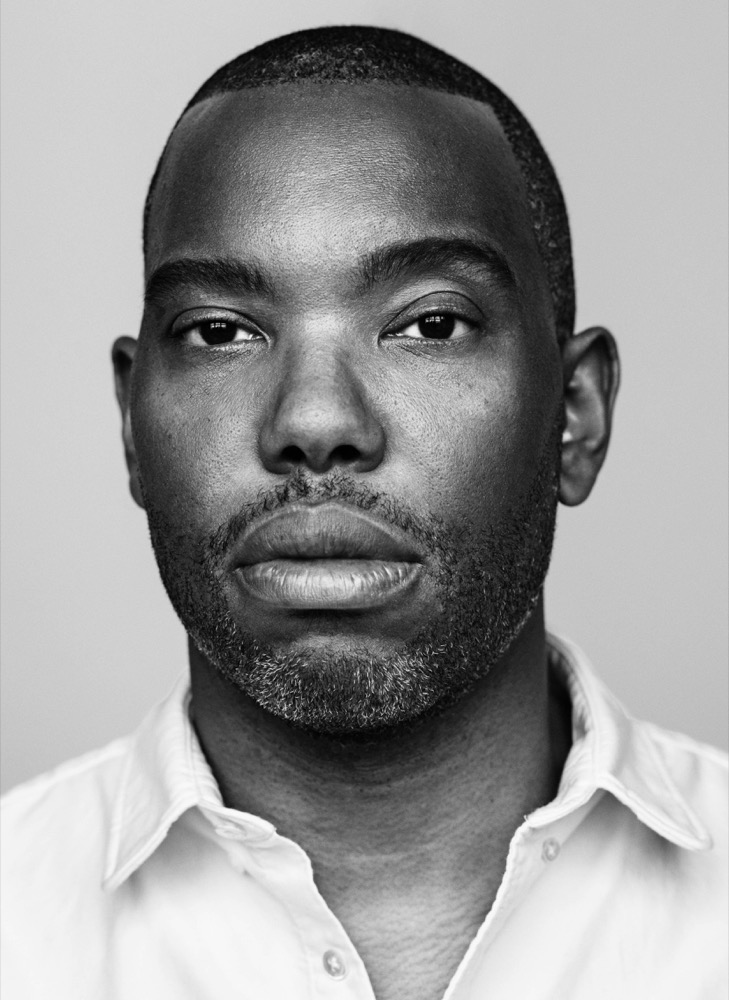

Ta-Nehisi Coates

In the early 21st century, one vocation in danger of going extinct in American culture was that of the public intellectual. Necessary voices that proved so ferocious and sobering in the preceding decades—those such as James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Gore Vidal—were beginning to be lost to the high-speed shrieks of the internet without any particular young writer-thinker gaining enough traction and gravitas to replace them. Then the very face of America promised to change with the election of Barack Obama to the presidency of the United States. Around that time, a 31-year-old black writer with a poetic prose style and a wondrously wise and curious intellect began to contribute to The Atlantic. Ta-Nehisi Coates is now best known for his wrenching examination of race in the United States in his 2015 epistolary memoir Between the World and Me. But the Baltimore native, now 42, first made his name with a series of searing, myth-shaking, rabble-rousing essays starting in fall 2007. His 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” for example, arguing for the value of the idea of government reparations to African Americans, created a lightning storm of conversations, controversies, critical reprisals, and—what Coates does so often and so well—independent thoughts and responses from all sides. These standout essays on the matter of race today are collected in Coates’s latest book, We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy (One World), with one essay for each year of the Obama administration. Far from a simple, straightforward harvesting of earlier material, Coates introduces each year and text with a poignant personal primer, writing about what was happening in both his life and in this country when he began conceiving these profiles, tracts, and treatises. The collection operates like a director’s commentary played overtop a great film, with Coates as brutally honest about his faults and uncertainties as he is about early financial concerns and his love for his wife, Kenyatta. Ultimately, these were the years, Coates writes, which took him “out of the unemployment office and into the Oval Office to bear witness to history.”

Coates, who not long ago spent a year writing in Paris, currently lives in Manhattan, and among his many projects has been writing the Marvel superhero comic book Black Panther (an ongoing series which began in April 2016). Even in the realm of fantasy, Coates is able to explore his resounding belief that, as he writes in Eight Years, “American myths have never been colorless.” Coates spoke by Skype with his friend, the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who did not let one of the most vital voices in America get off easy with his answers.

CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE: Hello, Mr. Coates. I’d like to start by—

TA-NEHISI COATES: Be gentle, be gentle.

ADICHIE: I’ve just been reading your book. I’d read many of the essays before. But this time I was thinking that it’s really a book about a writer looking back at, and engaging with, his craft. This is a book about writing.

COATES: It is, but only a writer would think that. It’s certainly the way I thought about it.

ADICHIE: There’s something quite vulnerable about it. Of course, I can say it’s vulnerable because you succeeded. Just imagine if those essays were terrible.

COATES: I had a hard time going back and re-reading a lot of the essays. I felt varying ways about them, really. [laughs] It was not a fun experience. And maybe this is true for all writers, but the work that’s closer to me in time is the work I think is better. The work that’s further away from me—the earliest work—is the worst work in the book.

ADICHIE: Which is the earliest essay?

COATES: The one on Bill Cosby. I started writing regularly for The Atlantic roughly around the time that Barack Obama got inaugurated. Every writer dreams of having the ability to hold forth for 8,000 words and pull all these different forms together: history, reportage, journalism. That was all I really wanted, and The Atlantic was my first high-profile opportunity. In those early essays, I’m just figuring out how to use it. I started off my career at an alternative paper, where I also did a lot of that. But I was young and not so good. It was a shock when I started getting big assignments. A guy called me up and said, “Listen, we want 8,000 words on this topic, and we’ll pay you $2 a word.” I said, “$2 a word? That’s $16,000!” I had to sit down while he was talking.

ADICHIE: You write a lot about being defiant. You’ve said that you don’t have faith; instead you have defiance. But in the end, you realize that even defiance won’t save you. I think your writing is defiant, and you write about white people liking your writing. The people you wrote the truth about suddenly turned around and named you as a favorite writer. I wonder how you feel about that? You know how often people of color are accused of being sellouts.

COATES: Sellout! Well, I think so much of writing is about how you deal with failure. I meet a lot of young people who have the talent and the work ethic to write. A lot of them are really intelligent and have succeeded for much of their lives. But writing is different: you have to fail in order to move forward. You can’t smart your way out of it. You can be smart as hell and it just doesn’t matter. You’re going to fail. Do you know what I mean?

ADICHIE: Yup.

COATES: I think that deters a lot of people. But even before I became a writer, I accepted the possibility of failure in my daily life. It was just the fact of my life: I could try to be a good person, but pretty much everything else that was going to happen to me out in the world was beyond my control. And it probably was not going to end too well. That was my thought. And even if that was a place I didn’t want to be, that was my home, that’s where I lived. Even after I started writing for The Atlantic, I remember just waiting for everything to go wrong at some point. And it didn’t. And it probably won’t. So what happened was, although I was very much prepared for failure, I was totally ill-prepared for success. I wasn’t prepared for masses of white people, as you say, to read my work. Now, if you write for The Atlantic, the majority of the people reading your work are going to be white. That wasn’t what I was shooting for when I set out to be a writer. When my first book [the 2008 memoir The Beautiful Struggle] came out, I drew 20 or 30 people at a reading in San Francisco, and I recall thinking, “This is awesome, this is perfect. I have a group of people who want to hear what I have to say.” Then, when Between the World and Me came out, I drew almost 3,000 people to a reading in Seattle, and that was not at all what I pictured. I know these are things that a lot of people would cut off their right arm to have, but I wasn’t prepared for it at all.

ADICHIE: I get what you mean. Success is almost accidental in a sense. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t deserved, because it’s absolutely deserved. When I think about my own writing, I don’t believe in false modesty. I work hard and I have ambition and think, “This will be a success.” But, yes, so much has to align in order for that to happen. Do you think if you had started at The Atlantic ten years earlier, you would have had the same success?

COATES: I don’t think so. I think it was the moment. This is not false modesty. I started out writing and studying poetry at Howard University. To this day, some of the work that moves me the most is poetry, which most people don’t care about. I don’t think the power of something moving is necessarily tied to 2,000 people showing up to see you.

ADICHIE: Certainly you haven’t changed your approach to the truth based on the fact that The Atlantic is read more by a white audience. You have a truth that you’re looking for and you’re so focused on finding it. Sometimes that makes people uncomfortable—even liberal people.

COATES: You know, it wasn’t white people who first caused me to realize that this was a problem; it was black people, when Between the World and Me came out. Cornel West wrote a blistering Facebook post about it and about Toni Morrison’s endorsement. And then the pace picked up. A certain number of black folks in the academy came out attacking the book. I couldn’t figure out why, because I had been writing that very same way for about seven years. It wasn’t like I was all of a sudden saying anything differently. And in fact, a great deal of what I was saying was based on work that had been done in the academy. What eventually became clear to me was that there was always this undercurrent in the criticism of me representing the white people’s go-to guy. White people want to get over doing something about racism by reading Ta-Nehisi Coates. That was always the critique, and that’s when it started to bother me. When only a few people were reading me, no one really cared. But in this culture, the attention of white people is a kind of currency. And I never intended to become that one voice. I think the whole idea of the one voice is reflective of a kind of racism in the culture. But people might think it anyway: “That’s who you are now, whether you want to be that or not.” And it’s one thing for white people to say that, but to see black people backing it up … it was like, “Shit, man.” It put on another level of pressure. I think if I were trying to be a healthy writer, I would not read any of that stuff. Do you read your reviews?

ADICHIE: No. I just don’t. And trust me, when you don’t read two, then you don’t read four or six. It becomes very easy. It’s self-preservation. It messed too much with my head.

COATES: You don’t check your book sales at all?

ADICHIE: I can’t tell you how many have sold, but I’m very happy whenever I get the direct deposit [laughs] … Anyway, let’s talk about your father. I love your dad.

COATES: He’s my harshest critic. He likes this book better than Between the World and Me. Only he would like this better than that one.

ADICHIE: Why did your father make you fast on Thanksgiving as a boy?

COATES: My dad was in the Black Panther Party.

ADICHIE: And a vegetarian?

COATES: Yes, but he eats fish. I’m going to try to get this story right: When George Jackson, a Black Panther, was killed in prison in California, folks in the prisons protested by fasting on Thanksgiving. In solidarity, a bunch of folks out in the community also fasted. This went on for three or fours years. By the time I was aware of it, my dad was the only person doing it. [Adichie laughs] But then it became this thing about being reflective on the Native Americans. And it’s really profound if you think about it, because Thanksgiving is such a day of gluttony. My dad talks about that, the gluttony when we sit back stuffing ourselves as much as we can and watching this one sport, which I love, but which we all now know is destroying people’s brains. That might have been one of the smarter things my father did.

ADICHIE: [laughs] There’s a romance, though, to being raised by a father who’s a former Black Panther and a vegetarian, who is making you fast and read certain books. Do you see that?

COATES: No, I hated it. I just wanted to be American when I was a kid. I just wanted to be normal, like the Americans I saw on TV. I was like, “Who would name their kid Ta-Nehisi? Who would do that to their kid?” [both laugh] No one could ever get it right, and still no one can. It’s like it’s intended to be mispronounced and made fun of. And they sent me to public school in inner city Baltimore like that!

ADICHIE: Okay, so I have a note here that I made about this idea of yours about Obama being a kind of second Reconstruction. Tell me about that.

COATES: I’m just going to be honest with you; there are many aspects of the book. This is probably the least exciting aspect. I think the comparison is interesting, but I don’t think I spend much time on it beyond the introduction. I think there’s always been this basic sense among black people that if we show white people that we can live by middle-class American norms, that we are actually good people, that we aren’t monsters, then a critical mass of white people—not all white people and maybe not most white people, but a critical mass of white people—will therefore be convinced of our worthiness and the gates to the bounties of America will open up to us. It’s implicit in the civil rights movement. It’s implicit in the Harlem Renaissance. It’s implicit in the title of the book, which is taken from words spoken by a congressman in South Carolina who lists all of these great things that black folks did for the government and can’t fathom why these white people want to strip black people of their rights. What he didn’t understand was that the only thing South Carolina feared more than a bad Negro government was a good Negro government. You following these middle-class norms is exactly what they hate the most because it screws up the machinery. And I think for the past eight years, Barack Obama was a walking advertisement for that fact. I mean, here’s a guy who had the most traditional of families—married to a woman, two kids, a dog named Bo. [laughs] He was just the most bourgeois, and I don’t mean bourgeois in the derogatory sense. I mean, if you were to imagine an American family, that’s what you would imagine. They could have been a TV show, man. And still, they got postcards with watermelons on the front. By the end of his time in office, well over half of a major political party believed that this guy could not be American. My argument is that it was this very bourgeoisness that made people feel that way. In the book’s introduction I have this quote from the Civil War, when black people had started fighting for the Union and had proven themselves in battle against the Confederates. And the Confederates say, “Listen, man, I know we don’t like these niggers, but they’re fighting well over there. So maybe some of them should fight well for us?” And the guy says, “You can’t make slaves into soldiers and enslave the soldiers. Then our entire theory of slavery is wrong.” In other words, if people who we considered to occupy this particular place in society are capable of being courageous and capable of fighting—if they’re capable of being men in the sense that we construct men at this time—then we can’t have slavery. In order to have slavery, we have to have them play their role. And it’s the same thing here.

ADICHIE: But hold on. With Obama, I get the bourgeoisness. I mean, Obama was the perfect magical Negro. But would he have been elected if he weren’t?

COATES: No, you’re exactly right. That’s the only way he could have gotten in there. And then he was hated because of that. That’s exactly what I would argue. Because of where the country was in 2007, 2008—two failed wars, economy in the toilet—people thought, “Okay, maybe we’ll try this guy.” But once everything got fixed …

ADICHIE: I know this is chutzpah, and maybe I sound like your dad, but the time to let the black guy win is when everything goes to hell.

COATES: My dad said it much more profane than that. [laughs] Honestly, I don’t want to overgeneralize. There are a substantial number of white people who just straight voted for him because they think he’s the best guy. But there’s still that core who thinks, “Okay, when they’re adhering to bourgeois norms, that means I might have to compete with them for that middle-class job. They might be my supervisor.” It destabilizes a system that’s been in this country since its conception, going back to Colonial times. Look, we were eight years in power. This guy had a scandal-free administration. And the response was to elect Donald Trump.

ADICHIE: I can’t understand it. Are they just being reactionary?

COATES: Not only that … You have Martin Luther King Jr., right? He was out there preaching nonviolence. And the response was to bug his phone and then to shoot him. He was the nicest, most palatable sort of example of a black man, and the response was violence. I talk about this in the epilogue. Excuse my language—”If the nigger can be president, then I can be president, too.” Any white person can be president. Any one of them would qualify. Trump is the first president to serve in office who has no public sector experience at all: never been a politician, never served in the Army or anything. I could be wrong and maybe historians will get on me about this, but I don’t think there’s been anybody else with such complete ignorance of how government works. This is remarkable. But it’s not remarkable if you take white supremacy as the starting point. It then begins to make a bizarre, deeply depressing kind of sense.

ADICHIE: What sense do you make of people who voted for Obama and then for Trump?

COATES: I think it proves the racism. On one hand, you have an Ivy League-educated lawyer, the first black editor of the Harvard Law Review. Obama didn’t have three wives like Trump. He couldn’t have bragged about sexual assault. The question isn’t, “Did you vote for Obama and then vote for Trump?” The real question is, “Would you vote for a black Trump and then vote for Trump?” That’s the actual question.

ADICHIE: That’s true, actually. While Obama was president, I just felt so protective of him. But in your essays, you’re harsh on Obama, too. Looking back, do you think that your criticism of him was fair, considering everything?

COATES: I didn’t take any pleasure in writing that. Those were hard pieces for me to write. Can I ask you something? Does it mean anything to you that his father was African?

ADICHIE: I think of Obama as an American. I don’t think it changes my admiration. I just love him. Maybe if I were Kenyan that would matter more. By the way, when are you coming to Nigeria?

COATES: I don’t know. When am I coming to Nigeria?

ADICHIE: [laughs] Make your flight out to Lagos.

COATES: I want to come. I want to talk about my comic book in Africa. I’d love to do that.

ADICHIE: I’m sure you would have tons of people turn out. I wouldn’t be there, though. I don’t really care for comic books.

COATES: [laughs] You don’t like them?

ADICHIE: Sorry, I have no interest.

COATES: I’m going to make them interesting for you. Just listen for a second about the one I write. The guy’s name is the Black Panther. He’s literally called the Black Panther. All right?

ADICHiE: Maybe you should talk to my brother about comic books. I had no idea you were doing them until he told me. I was like, “Wait, what?”

COATES: No, let me tell you! It’s pertinent to our conversation—if you’ll let me tie it together. The Black Panther was invented by two white people in the 1960s during the civil rights era, and none of their superheroes were black. So they invented this guy who’s the king of this mythical African country called Wakanda. Wakanda is the most advanced civilization, not just in Africa, but on the entire planet. And unlike the rest of Africa, Ethiopia excluded, it has never been colonized. I find Wakanda and the Black Panther so fascinating because what I actually think it comes out of is the need or the desire among black people to have a home. And to have a home that’s not built on Western European values but that still measures up in all the ways they’ve been told they’re inferior. And even though it wasn’t originally written by black people, the root of it is the African American projection of Africa in a mythical sense—frankly, in the way that I grew up with Africa, the way Africa existed in my household and in the Afrocentric imagination that was all around me. It was a mythical, created past. White people create their past, too—let’s be really clear about that. This wasn’t any different.

ADICHIE: So basically it’s a Kwanzaa comic book.

COATES: Do you celebrate Kwanzaa?

ADICHIE: No. [both laugh] My second-to-last question involves this line I underlined, “protest to production,” when you talk about how African Americans should move from protest to a real engagement with the history of the Civil War.

COATES: That sounds kind of arrogant. I’m sorry I wrote that.

ADICHIE: [laughs] Well, I was thinking about it in terms of all those beautiful statues of beautiful men that people want to take down in America right now. Do you think those Confederate statues should come down?

COATES: Yeah, I think it’s awesome. It’s high time. There’s this perception that things just started this year with Charlottesville, but black people have been going after that stuff since it went up. I know a lot of people feel like it’s placing symbols over substance. But I really think they’ve got it backwards—symbols have substance. I know we like to think that if we have our facts straight and have a well-documented argument, it will change people’s minds, but it doesn’t. Facts are overrated. I mean, they’re important. We need to know what happened. I’m a journalist and I rely on facts all the time. But as Hollywood shows us, you really need to build a story, a narrative. I’m not saying this to flatter you, but novels are more important right now. Books and stories shape conversation, they shape the imagination. That stuff is terribly important.

ADICHIE: Okay, but you dodged my question about lecturing black people on moving from protest to production. I want it noted that you dodged that question about lecturing black people.

COATES: [laughs] Okay.

ADICHIE: My last question is about love. I’m such a hopeless romantic, and I just found it so lovely when you write about you and your wife, Kenyatta, where you describe hearing someone talk about what they want to become and then seeing them become that. I had to stop myself from crying. The question is: Are you afraid of being sentimental?

COATES: Yes, I’m afraid of being sentimental. I’m not afraid of writing romantically or writing about love. But it is hard to write about love without being sentimental or maudlin. If I write about love, I want it to have the same power and force as everything else. And that was the hardest part of the book to write about. I’m actually a hopeless romantic, too. I liked your novel Americanah largely because of the romance. Did you read a lot of Jane Austen?

ADICHIE: I used to.

COATES: I wish I could write like that. Also, The Age of Innocence, by Edith Wharton, gets romance right. It gets love right and it’s grounded and it’s beautiful. It’s deeply moving.

ADICHIE: Are you working on writing fiction?

COATES: I am.

ADICHIE: How’s it going?

COATES: I’m not working on it right now. It’s very sad.

ADICHIE: Well, if it helps, you’re not ever alone in that space of frustration and wanting to write.

COATES: Your misery doesn’t make me feel better but …

ADICHIE: [laughs] It’s not meant to make you feel better, just to make you feel less alone about it. It’s been very nice talking to you. I’d also like it noted that I actually kind of like you now, but I didn’t when I first met you.

COATES: [laughs] And I want it noted that I always liked you, Chimamanda.

CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE IS AN AWARD-WINNING NIGERIAN AUTHOR. HER MOST RECENT BOOK, DEAR IJEAWELE, OR A FEMINIST MANIFESTO IN FIFTEEN SUGGESTIONS, WAS PUBLISHED IN MARCH.