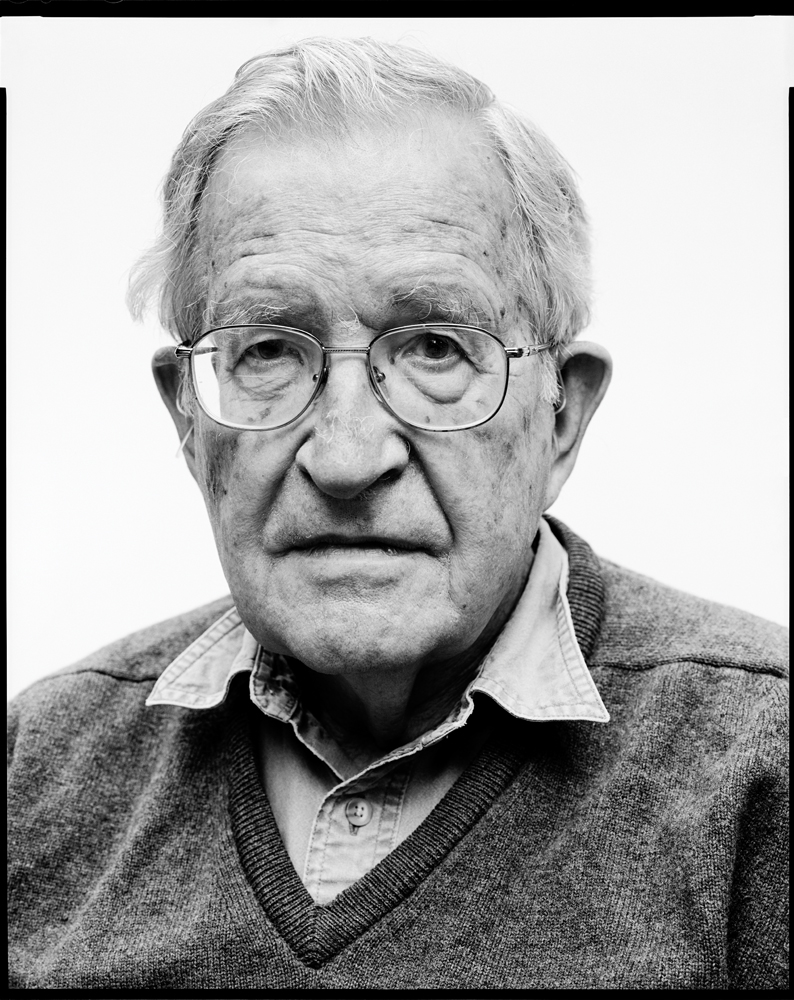

Noam Chomsky

I presume that each of us has the capacity to be a saint or a monster. The rest is up to us. Noam Chomsky

In his address at the United Nations General Assembly hall last October, Noam Chomsky began by saying, “Many of the world’s problems are so intractable that it’s hard to think of ways even to take steps towards mitigating them.” Considering that Chomsky was invited specifically to discuss the ongoing and steadily worsening conflict in and around Gaza and the West Bank, the assembled body probably thought they knew where he was going. But Chomsky, never one to accept the accepted thinking, said instead, “The Israel-Palestine conflict is not one of these.”

If this seems contrarian or provocative, it is business as usual for the ferociously independent-minded Chomsky, high priest of the American Left, activist, soothsayer, and oracle for generations of progressives. Born in 1928 and raised in Philadelphia, where his father was a Hebrew scholar, Chomsky took his baccalaureate, Master’s, and PhD in Linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania. In 1955, fresh out of school, he immediately began teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and simultaneously began revolutionizing the fields of linguistics, cognitive science, and the philosophy of the mind with several of his now eponymous theorems. (I won’t even attempt to relate them here, but suffice it to say that Chomsky’s stature in the field of linguistics is roughly akin to that of Stephen Hawking’s in physics.)

And until about ten years ago, when he slowed down his classroom schedule, teaching and writing about topics like generative grammar and analytic philosophy has been his day job. But from at least 1967, when his essay “The Responsibility of Public Intellectuals” appeared in The New York Review of Books (calling members of the media and academe to task for their habitual cowering to and championing of the policies dictated by governments), Chomsky has been the de facto conscience of the Republic, our premier critic of imperialism (American and otherwise), calling out the ills inherent in systems of power and privilege with an elegant ease and unparalleled clarity. Whether he is debating, say, Alan Dershowitz in one of their great tête-à-têtes, or riffing before an auditorium of dignitaries, giving a commencement speech, or writing one of his scores of books, it can seem as if Chomsky has the entire matrix of human scholarship at his ready recall, summoning quotes from Hume to the latest Human Rights Watch statistics to support the point he is then making.

But if the truths he speaks to power do seem to be glaringly apparent to him (for instance, that the aforementioned Israel-Palestine situation could be solved, according to a peace proposal presented to the U.N. in 1976, and it is merely the patently racist and opportunistic expansionism of Israel, supported, in every sense, by the United States, in contradiction to nearly universal opinion and the Geneva Conventions, that is responsible for the continuing horror there), he never grows disappointed in or frustrated with the rest of us dullards to whom he must explain it all. His patience, concern, and engagement are peerless, but Chomsky would be the last to ever act the guru. Nor is he dissuaded from his work (nor, somehow, astoundingly, is he disenchanted with the entire human endeavor) even after more than half a century spent in close consideration of the most hideous acts of man—from commonplace villainy to global, industrial-scale atrocities. As he explains in his recent collection, On Anarchism (New Press), both of these things, the unswerving optimism and dedication, like his detestation for hero worship and social hierarchies in general, come out of his belief in anarchism. For Chomsky, anarchism is not synonymous with chaos. It is a system of action and thought that seeks to dismantle power and privilege where it exists.

In life, Chomsky, now 86, is every bit the corduroy mandarin in elbow patches burrowed in teetering piles of books that I imagined him to be. Well, actually, when I met him on a frigid day in January, at his bizarrely trapezoid-shaped office at MIT, in a building designed by Frank Gehry, he was wearing a bright blue sweater, looking like le Carré’s famous mole-hunter George Smiley, but glinting with good humor and patience behind his owlish glasses. As any pilgrim visiting a wizened sage must, I wanted to ask Chomsky what he would do, if given carte blanche, to save our world—what he would do if he were president, say. But, with the utterly anti-authoritarian Chomsky, that somehow seemed inappropriate. I figured that, instead, we would talk about what could be done. Just days before we met, the attacks on French paper Charlie Hebdo and their aftermath had become a worldwide sensation. That seemed like a good place to start.

CHRIS WALLACE: I’ve been feeling increasingly queasy about the “Je Suis Charlie” consolidation of the event into a symbol of free expression, which is obviously part of what’s at issue, but not the whole issue.

NOAM CHOMSKY: It’s a very limited point. Actually, I thought the most interesting comment on it, inadvertently, was by Floyd Abrams. He’s a leading civil rights lawyer, a major exponent of the First Amendment. He had a letter in The New York Times in which he observed that this was the worst attack on freedom of the press in living memory, which is an interesting comment about living memory because it certainly isn’t the worst attack on the freedom of the press.

WALLACE: Not even within the last generation.

CHOMSKY: For example, take one case that was much worse, the U.S. bombing of Belgrade in 1999, which targeted and destroyed the main Serbian television station. The reason was because it was producing material that the U.S. objected to—namely, support for the government that we were attacking. Therefore, we bomb the station and put it off the air, killed over a dozen people. Is that an attack on freedom of press? But Abrams is correct—that’s not in living memory, because we did it.

WALLACE: It’s not admissible.

CHOMSKY: A couple years later, when the U.S. invaded Iraq, one of the worst crimes of the U.S. invasion—there were many—was the attack on Fallujah in November 2004. Take a look at The New York Times reporting it day by day; it’s very upbeat reporting, very supportive. The first day, the Times had a photograph on the front page of American troops occupying the general hospital in Fallujah, which is a major war crime in itself. But it was worse because the troops had taken the patients out of their beds, thrown them on the floor, manacled them, and thrown doctors on the floor, manacled them. This was shown in the picture then with very supportive commentary. But then there were some questions about why they attacked the general hospital, and military command said that it was a propaganda agency for the rebels. Uh, why? Because it was producing casualty figures, so therefore it made sense to occupy it and destroy it. Is that not an attack on freedom of the press? If a hospital is producing casualty figures that you don’t like? But that’s not in living memory. And there’s case after case that’s not in living memory.

WALLACE: What do you think are the biggest dangers, going forward, in the response to the Hebdo attacks?

CHOMSKY: It’s already happening: It’s an attack on radical Islam, “the biggest threat that’s faced by the modern world.” And radical Islam is very dangerous, undoubtedly—a couple of comments to make, however: where’s it come from? It comes primarily from our main ally, Saudi Arabia—the source of the extremist doctrines which are promulgated all over the Islamic world and also of much of the funding; a lot of the jihadi funding comes out of Saudi Arabia, our main ally. Furthermore, the United States has pretty consistently supported radical Islam against secular nationalism. The British did the same thing. Both imperial powers regarded radical Islam as not particularly problematic—it was secular nationalism that was the problem. And the jihadism, sectarian jihadism, is a direct outgrowth of the U.S. invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. I mean, it had existed in the past, but that really blew it up into a huge phenomenon. The current wave of radical Islamic attacks is coming from the people who fought in Iraq and Syria. Some of those who fought in Iraq, who we regard as terrorists, went to Iraq to support the resistance to the U.S. invasion. We call that terrorism. So if we invade a country, and people resist, they’re terrorists. In fact, under Obama, one of the first Guantánamo cases that came to trial—what they call a trial, a military trial—was a man named Omar Khadr, which is a very interesting case. He was picked up in Afghanistan by U.S. troops. He was a 15-year-old child then, and when U.S. troops attacked his village, he picked up a rifle and shot at them, so he’s a terrorist. He spent a couple of months in Bagram, which is a lot worse than Guantánamo, it doesn’t even have marginal supervision. Then they sent him over to Guantánamo for another few years—I think it was ten years altogether in these torture chambers—then, under Obama, he was finally offered a trial, a military trial. His lawyers were told he had two choices: he could plead innocent and stay there forever, or he could plead guilty and just get another eight years. So he pleaded guilty. He happened to be a Canadian citizen, so at that point the government of Canada agreed that they would take him and put him in a Canadian prison. This is a terrorist: a 15-year-old child who shoots back when soldiers invade his village. That’s terrorism.

WALLACE: What gets lost so quickly when the #JeSuisCharlie sort of simplification happens is the loss of sociological scope. We lose sense of who the attackers are, what their circumstances were, where they come from. And, pulling back a little bit, it’s interesting for me to walk around the campus here today. Because I live in this really densely populated neighborhood, in the East Village, and I know nothing of my neighbors. Whatever community once used to exist there—and it is sort of famous for being a strong community—is, well, gone. However, I think social media has provided something to activism in lieu of real, human, connected grassroots community. The responses to, say, Ferguson and Tamir Rice were nearly instantaneous. What do you think about this sort of switch in activist mobilization?

CHOMSKY: Well, I’m probably the wrong person to ask. I don’t participate. I have no Facebook page or Twitter—I don’t participate in it, and I don’t like it particularly. I mean, it’s a form of interaction [Wallace laughs], which strikes me as extremely superficial. We’re human beings; we’re not robots. And face-to-face contact is something totally different than typing a text message and then forgetting about it.

WALLACE: The existential element is virtually nonexistent. I have a thousand friends and am utterly isolated.

CHOMSKY: I see it with my grandchildren. They’re on social media all the time, and they think they have friends. But it’s not what I would’ve called a friend, ever.

WALLACE: There isn’t that same fulfillment, but do you think the Arab Spring and other movements have benefited in organizing and mobilizing …

CHOMSKY: It is an organizing tool. But take the Arab Spring: It was partially initiated by the April 6th movement, which is called the April 6th movement because a couple of years earlier the same group had offered their help to a major labor strike in the biggest industrial center in Egypt, which was crushed by the dictatorship, but they kept the name, and then they came back in April, in spring. That part’s been forgotten. Furthermore, at one point Mubarak closed the Internet to try to stop them. The organizing increased through face-to-face contact.

WALLACE: Do we have any sort of core organizing force anymore? The labor movement—that’s out.

CHOMSKY: Throughout American history, the labor movement has been under severe attack. U.S. labor history is much more violent than European, and by the 1920s, the labor movement had been virtually destroyed—reconstructed in the ’30s and ’40s, but immediately after the war, a major assault began against labor—by now it’s been diminished to practically nothing.

WALLACE: It feels as though what we have now is flash-mob activism, but we lack a consistent base.

CHOMSKY: There’s very little continuity. Take the Occupy movement. It’s typical in that it started from zero—no continuity with anything in the past, maybe some vague memories that there was once a civil rights movement, but the participants in it did not have a history of participation and membership and organizations which had continued throughout. Whatever you thought about the old Communist Party, it did provide continuity. The labor movement in countries where it’s survived provides continuity. The British labor movement is not a particularly radical movement, but when I go to England, it can be in a labor hall. You can’t give a talk in a labor hall in the United States. In the United States there is a kind of continuing core, but it’s through the churches, because those are the only institutions that have withstood the business assault on democracy: the churches have survived.

WALLACE: I’m so fascinated by the period in your childhood when you visited your uncle’s newsstand on 72nd in New York and listened to all of these engaged, socially aware workers and thinkers really wrestling with the problems of the day, positing political options for society, with the idea that the world could change, was changing all over the place at the time, and so why shouldn’t it for the better. There is something in the possibility of that activity, the belief in the potential for positive change, that I find impossibly alluring.

CHOMSKY: [laughs] Well, by then it was already all over. So you know New York. Well, Union Square used to be a kind of grungy, run-down place with a lot of small radical offices—the anarchist offices were there, and if you went down Fourth Avenue, it was pre-gentrification, so there were little stores, a lot of bookstores that are all gone, a lot of them run by émigrés, antifascist émigrés, some of them Spanish anarchists that hung around those bookstores picking up pamphlets, talking to people, going to the offices. This was all over the world. There was kind of a radical democratic thrust that developed out of the Depression and the antifascist war, but it was pretty much crushed. The conquerors—the British and the Americans—began to crush it as quickly as they could. My own childhood experiences, the things that I remember were, for example, when the British invaded Greece in 1944, and Churchill’s orders were “Treat Athens as a conquered city.” They had to crush the antifascist resistance, which was peasant- and worker-based and communist-led. That had to be crushed to restore the traditional pro-fascist system. The British couldn’t handle it, so they, by 1947, handed it over to the United States. That’s the Truman Doctrine—it was to crush the Greek resistance: antifascist resistance. The same thing happened in Italy. Starting in 1943, and when the British and American troops started moving up through southern Italy, the first thing they had to do was destroy the partisans. They had antifascist guerilla movements, which were very serious; they were holding down six Nazi divisions, and had liberated much of Italy before the U.S. forces moved in. They had to disperse the resistance, which was terrifying because they had established a socioeconomic system in which workers owned their own factories, and the idea that you wouldn’t have bosses, you wouldn’t have capitalists, was just horrifying to the British Labour Party, so it had to be destroyed. They essentially restored the old order, including fascist collaborators. I was, of course, watching all of it.

WALLACE: What was that like? I know that you’re sort of distrustful of heroes, so I gather it wasn’t as if you came up wanting to emulate some sort of mentor, or even excel within a specific institution or tradition, especially not to become a figurehead. But were there people who provided models for you, or modes of thought you were drawn to and inspired by?

CHOMSKY: Yeah. I was interested in anarchist cooperatives in Spain. You get a sense of it from Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, which I didn’t read at the time—actually, when it came out in the 1930s, it was suppressed. The reason was because it was anticommunist. You weren’t supposed to be anticommunist yet. It came out later on, as a Cold War document, which Orwell would’ve hated. But what impressed him—and he was not in favor of the anarchists; he didn’t like them but was impressed by them—he gives a very moving picture of the personal relationships, the elimination of authority, the fact that people talk to each other as equals. He said that there was something beautiful about what they were constructing and developing, and that’s the sense that I had as a child, too—though he didn’t like it.

WALLACE: And is that the seed of your own sense of anarchism, not as a system that one posits like a plan, but more like a process, a sort of undoing of power and privilege?

CHOMSKY: In fact, I didn’t know that much about the history at the time, but in Spain it didn’t just come out of nowhere. There had been 50 years of preparation, education, uprisings, crushing of uprisings, collectives. It was kind of in peoples’ heads when the moment came when you could do something, it kind of flourished. So it sounded and looked spontaneous, but wasn’t.

WALLACE: People were already living that way. It was a way of life more than a political apparatus. So was this just sort of infused into your upbringing?

CHOMSKY: It was personal; there was no upbringing. There were a couple of people who, you know, helped me think it through, but a lot of it was just personal.

WALLACE: Were you growing up very religious, in terms of belief and faith?

CHOMSKY: Well, my family was very Jewish and observant, but not religious. Like, they’d go to synagogue and celebrate the holidays, and I was a part of it as a child, but personally I wasn’t religious. I got turned off of religion pretty early on [laughs], partly because my father’s family was ultra-orthodox, and they hadn’t changed since Eastern Europe. In fact, he told me they’d even regressed beyond Eastern Europe, which was kind of medieval. But the hypocrisy was just shocking. I remember an incident, when I must’ve been about 10 or 11 years old when we visited his family for the holidays—they were in Baltimore, we were in Philadelphia—and I remember watching my grandfather smoking. He was ultra-orthodox, and I asked my father how he can be smoking, when I knew that there’s a rabbinic injunction—the holidays are just like the Sabbath except with regards to eating, so on the holidays you were allowed to cook dinner, but otherwise you can’t light a fire. I said, “How come he’s smoking?” And my father said, “Well, he decided that smoking is eating.” And I figured, he obviously thinks God is a total imbecile and he can cheat. If that’s what orthodox religion is, fine. Then I realized later that religion is really based on the principle that God is so stupid that he can’t see that you’re violating all of his laws by just finding trickery to get around them. Nobody can live up to the laws.

WALLACE: Is there something that you hold higher than yourself? A duty, say—something to which you’re devout?

CHOMSKY: I don’t think there’s any deep philosophy there; it’s just natural. People—their rights, their dignity, their individual capacities and options ought to be protected. I don’t think there has to be anything higher than that apart from your personal relationships, which, of course, are special.

WALLACE: Is there a story that you tell yourself, about yourself? Who are you, in your mind?

CHOMSKY: There’s nothing much to say. I’m an ordinary person, with ordinary concerns—these, of course, include those who are close to me and, to the extent that I can do anything useful, the vast problems of needless suffering, oppression, violence, terror, and even human survival. And in parallel, intellectual issues that have always seemed to me extremely challenging, discussed a bit in recent lectures [given by Chomsky at Columbia University in 2013 on language, human understanding, and the common good] called “What Kind of Creatures Are We?”

WALLACE: Do you believe man to be by nature good? In studying our fabulous displays of corruption and greed and fear and racism, how do you remain so patently optimistic?

CHOMSKY: I presume that each of us has the capacity to be a saint or a monster. The rest is up to us, although the circumstances of our lives impose complex conditions on such choices. As for being optimistic, it doesn’t seem to me much of an issue. We can decide that there’s no hope so we might as well give up and help assure that the worst will happen, or we can grasp what hopes there are, and they surely exist, and may be able to contribute to a better world.

WALLACE: I gather that there is disagreement whether the development of language, evolutionarily speaking, was as a way to speak to oneself, so as to better make sense of one’s own experience, or as a way to communicate to another. What is your feeling?

CHOMSKY: I think there is strong and mounting evidence to support the traditional view, that language is primarily an instrument of thought, secondarily used for a variety of instrumental purposes, among them communication.

WALLACE: Which makes me wonder, is there an evolutionary purpose for creativity?

CHOMSKY: Evolution doesn’t have purposes. People do. One purpose, I think, should be to allow for the fullest development of what I assume is a core part of human nature, the need to be free to think, to create, to develop and employ one’s capacities and interests and to do so in relations of mutual support with others, both enjoying their freedom and contributing to it.

CHRIS WALLACE IS INTERVIEW’S SENIOR EDITOR.