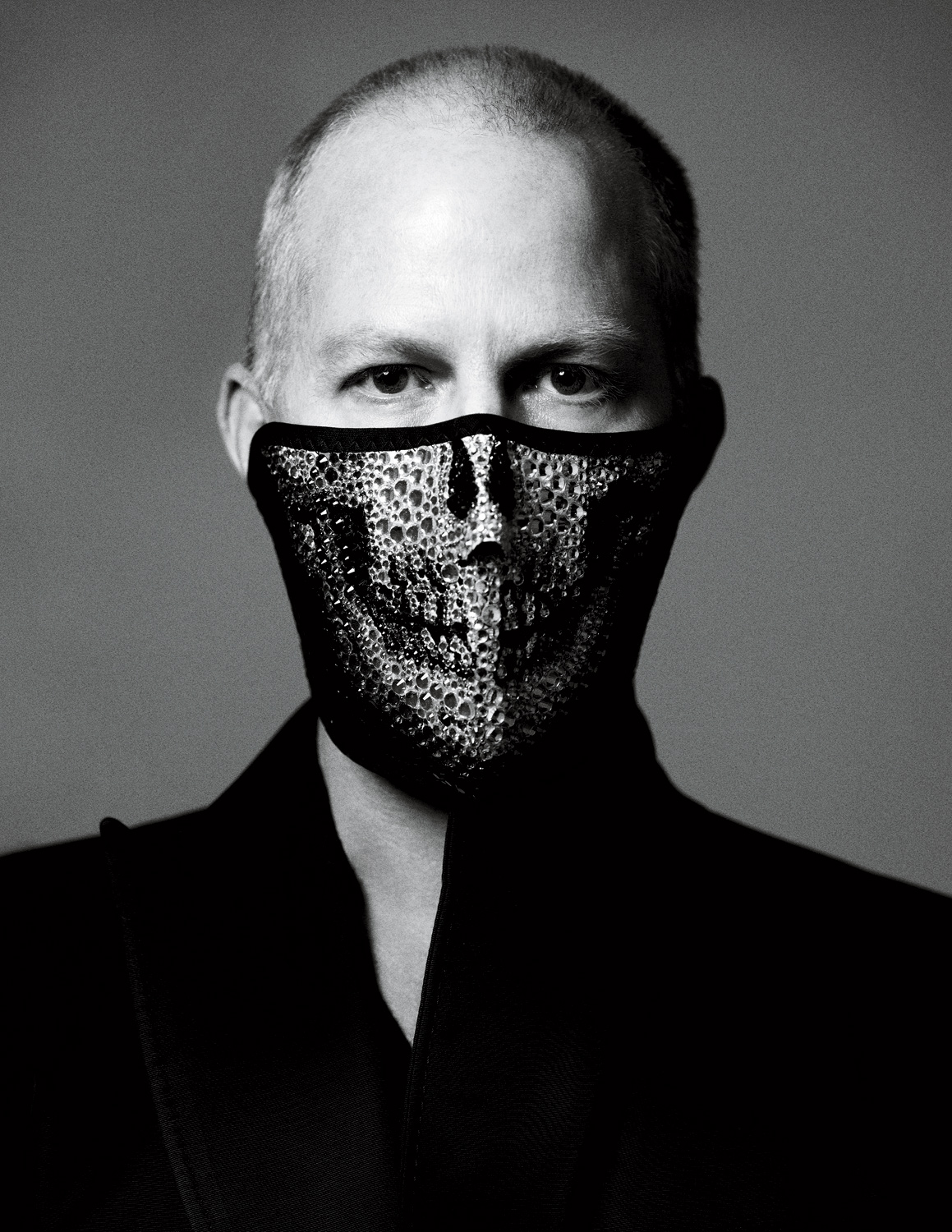

Ryan Murphy

i was like ‘I can’t write any more nice speeches for these Glee kids about love and tolerance . . . .I’ll kill myself.’Ryan Murphy

With his hit Fox show, Glee, and his newer FX serial, American Horror Story, writer-producer-showrunner Ryan Murphy has managed to transform quirky preoccupations with earnest underdogs and old-school haunted-house ghouls (respectively) into two of the most successful, distinctive—and in many ways, unlikely—TV phenomena of this young decade. On Glee, a group of teenage outcasts at William McKinley High School in Midwestern Ohio band together to face down their slushie-throwing oppressors and belt their little hearts out to retooled, choreographed versions of songs by everyone from Barbra Streisand to Lady Gaga, Journey, and Beck. The show’s triumphant rise since it debuted in the spring of 2009 has not only adrenalized the careers of its stars—in particular, Lea Michele and Jane Lynch—but also snatched up four Emmys and four Golden Globes, including the prize for Best Television Series, Comedy or Musical two years running. In the process, its musical repertoire has also become a Billboard chart–dominating cash cow, with more than 12 million Glee cast albums sold worldwide. It’s even spawned the Murphy-judged Oxygen reality spinoff, The Glee Project, in which contestants compete for a role on the show. But while Glee has been busy untangling tuneful, socially responsible adolescent drama (bullying, teen pregnancy, sexuality), Murphy’s more recent offering, the FX freak show American Horror Story, is fixated on other, more prickly subjects—among them, S&M fetishes, dismembered babies, and the myriad difficulties that come when one cohabits with the irredeemably pissed-off undead. American Horror Story tells the tale of an unsuspecting, on-the-rocks married couple, Ben and Vivien (Dylan McDermott and Connie Britton), and their angst-ridden daughter, Violet (Taissa Farmiga), who move into a cavernous and ominous-looking house in Los Angeles only to discover that it’s crawling with nefarious spirits, besieged by meddling neighbors (including a washed-up, failed actress played by Jessica Lange), and terrorized by a creature known as the Rubber Man, a masked, latex-sporting demon who slips into Vivien’s bedroom one night and impregnates her.

Murphy, 47, grew up in an Irish Catholic household in Indiana, and started out his career as a journalist, moving into writing and producing in the mid-’90s. His first foray into television, the short-lived but critically acclaimed series Popular, ran on the WB Network from 1999 to 2001, and, like Glee, offered a self-aware examination of high-school social dynamics—in the case of Popular, through the lens of a cheerleader and would-be journalist who are forced to become cordial when their parents get together. His next series, Nip/Tuck, which ran for six seasons on FX, proved darker and more warped, centering around the occasionally shifty practice of two plastic surgeons in Miami (and, in later episodes, Los Angeles) whose difficult personal lives often become entangled with those of their patients. He has also directed two films, both adaptations of best-selling books: Running With Scissors, based on Augusten Burroughs’s memoir about being sent by his mother, who battled depression, to live with her psychiatrist and his eccentric family; and Eat Pray Love, based on Elizabeth Gilbert’s self-exploratory travel tome about the globe-spanning trip she took following the dissolution of her marriage. In addition to Glee and American Horror Story, Murphy is also at work on a forthcoming half-hour comedy for NBC about the relationship between a gay couple and the surrogate who is conceiving their child, and he’s also signed on to direct a movie adaptation of Larry Kramer’s Tony Award–winning play, The Normal Heart, which centers on the AIDS crisis in early-’80s New York City.

Julia Roberts, who worked with Murphy on Eat Pray Love, recently caught up with him in Los Angeles.

JULIA ROBERTS: I remember when we first met like it was yesterday. I remember the sunglasses you were wearing, the hat you were wearing. You had on a baby-blue hat—and you’re not a hat guy.

RYAN MURPHY: But I wore one today. I only wear hats when I meet you, apparently. I remember I was nervous to meet you, but then within two seconds of sitting down, I wasn’t nervous anymore. You and I talked about baby allergies for, like, 20 minutes, which is a weird intro.

ROBERTS: Oh, right! Henry [Roberts’s son] wasn’t supposed to eat purple things.

MURPHY: Purple and red. I was besotted. I feel that our relationship since then has been exactly the same.

ROBERTS: I do, too. All right, let’s talk about a television show that I like to call “The Show I Can’t Even Get Through the Commercial For.”

MURPHY: American Horror Story?

ROBERTS: Yes, the poster for it was . . . crazy.

MURPHY: Well, I guess, like all my TV shows, it’s rooted in a childhood obsession. Two actually: Dark Shadows and a movie called Don’t Look Now [1973], with Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie. The thing on the poster is Rubber Man. He’s a monster in the show, and he dresses up in latex, and he’s supposed to represent every woman’s deepest sexual fears and desires. What I really wanted to do was my version of Dark Shadows, where there are creatures and a soap opera and sex, because my grandmother used to make me watch Dark Shadows as punishment . . . when I was three.

ROBERTS: When you were three?

MURPHY: Yes. I would sit there and be very afraid, and then the next day I would say, “Nana, I want to watch the program again.” I would call it a program. I would hide behind the chair. I just loved feeling scared.

ROBERTS: See, that’s the thing. You can divide the world into two groups: people who like to watch things and get scared, and people who don’t.

MURPHY: Yeah. But, my grandmother . . . This was the woman who’d take me to the mortuary. We had a large family, and every week there was a death, and she would make sure that she and I were the first to the mortuary. She’d make me go up and touch all of the dead bodies so that I could learn that they were gone and that was formaldehyde used on them. That’s my life. You’re freaked out right now.

ROBERTS: I’m just thinking about my grandma right now. Just thinking about her big butter biscuits.

MURPHY: And then there’s my grandmother with her black tar coffee and obsession with morgues.

ROBERTS: But you know what’s nice? I like the balance you’re creating for audiences, consciously or unconsciously, when you do a show like Nip/Tuck—which I was a fan of until I couldn’t take it anymore—and then a show like Glee. And now you’ve done this.

MURPHY: I think I have a pattern of nice and lovely and then dark and twisted. But I’m attracted to that. Also, American Horror Story came about because I was like, “I can’t write any more nice speeches for these Glee kids about love and tolerance and togetherness. I’ll kill myself.” So then I was like, “I’m going to write a show about anal sex and mass murders.”

ROBERTS: Shhhh!

MURPHY: Just kidding. We don’t really do that. But I think as an artist sometimes you want to do the opposite of what you just did.

ROBERTS: Yeah, I think unconsciously you do. Also, you’re going through a really happy period in your life right now, which maybe makes you want to do dark things in your work.

MURPHY: Yeah, at home it’s all moonbeams and puppy-dog tails, so I guess I do have a darker side—and I like writing about it.

ROBERTS: You started out as a journalist and then transitioned into tv and film.

MURPHY: I had been accepted to film school, but my parents couldn’t afford it, and yet they made too much money for me to get a scholarship. I couldn’t go to USC [University of Southern California], which is where I was supposed to go. So I moved to L.A. I was dating [director] Bill Condon at the time, and I lived with him through most of my 20s. I wrote for Entertainment Weekly and the Los Angeles Times. Then we sort of broke up around 1996, and I wrote a script basically about that breakup called Why Can’t I Be Audrey Hepburn? It was a really sweet romantic comedy.

ROBERTS: I wanna read that script.

MURPHY: Steven Spielberg bought it and was going to make it. It was one of those projects where every huge wonderful actress in the world was either interested or attached, and finally, after two years, I got it back. I could have gone on a different path. I could’ve done that rom-com girl “hats and pumps” thing. But as a writer, I got really frustrated with film development, which of course you would. So I sold a TV show a year and a half later called Popular, which ran for two years. Then came Nip/Tuck.

ROBERTS: I’m so glad your Audrey Hepburn movie didn’t go or else you would’ve been impossible. You just would’ve been sassy. We wouldn’t have gotten to be friends.

MURPHY: Maybe . . . I remember being so devastated that it didn’t go. I was like, “My world is over!” It was so close so many times, and I so wanted my first big break. But you know, just the other day I told a young writer who did a TV show that just got cancelled, “Listen, here’s a thing you won’t know at 30 that you will know at 45: Every failure or miss or moment where you’re like, “Why is my world ending?” leads you to your success.” I know it’s corny to say, but it’s almost like your path is predetermined. The failure of that script led to my first big break.

ROBERTS: I love that. You have to suffer through it because if it comes easily, then you’ll think it’s easy.

MURPHY: Did you have that as a young actress?

ROBERTS: What? Rejection to fuel my passion? Abundantly.

MURPHY: Did you?

ROBERTS: Of course! I never got on the show Vegas, which I auditioned for almost weekly. It was my dream . . . So, you said Nip/Tuck was your big break. That was on for a long time.

MURPHY: Seven years, 100 episodes, I think.

ROBERTS: Having to keep coming up with situations and scenarios and dialogue, how do you stay interested?

MURPHY: I think you don’t, really. That’s what I’ve learned. After more than four or five years with a show, I think you have to move on or sort of train someone to see things like you see them. Tone is everything in TV. I would hand it off to somebody else, but I would stay involved. I also believe in bringing a lot of young people up and giving them their first breaks.

ROBERTS: Like [Murphy’s collaborator] Brad Falchuk. Tell me about him.

MURPHY: The story is, I was interviewing writers for Nip/Tuck, and little Brad Falchuk was on his way to an interview for the TV version of Tarzan. He was so young and as soon as I met him, I just loved him. His mind works in a very similar way to mine, but very differently. We’re like brothers. He created Glee with me and Ian Brennan, and he co-created American Horror Story.

ROBERTS: You and Brad and Ian—you’re like a threesome, right?

MURPHY: Well, like we say, I’m the brains, Brad’s the heart, and Ian is the funny bone. I think we all have an affinity for different characters. Ian writes almost every word of Jane Lynch’s character on Glee. I tend to be the person who walks in and says, “I’m really interested in the color purple and the color orange. We should do tributes to those colors.” It makes no sense. Like, you know, with American Horror Story, I was like, “Why can’t the Black Dahlia be a patient of Ben [played by Dylan McDermott]?” I’m somebody with a lot of different obsessions, and I like to put them in my work. That show is about our fears, too. You remember that case in Connecticut about the home invasion? I’m terrified about that, so we did an episode about it. What would you do if somebody was in your house?

ROBERTS: It’s too scary.

MURPHY: Too scary. Lady, this is not a show for you.

ROBERTS: It’s not. I can promise you I’ll never watch it.

MURPHY: When you were a girl, did you see The Shining [1980]?

ROBERTS: No. Too scary for me. I didn’t see The Exorcist [1973] until I was 22. I’m the kind of person who will sit in a movie, and when something scary happens, I will absolutely scream out loud. The last scary movie I saw . . . I want to say there was a moment I was screaming. I was clutching Danny’s [Moder, Roberts’s husband] arm, and he finally turned to me and said, “You have got to stop!”

MURPHY: What was the movie?

ROBERTS: This Spanish movie, The Orphanage [2007]. It scared me witless when the old lady is pushing the pram and they stop and then she gets hit by the bus. [laughs] I was on the ceiling.

MURPHY: I want to go see a scary movie with you now. So you don’t have a favorite scary movie?

ROBERTS: No, I hate them all equally.

MURPHY: So there goes my dream of writing The Exorcist: Part IV for you. I think people think I’m cynical and dark, but you know me—it’s not true. I think the key to success in television is to do something that either nobody has tried to do or to reinvent a genre that has not worked or is dead. And both Glee and American Horror Story do that. No one has ever tried—well, they’ve tried—but no one has ever done a really big musical on TV that worked. And people have done great horror shows, but they’re the kind of horror shows that I grew up with, like Dark Shadows or Kolchak: The Night Stalker. With Glee, I went into a meeting at Fox and said I wanted to do a musical, and they kind of laughed, and I said, “No, I really want to.” And they asked how, and I said, “I don’t know, but I think it has to be smart and postmodern.” Then, as if I conjured it from the heavens, two days later I was in a gym, and this guy came up to me and said, “I don’t know you, but would you read this script? I’m producing it.” It was a movie script Ian had written called Glee, and it was very different from the show. The teacher was, like, a crystal meth addict and I think people were disemboweled. But I was like, “Oh, high school kids doing Beyoncé songs as opposed to all gay show tunes? That makes sense.” So I called up Ian and he said, “Yeah, I’ll turn that into a TV show with you and Brad,” and that was it.

ROBERTS: That’s how you met Ian?

MURPHY: Yeah. I was just handed his script. I was in a towel. I was heading to my locker after working out. So I put it out there, and then it came. I do believe in that.

ROBERTS: How do you pick the songs for Glee? How do you get all these big songs on the show?

MURPHY: It’s always been very blessedly easy because right at the start people liked it. I think they also knew it was about kids—it was about arts education. “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” was one of the first songs used, and Steve Perry was one of those guys right from the beginning who said, “Let’s try it.” I got great artists right away: Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger. I have very schizophrenic music tastes. I love a good Barbra [Streisand], I love a good Rolling Stones. I grew up loving music. I choose all the songs, and sometimes they’re fantastic, and sometimes they’re, like, eh, but that’s the process. I think we have a pretty good batting average. We’ve sold, like, 38 million singles and 12 million albums worldwide. My favorite is when we do mash-ups, like pairing Lady Gaga’s “Yoü and I” with a song from 1982 called “You and I” done by Eddie Rabbitt and Crystal Gayle, which I know you know. It was my prom theme.

ROBERTS: [sings] Just you and I . . . So what’s your Holy Grail of guest stars for Glee?

MURPHY: Julia Roberts and Javier Bardem! No, I get asked that every week, by the way.

ROBERTS: About me being on the show?

MURPHY: And I’m like, “She’s never gonna be on the show. Just face it.”

ROBERTS: Somebody told me Lea Michele said that I would be her dream.

MURPHY: I got so much shit last year for having a lot of guest stars, so this year we’re not doing it as much—although Gwyneth [Paltrow] came on and won an Emmy, so that was thrilling. Who do I want to have on? I think Keith Richards should come on.

ROBERTS: That would be funny. How do you figure out how to divide your time between Glee and American Horror Story? That has to be the challenge now.

MURPHY: Yes, it is, but I love that. I work in the morning with the Glee people, and then I work in the afternoon with the Horror people, and then I go back to one of them later—like 6 to 8 at night. I work all weekend . . . But that’s the gig, and I have a supportive partner, thank god. I get really bored if I’m not doing a lot of things . . . It’s schizophrenic and the shows are so incredibly different, but that keeps me on my toes.

ROBERTS: You’ve also directed two movies, Running With Scissors and Eat Pray Love.

MURPHY: Yeah, and I’m getting ready to do a third, The Normal Heart. With the first movie, it was a case of me reading a book and really relating to it. I love Augusten Burroughs [whose memoir, Running With Scissors, served as the basis for Murphy’s film]. I think that movie, though, was problematic, because I was madly in love with Annette Bening and her character, and the story was about the boy. I clearly wanted to deal with something in my own life. That film was the kitchen sink. I was like, “Wait, I can get all these great people and meet them.” I was young. But movies to me are about learning things, and I learned a lot from it. Eat Pray Love—you know, I wanted to do that with you, and we had a ball. I feel like TV is my main gig and the movies are my hobby. So I’m doing The Normal Heart, and after that, an alien/monster movie because I’m interested in those. I love them. I think movies come to you to teach you something that you need at that point in your life.

ROBERTS: I think there’s always timing involved.

MURPHY: Timing, yes. Otherwise, I never would’ve traveled around the world—particularly to India with you in the 120-degree heat. That’s why we’ll always be friends. We survived India in September—although, you were much better at it than I was.

ROBERTS: Do you have a structure to your writing? Like, do you write from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. every day?

MURPHY: No, I don’t write regularly, particularly on the TV shows. I have to muse on something for a really long time. I’ll think what the episode is about for a week or two, and then it’ll just explode out of me. It feels like some power, almost like you’re channeling something. It’s weird. I can’t explain it. But I kind of don’t want to know. I just feel like I’m open, and I let things come in. A lot of people are going to sit down from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., and then they’re lucky if they leave with four pages. I would kill myself. I just have to think and think and think, and then I wake up in the morning, or I’ll be driving, and there it will be. Also, I think that good writing is rewriting.

ROBERTS: Do you ever take a day off?

MURPHY: Yes. I will take off the occasional Sunday. It’s been hard because of the two shows. I’m not good at vacations. I think some of it is that I have a fear that the opportunity is going to be taken away.

ROBERTS: What are you going to do with Glee, because these children will grow up . . .

MURPHY: I don’t know. So many of the kids that I’ve lived and breathed for are graduating at the end of this year, so it’s like, “Do we do another show? Do we spin it off? Do I stay with this show?” I don’t know what I want to do. What I really want to do is open a restaurant. I want to give up the cruel mistress of showbiz.

ROBERTS: Well, Hazel [Roberts’s daughter] always tells me that if I want to get a job, I could probably get a job as a cook in a restaurant, so I’ll come cook for you.

MURPHY: I want it to be really cozy, like something that would be in Big Sur. But I don’t really want to cook. I just want to decorate it.

Julia Roberts is an Academy Award–winning actress