of times. But if you can’t fail, you can never get better. And these weren’t total failures, these enterprises, but there was a lot that wasn’t right about them. One of the first roles I had on stage was with a brilliant director in a brilliant play with a brilliant cast, but I just couldn’t find my way into the heart of the character. I found myself straining a lot.

YORKE: Just in rehearsals or when it started?

CUMBERBATCH: When it started. I felt lost. That was [the Eugène Ionesco play] Rhinoceros. I don’t mind saying the name, because I’ve talked about it. It was partly because of where my head was at, and it was a big leap of discipline. I don’t think I was prepared for that. I don’t think I had the full tool kit to do it justice. It’s a very difficult play, it’s an extraordinarily difficult part, and I never felt I really got it right. Far from it. To a degree, Hamlet was the same. But not to do with the production or anything else—the challenge of doing that night after night was just the most extraordinary.

YORKE: That’s when we met! I remember coming into your dressing room, and your voice was shot because you’d been doing four weeks of performances and matinees, right?

CUMBERBATCH: Eight-show weeks.

YORKE: You were doing this full-on emotional thing, laying it all out on the floor, doing it again and again, getting up in the morning, running around, and then doing it again. I would have gone stark-raving mad.

CUMBERBATCH: [laughs] No, you wouldn’t—the training gave me the building blocks to get through it. A production of that scale, in a theater that big, you are going to struggle to keep your voice at first-run perfectness. All that work I did—the pull-ups and pushups—helped keep my body fit. Hamlet, the show, is a cardiovascular workout of about three hours, never mind the mental, soul-crushing element of it.

YORKE: I was well impressed. I saw in you a man who has dedicated himself to his work, while I complain about having deadlines. I’ve got a couple more Just Seventeen–style questions. Do you have slippers?

CUMBERBATCH: Yes, too many.

YORKE: Do you have reading glasses?

CUMBERBATCH: No, but I am shortsighted. I need them for watching movies or concerts. It’s not a hipster affectation; I do have poor eyesight. This is how ridiculous my life is: I’ve had the test for contact lenses, but I haven’t found a half-day where I can go to the optician.

YORKE: Do you walk around the house muttering your lines?

CUMBERBATCH: Hell, yeah.

YORKE: My girlfriend does that.

CUMBERBATCH: It’s really the only way, unless you have someone with you at all times who can run them with you.

YORKE: I’ll be walking around the house and I’ll hear this chatter. And I’m like, “What the fuck is that? Oh, she’s practicing her lines.” [laughs] It’s like someone speaking in tongues.

CUMBERBATCH: Does she do other people’s cues for her lines as well? My dad used to do that. That’s weird, to hear your dad talking to your dad.

YORKE: Yes. Do you practice laughing or crying? I have this image of Benedict in the bathroom going, “Ha, ha, ha, ha.”

CUMBERBATCH: I probably have cried on the toilet. I try not to, though, because I have people in my house who would be disturbed by their dad having such a strange, isolated mood swing. I think it’s important to be able to do some of that in some kind of enclosed space. It’s about finding triggers and trying very hard to find that within your characters and their backstories, and not within your life, because that can get out of control. Laughing and crying are really similar—what happens to your body. It’s a very similar process in your diaphragm. Like a musician, you have to do your scales once in a while and warm up your voice.

YORKE: Do you have a good relationship with your ego? You know, that bit of you that gives you what you need in order to do the things you have to do, but at the same time can start to control things if you’re not careful.

CUMBERBATCH: That’s a very good way of putting it. And, yes, I think I’ve found that balance. But I have pitfalls. I have emotional responses to things that are really not about me. They’re about other people.

YORKE: When you’re in work mode?

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah. That’s something I have to work on: to separate what really matters, to conserve energy by not worrying about what other people think.

YORKE: Do you bring your work home with you?

CUMBERBATCH: When I walk through that door, it’s about home. If I didn’t do that, I’d become consumed by one thing only and damage the people who love me. And it would damage the work.

YORKE: Are you going to do theater again?

CUMBERBATCH: There are plans afoot in the not-too-distant future, but not this year.

YORKE: Do you write? I’ve got a feeling you write, but don’t show it to anyone.

CUMBERBATCH: You’re absolutely right. But I don’t think I could form my writing into scripts or novels. It’s so sporadic.

YORKE: How do you feel about the words you’ve written?

CUMBERBATCH: My writing’s pretty poor. I often think, “Who’s this for?” Sometimes it’s impressions of the day or my life, or it’s fiction. Sometimes it’s about things I want to remember, or I try to write in really awful French.

YORKE: Are you good at French?

CUMBERBATCH: No, not at all. But it’s one of my ambitions. I’d like to be able to dream one day in French. Italian and French are the two languages that I’d like to know.

CUMBERBATCH: What’s “kisses” in Italian? I can’t remember.

YORKE: Baci, baci.

CUMBERBATCH: Baci, baci.

YORKE: Baci, Cumberbatch-y.

CUMBERBATCH: This is very Just Seventeen. Please don’t use that.

YORKE: Can you imagine ending on that?

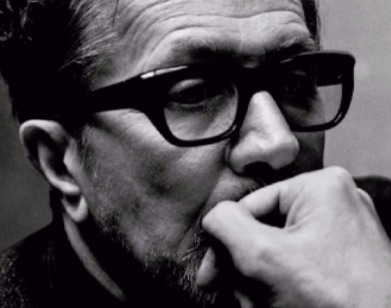

THOM YORKE IS THE FRONTMAN FOR THE LEGENDARY ROCK BAND RADIOHEAD. HE RECENTLY COMPOSED THE SCORE FOR THE REMAKE OF THE HORROR FILM SUSPIRIA, DUE OUT NEXT YEAR.