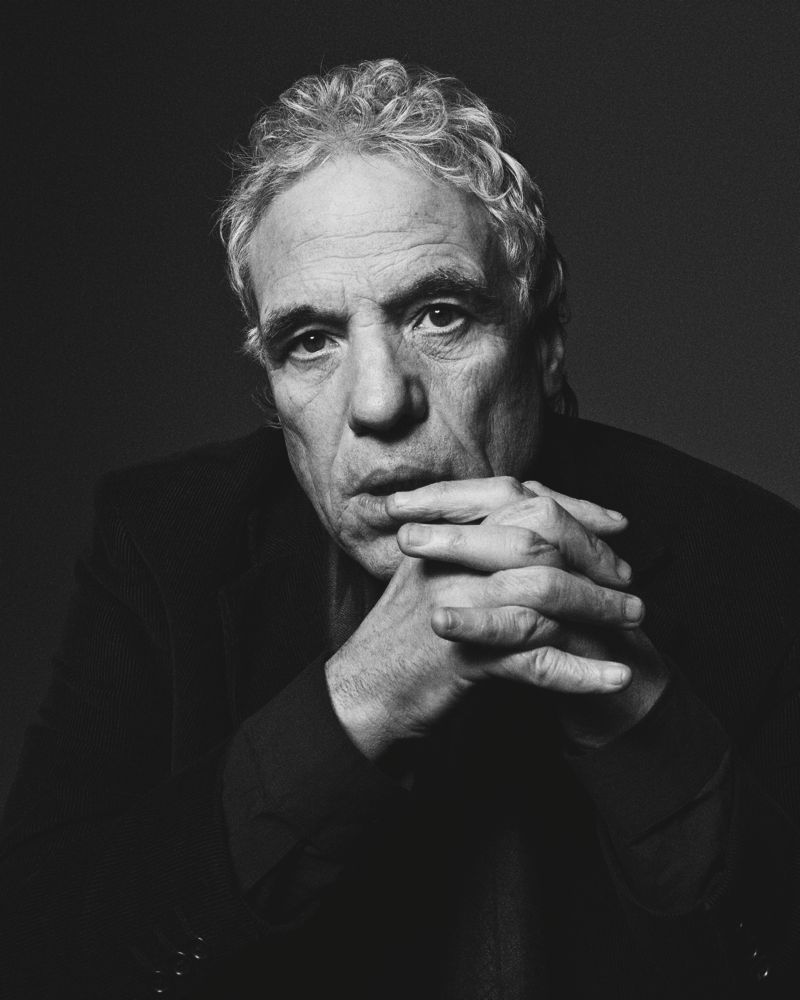

Abel Ferrara

When you get to the finish line, man, if you’ve got five people there, you should kiss their feet. Abel Ferrara

Abel Ferrara has been making films since he was 16 years old. For more than four decades, his hometown of New York has proven a dependable canvas, and much of his early exploitation films were born out of the post-hippie, post-punk, stretched-to-the-limit city of the mid- to late 1970s. Films like The Driller Killer (1979) and Ms. 45 (1981) paint a bloody, vengeful, bleak cityscape, and many of those early movies have gone on to become cult classics. Ferrara became more widely known for features such as King of New York (1990), Bad Lieutenant (1992), The Addiction (1995), and The Funeral (1996), with their antiheroic protagonists skirting social norms and crossing various legal and behavioral lines. In all of them, there is very little in the way of redemption. The same pool of actors appear again and again in Ferrara’s work—among them Harvey Keitel, Willem Dafoe, and Christopher Walken—and the narratives are often laced with bad cops, drug dealers, and urban isolationists caught up in corruption and crime.

At 61, Ferrara hasn’t softened, although he may have changed his perspective. His most recent film, last year’s 4:44 Last Day on Earth, focuses on a couple facing the apocalypse, and while not free of his usual dose of violence, the movie does exude a certain humanity and compassion.

Ferrara is currently working on a film about Dominique Strauss-Kahn, but it is another film he’s working on that connected us in a collaboration that took nearly two years to complete. I initially reached out to him two years ago to talk about the controversial Italian director and social critic Pier Paolo Pasolini’s death (Pasolini was found brutally murdered just outside Rome in 1975) for an art video I had in mind that would show Ferrara speaking about his take on the director. There’s a lot of conspiracy surrounding the subject of Pasolini’s death—different stories of who did it and/or who didn’t and why. But I was interested in the moment where the truth doesn’t matter so much, where the event itself supersedes fact and becomes cinematic. As it turned out, by mere coincidence, Ferrara had been working on a script about the director’s life. Pasolini, it seems, was in the air for both of us. And so began our collaboration.

We met in May 2011 on a street corner in Little Italy in New York. He called me at 10 p.m. on a Saturday night in response to an e-mail I had sent him and said, “You want to talk? Meet me in Little Italy now.” Our first meeting ended in the back of a bodega, with me handing Ferrara a few crisp bills as an artist’s fee for agreeing to participate in my video piece. In my mind, the work would serve as a window into the heavy mindset of two different directors at once—Pasolini and Ferrara. I went on to shoot Ferrara once a month for five months, discussing Pasolini’s death as well as how Ferrara would direct his own death scene in relation to Pasolini’s notoriously violent—and perhaps self-constructed—end. The resultant 45-minute video work of Ferrara, which has him sitting across a table from writer Alissa Bennett, who plays the proxy role of interviewer, will be presented this month as part of my solo show “I’m So Wild About Your Strawberry Mouth” at Kayne Griffin Corcoran gallery in L.A. The show is named after the German title of actor-director

Klaus Kinski’s memoir, which is a highly fictionalized account of Kinski’s life and career. It represents an extreme caricature created by one’s own hand. For me, the title conjures wine-stained lips, being intoxicated, an escape from the body, a fever dream, an altered state as location, and the sexual image of a mouth.

In my mind, what connects Ferrara to the other work in my show is the way that he has inserted and revealed himself in his more than two-dozen films throughout his career. Along with the video, I will show a series of new drawings executed on movie posters from the Emmanuelle series of erotic films. Emmanuelle (1974) characterizes a bored housewife who gets to live out her sexual fantasies through various discreet affairs. From the original film, many sequels and many posters ensued, all selling this character as a fantasy for men and women to escape into. In a sense, the films promote another type of caricature, and in a similar vein, the public knows and thinks it understands Ferrara by his films—as his films.

In my video, Ferrara can’t stop talking. His passion for Pasolini merges with his own self. It feels like a fever dream in a way. I spoke with him again over the phone this past January. He was in Paris promoting the opening of 4:44, and I was in New York finishing up new works for my show. It was nice to hear his voice again.

AÏDA RUILOVA: All right, are you ready to rock-‘n’-roll?

ABEL FERRARA: Yeah, let’s go, baby.

RUILOVA: I made a list last night of some of my favorite films of yours. I think it’s everything from The Driller Killer to Ms. 45 to King of New York to Bad Lieutenant, The Funeral, Go Go Tales [2007], and your most recent film, 4:44 Last Day on Earth. The list spans four decades—

FERRARA: I started movie shooting in the ’60s.

RUILOVA: What’s your secret to longevity?

FERRARA: The secret is good genes. It’s obviously not taking care of yourself! I feel like I’ve bent over backwards to try to kill myself. But my grandfather lived to be 96 years old. He was born in a town outside of Salerno in Southern Italy. He came to New York when he was 20. He lived in the States from age 20 to 96, but he brought his culture with him, he brought his food with him, he brought his language with him, he never spoke a word of English. My father and my uncles were born in the Bronx. They went to school, 5, 6 years old, couldn’t speak a word of English. My grandfather had 10 kids, raised two orphans off the street, and never spoke one word of English. My uncles bought him the first television set in 1947 or ’48, right? He looked at it, he went around the back of it, he took that TV and threw it right out the second-floor window. [Ruilova laughs] Brand new. But you were asking me how I managed to stick around for 40 years . . .

RUILOVA: Yeah, I mean, you created a kind of family on screen. If you put together all of your films, all the characters could be from one film, in a sense—from Frank White in King of New York to Harvey Keitel’s bad cop in Bad Lieutenant to Lili Taylor in The Addiction.

FERRARA: Those films are all made in the same period, so those are all the same kind of people, you dig? I think they are different than the people in 4:44. I guess they could be in the same family in that they’re all black sheep. The bad cop, Frank White, and Lili Taylor, those are the films about murderers, even though the bad cop didn’t kill anyone exactly—he tried to kill himself.

RUILOVA: Keitel’s character in the Bad Lieutenant is more like an apocalypse of the self—4:44 is a literal apocalypse.

FERRARA: There’s a difference between the world ending tomorrow and just drinking and drugging yourself to death. Bad Lieutenant is a guy on fire.

RUILOVA: Harvey Keitel in Bad Lieutenant is someone who is avoiding the self, and Willem Dafoe in 4:44 is someone confronting himself.

FERRARA: It’s hard to compare these guys. They’re two different people in two different films made by two different people—me then and me now. Even for 4:44, there was one guy who wrote it, another guy who directed it two years later, and now the one you’re talking to. These films are in constant flux.

RUILOVA: I feel, as an artist, that every time I make something, if I’m not on the edge, pushing myself and taking a million risks, then it’s not going to be good.

FERRARA: Why are you giving yourself a nervous breakdown? Me, personally, I don’t need to push myself. I don’t need to sharpen my own knife and slit my throat. I’m trying to chill it and find an equilibrium and a balance to my work. The pain and suffering—it’s all there. It’s there in the world, so it’s in the world of the movie. Even if you’re a poet sitting in your room writing a poem, you’re still in the world—although I guess being a poet is a different than having to deal with 40 or 50 people to raise a couple million bucks and all that bullshit.

RUILOVA: Do you feel that’s part of your role as the director, dealing with all of the bullshit?

FERRARA: You know, I’m trying to get off of that now. When I first started, I thought I was the Ringling Brothers. I thought I was Barnum and Bailey and it was the circus—we raise the money, we get the bread, we distribute the film, we take it everywhere, and eventually we make sure it’s playing to eight Eskimos in an igloo somewhere. But now I direct, and I make movies I can’t finance. I can’t raise money. I can’t sell anything, man. I make things, you dig? That’s what I do. I make things, other people sell them. If I had the money in the bank, I’d write the check for the movie, but I ain’t got it. It ain’t my thing. Right now I’m working on the Strauss-Kahn movie. My job was getting the actors, so I got them. My job is going to be to direct the film—I’m going to do it. And that’s where my job ends, you dig? I’m not going to worry what someone did yesterday in fucking Chicago or tomorrow in Paris or next year in Paris or 12 years from now on iTunes.

RUILOVA: What made you interested in focusing on the Dominique Strauss-Kahn affair?

Don’t worry about the films you’re making; worry about the life you’re living.Abel Ferrara

FERRARA: It’s Christ Zois, who’s written the script. He’s also a brilliant psychiatrist. He’s been a big help to me—in life as well as in films. But what attracted me is the event itself. It’s a Shakespeare-type deal. [Strauss-Kahn’s] wife isn’t a millionaire; she’s a billionaire. He’s the head of the IMF [International Monetary Fund]—he’s not running the grocery store down the block. It’s not like he’s got a go-go club and can’t pay the rent. He was going to be the president of France, hands down! And he gets thrown into Rikers Island. Believe me, as a white guy, you don’t want to be in Rikers Island. They stuck his ass right in the big house, baby. And when he gets out, he’s got to face a woman he’s been with for 20 years. Obviously they have a relationship that’s deep. You know, I’ve been with Shanyn [actress Shanyn Leigh of 4:44 Last Day on Earth] for seven years. You’re with a woman for seven years, it’s not just like a friendship or something; there’s something deep there. So now he’s one-on-one with this chick, and under house arrest—I mean, you couldn’t come up with this shit if you tried. Doesn’t matter whether he’s going to get off or not; he’s still got to look his wife in the eyes.

RUILOVA: You’ve worked with particular actors and writers over and over again in making your films. There must be some level of intimacy that develops over time with these people. Is there a language you’ve created from working together so often?

FERRARA: Well, what are you going to do—walk up 42nd Street and say, “Hey, who wants to make a movie today?” I work with a lot of people. I fire a lot of people. We’ve dumped a lot of people. These are the people that are left, you dig? Everyone goes in the fire, and whoever really wants to make movies is still there. Everybody wants to make movies so they can talk about making movies. But get to the 23rd hour of the 19th day—no stopping, no food, no drinking, no money, no nothing—and then you see who wants to make movies. Those are the people that you are talking about. Keitel—he’s there. You know, a lot of these guys were military guys. Ken Kelsch was in Special Forces. Keitel was a Marine.

RUILOVA: Ken Kelsch is your cinematographer. That’s an interesting relationship. As an artist, I’ve mostly made my work alone—just me and a camera in a room. I’ve also worked with cinematographers. But for me, the scariest thing is when suddenly someone else is behind the camera operating.

FERRARA: It comes back to what I was saying about how I’m a director. I’ve worked with Michael Mann, and on any given crew, he is the best cameraman. He’s also the best soundman. I know [Roman] Polanski. And on any given crew, he’s the best cameraman. He’s the best soundman. He’s probably the best editor. I’m not the best cameraman, and I don’t want to be. We all have our special gift. Filmmaking is a communal deal. What you do is a little different than what I do. You’re not making 90-minute narratives, but if you did, you’d still do it your way. I was brought up differently, so I do it my way. I don’t know if it’s because I started in a rock ‘n’ roll band and I’m leaning on all these guys . . . I don’t know, because a guy like Ken, he and I fight constantly, man. We’re at war about everything. We don’t see eye-to-eye on anything. And he’s, like, a half foot taller than me. So his entire vision of the world is absolutely different than mine, and that means a lot when you’re making movies. Ken only sees the world from a very tall person’s point of view. I hate that.

RUILOVA: [laughs] Why?

FERRARA: Because I want it eye level with the actor. I don’t want nobody looking down at my guy—and I don’t want anybody looking up at him either. I want it at eye level, motherfucker. But Kenny is something else. This guy fought in Vietnam. We were draft dodgers, but he’s the cat who brings it on. Talk about last man standing . . . That’s what filmmaking’s about. Who is going to be the last guy holding on to the moral center and moral soul of a film? Are you going to follow it everywhere, no matter what it takes, no matter who’s standing in the way, who’s dragging you down, who doesn’t get it and doesn’t see it? When you get to the finish line, man, if you’ve got five people there, you should kiss their fucking feet.

RUILOVA: I want to hear you talk about Pasolini’s death, because you’ve been writing a script for your movie about him. There are so many conspiracies around his death. In the end, it becomes a cinematic moment because the truth really doesn’t matter. It’s like one of his films, the way his life ended.

FERRARA: Yeah, because he planned it! It’s a cinematic moment because he planned his death. That murder did not happen by some 16-year-old kid he picked up, okay? Pelosi [Giuseppe Pelosi, 17 at the time of Pasolini’s murder, was sent to prison for the crime, but recanted his confession years later] had nothing to do with his murder, man, other than being there . . . Well, he did have something to do with it. He was an actor in his murder. A lot of my research is leading to the fact that Pasolini wanted to kill himself on the Sunday after All Souls’ Day, and he was going to do it in 1969, and he didn’t do it for some reason. Maria Callas might’ve stopped him—maybe. I’ve got to get all of this straight, and when it’s time to do the film, it will be straight. Right now, I’m talking a little bit off my head. In the video you and I made, I was just talking about it. But in the film I’m making, I’ve got to lay on the line exactly what I mean.

RUILOVA: I think, for me, in being able to meet with you and shoot with you and have you speak directly about Pasolini, my piece has become like a portrait of you via Pasolini. Pasolini’s films are so much about the city he’s from, about the people he’s around, and the people that are part of his life. Like Ninetto Davoli [an actor in several of Pasolini’s films].

FERRARA: Davoli is a movie in himself. Here’s a kid he picked up. Pasolini is a guy who lived with his mother, who writes a weekly column for basically the New York Times of Italy. And at 11 p.m., like clockwork, he goes to the train station to pick up an underage kid. Davoli was one of them. Then Pasolini fell in love with Davoli, but never in that bourgeois, normal-gay-guy-with-an-apartment-in-the-nice-part-of-Rome way. And then Davoli’s got to tell him, “Hey, I’m getting married, man.”

RUILOVA: And it crushed him.

FERRARA: The night he died he was having dinner with Davoli and his wife. If his fucking bathroom sink backed up, he called Davoli. He was still his guy. But I haven’t made the film yet, so I don’t know.

RUILOVA: You’ve got to make this film soon.

FERRARA: I’m trying, baby. But do you know how hard it is to raise money in Italy now? We’ll do it, we’ll do it.

RUILOVA: You’re in Paris right now for work. When are you coming back to New York?

FERRARA: I don’t want to come back to New York because, at this point, New York for me really represents the alcohol and drug life that I’m done with. There are two cities that are forbidden for me—Naples is one of them, and New York is the other.

RUILOVA: So are you in Paris now for a while?

FERRARA: I’m living a real juicy life. But we’re only here because the movie 4:44 is opening. The real deal is that I don’t want to live anywhere where I’m breathing two million cars’ fumes and paying a zillion dollars for the right to be totally hassled. Paris is exactly like New York or any city in the world. [noise in the background]

RUILOVA: What’s going on there, Abel?

FERRARA: Nothing. I’m in a house where if the washing machine shuts off, it sings a song. If Shanyn’s iPad gets a message, it sings a song. I’m living in a real postmodern time—every single thing sings to you to tell you it’s started, it’s stopped, you’ve got a message, you didn’t get a message . . . Anyway, if I do this DSK movie, it’s got to be in New York. And then I’ll have to deal with that when it happens.

RUILOVA: Let’s talk a little more about Bad Lieutenant?

FERRARA: Here’s the deal. We were talking about a movie I made 20 years ago. I don’t give a fuck about Bad Lieutenant. For me, that’s yesterday’s news. There isn’t some big board out there grading all of our movies. They’re only movies. Movies are only the result of where we are as human beings, you know what I mean? I just did an intense amount of interviews for 4:44, right? With the most intellectual, thematic motherfuckers you’ve ever met in your life, who know every film that’s ever been made—including all of my films. We can talk about Driller Killer, but I was making films for 10 years before I even made Driller Killer. I’ve been making films since I was 16 years old, man. Finally, I had to say to these guys, “Okay, let’s start from scratch.” Are we going to talk about the guy who wrote 4:44, which I was five years ago, or the guy in partial recovery who had quit drinking and was going to AA meetings but still doing heroin? That’s the guy who directed it. They were saying 4:44 was from my sobriety, but no, I wasn’t sober at all. I was high as a motherfucking kite when I directed that movie, okay? So all the shit that you now assume that this is the new straight Abel, I was just as fucked up as I ever was. Does that change the film? Absolutely not. So which guy do you want to talk about? You want to talk about Bad Lieutenant? I don’t even remember Bad Lieutenant, so that’s where Bad Lieutenant‘s at. But say you just saw The Addiction the night before . . . That’s the great thing about movies—The Addiction becomes a brand-new movie for you. You just experienced it. Lili Taylor is a 27-year-old, dynamic young actress. Do you dig? Nicky St. John [writer of The Addiction], who I haven’t seen in 15 years, wrote his greatest script the day his son died. That’s what we’re leading to. But that was like a hundred years ago for me.

RUILOVA: It’s really hard for me to look at works I’ve made 10 years ago. It’s almost embarrassing to me because I just think about how I was at a whole different place in my life.

FERRARA: Like that interview with [Quentin] Tarantino in the Times, all right? You tell me why a filmmaker is like a boxer, okay? A boxer—one split second of distraction and you could be in a wheelchair for the rest of your life. Like I told you, what’s gonna happen to you on a set, honey? Your assistant is going to spill hot coffee on your lap. How the fuck does that make you a boxer, Jack? You’re the opposite of a boxer, okay? Get it straight: You’re an artist, which is fine, man, that’s cool. But the point is, don’t worry about the films you’re making; worry about the life you’re living. You know what I mean? What is the reason and what is the purpose for this life? Like, just a few weeks ago, that dude blasted up all those fucking kids in a school, and this Buddhist retreat I go to is two minutes away from that town. I know that town. And I think we should ask people like Quentin, “How about these movies you’re making?” Some kid’s sitting in a fucking room watching one movie after another. Whether he saw these movies or not, they’re in his computer, they’re his mindset. They’ve affected the guys making the fucking computer games. Did the movies we make drive that kid to that gun? Or do the movies we make keep that kid from going to that gun?

RUILOVA: Do you really think there’s a dialogue between the two—a link between violence in film and violence in reality?

FERRARA: What the fuck you think? I mean, what’s the new Stallone movie? Fucking Shoot to Kill/Kill/Murder Me/Shoot Me/Blow Me Up/Blow My Fucking Brains Out/Kill Me, Kill You, Kill Your Fucking Mother? Come on, are you kidding me? King of New York is so lovely. We only murder every motherfucker in that movie. Because when I made that film, that’s how I felt. I felt just like that kid, okay? I was high as a kite and figured, How the fuck do I take all that anger and put it on the screen? And now I’ve got to live with that. You can talk about honesty in filmmaking. What honesty? It’s not the films, man. It’s the life you lead and the passion that you’ve got to live with. Are you driving that kid to the gun, or are you keeping him from that fucking gun? That’s the point. And these video games . . . These kids are blowing everything up. But yeah, you could take it either way. I grew up in the Bronx. I’m into rap music. I could have embraced that or embraced the other side of it, man. It took me awhile to realize that.

RUILOVA: Can I tell you a story, Abel? When I was about four or five years old, my mother drove me over to my father’s mistress’ place. It was, like, Halloween night; she put this funny brown bag over my head with holes cut out for eyes for me to peek through, and I was holding this trick-or-treat bag, like, “Yeah, okay, I’m gonna get some candy.” I wasn’t really sure where I was going or where I was being taken. She walked me to the front door and I knocked on it. This woman opens the door. She’s in the foreground, and I can see my father in the background. In the moment, I didn’t feel anything, because you’re a kid, but the situation was fucking loaded. It’s a funny image, but at the same time it’s kind of pathetic and horrible.

FERRARA: Why haven’t made a film of that yet?

RUILOVA: Oh, I did. I’ve used that story as material indirectly over the years. I have to say, there are some really insane, traumatic moments from when I was younger, and when I’ve made certain works, that’s something I’ve revisited over and over again—how to create these kinds of scenarios where there is a hyper-reality to them, because I think when I look back, “Was that real? Did that really happen?”

FERRARA: Yeah, but you don’t want to look at that thing like you did when you were a five-year-old. Picasso says, “I want to paint like I did when I was a kid.” Okay, but he ain’t painting like he was when he was a kid, you understand? Because Picasso’s also the guy that says, “I don’t seek, I find.” So the little girl that opened that door didn’t know what the fuck was going on. You know all the plays, you know all the players, you know all that’s happened, and then you’ve got to logically put that all into place. Where is that in your life?

RUILOVA: How does work overflow into your life?

FERRARA: The work is how you relate to your children, how you relate to the world, what you’re going to be. That is the fucking work. What else is there that you can do? But the question is, what are we putting out? Are we putting out dog-eat-dog violence? Or are we trying to say, “Okay, my role as human being is to try to help the pain in you.” So if you’re still holding that pain of opening that door and seeing your father with another woman, then it’s my job to think of your pain and then we should get to that pain.

RUILOVA: Now that you’ve sort of stopped with all the drugs . . .

FERRARA: I’m sober, so that’s not “sort of stopped.” I’m sober. Today, I am sober. So ask the question.

RUILOVA: Were you ever ashamed of your drug use?

FERRARA: Ashamed of it? It’s the life I lived.

RUILOVA: I know, but, for instance, in regard to your children. How does that figure in?

FERRARA: Yeah. There are things I did. What can you do? You’ve got to confront it with them. And thank god they’re still alive that I can deal with it. We can talk about it. I can deal with it. It ain’t over till it’s over.

RUILOVA: Do you think you consciously avoided discussing it for a long time?

FERRARA: Let me tell you something: Here’s the deal with drugs, man. A normal person has a problem, they try to solve it. Simplest fucking thing: You break your shoelaces, whatever. But there are no problems to an addict. You’ve got a problem, you avoid it, and then that problem gets bigger. Now that problem gets bigger, you need more of whatever you’re taking to keep you from that problem. Now that problem gets bigger, your addiction gets bigger, that problem gets bigger, your intake gets bigger. That problem never gets solved unless you stop. You dig? You can’t replace it with something. You got to stop. It took Jesus 40 days in the desert. Funny number, because it takes 40 days for heroin to get out of your body. Heroin, coke, whatever—40 days. So you’ve got to give yourself that point of unplugging from the wall and giving yourself a moment’s sobriety. And after that, if you can say, “Hey, man, I’d rather be fucked up and high and screw the world,” then hey, at least you know the person who you are. It’s not the drugs or the alcohol talking.

RUILOVA: Yeah.

FERRARA: All right, so let’s get back to the movies. [laughs] Ask me about Bad Lieutenant again.

RUILOVA: No, no. I’ve got something to ask you. I wanted to ask you about Pasolini’s hustlers.

FERRARA: He had an addiction to sex. He had an addiction to these kids. And don’t think it didn’t tear him up. I mean, he had to do it and he had to live with it. When I talk about drugs and alcohol, I’m talking about sex addiction, gambling addiction, eating addiction, throwing-up addiction. I’m not talking about mental illness, okay, although we’re on the border of mental illness. If you’re not comfortable in your own body, if you’re not satisfied by being alive, that’s a sad fucking place to be in, you dig? You know what I’m saying?

RUILOVA: How do you think Pasolini’s relationship with hustlers impacted his work—and his death?

FERRARA: I told you, he might have committed suicide. That could’ve been the last great movie of his: setting up his own death, which is a suicide. But on the other hand, he’s lecturing the world, saying, “Don’t tell me about social problems. You’re in your ivory tower of universities or government. I’m in the streets with these kids. I’m researching the problem every night.” He’s out to try to figure it all out, thinking he’s going to help these cats, you dig? On one hand, he’s ready to kill somebody; on the other hand, he breaks down. He’s a Communist, but at the same time, he’s paying poor kids for sex. Give me a break. You talk about exploitation of the working class . . . But at the same time, who’s got his arm around the kid? Who’s with him? He took those boys out of the ghetto and made them filmmakers, actors. It’s a complex issue. He was also paying these kids to have sex with him.

RUILOVA: It’s interesting because here is a director using so much power and control in his work, and then the moment he gets into his fantasy life, he trades on a different kind of power and control.

FERRARA: Yeah, but that’s all ego, man. The point is: Why couldn’t he get above that? If he was a Communist, he was a Catholic, he was a spiritual guy—why couldn’t he get beyond it? I’m not one to pass judgment. All I’m saying is, as an artist, there’s only one move to make. You’re either part of the problem or you’re part of the solution. Nobody built any hospitals with King of New York or with Bad Lieutenant. Nobody got redeemed anywhere. The guy was a drunk drug addict from the day the movie started to the minute that movie ended. There was no anything—there was no clear-minded anything—at any point in that movie. So if there’s any movie that could’ve used a sequel, that was probably King of New York.

RUILOVA: Aren’t all of your movies pretty much bad endings?

FERRARA: Yeah, especially the ones where everybody dies. I love it when they say, “Can’t you make King of New York II?” And I say, “Well, the only person that’s left is the 75-year-old lawyer. Every other person in that movie is dead. Every single human being in that film is dead.” The only one that tops that is the last movie I made, where we kill everyone on the planet. In 4:44, we kill every single human being—and not only that, but I didn’t even realize it until I was making the movie, we destroy every work of art. It’s not one of those things where, like, all the people are dead, then the Earth resuscitates and they find the Mona Lisa. No. Everything gets burned. Every work of art—all of Quentin Tarantino’s movies are dead, all of the fucking Louvre is gone, every fucking scratching on a cave wall, every little kid’s little fucking drawing of their mother and their house. Gone. Zero. That’s where we’re at. Better than King of New York, right? I’m growing as an artist.

AIDA RUILOVA IS A NEW YORKÂ?-BASED ARTIST. HER COLLABORATION WITH ABEL FERRARA WILL BE ON VIEW AT LOS ANGELESÂ?