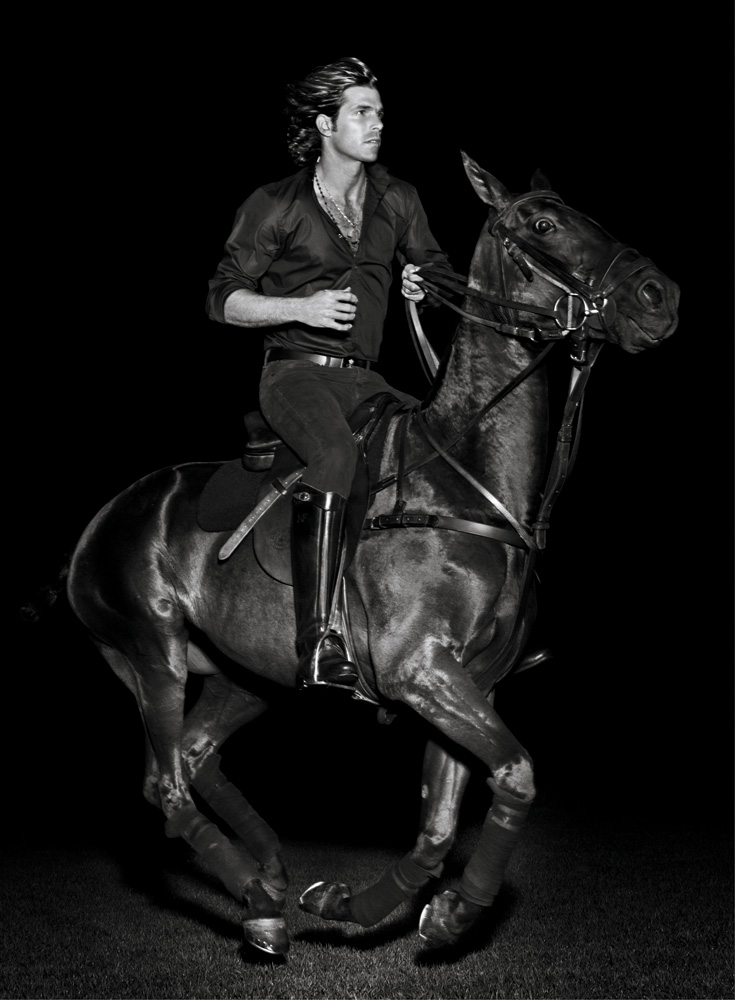

Nacho Figueras

Every sport has a star who—in and out of competition—comes to embody the character and personality of the sport itself. For polo, that athlete is Nacho Figueras. He is one of the leading polo players on the field today—maybe not the single best of the moment, but he does stand as the latest incarnation of the dashing Argentine player, an archetype that has a long history in the sport. And at age 32, Figueras has quite possibly done more than any other competitor to raise awareness of the sport. Polo hasn’t had an easy time in the last few decades erasing its public image as a rich man’s game, played behind the gates of private clubs to a crowd of white-gloved socialites. It’s a misconception that Figueras has spent much of his career trying to correct.

After all, Ignacio “Nacho” Figueras grew up on a small farm outside of Buenos Aires and began playing polo at the age of nine. He honed his skills in his home country before going pro and making a name for himself in Paris. He came to the United States more than a decade ago, working up to the top circuit that tours the polo capitals like Bridgehampton, New York, and Palm Beach, Florida. His current team, Black Watch, is one of the toughest and most skillful of the pack. But the rise in polo’s popularity the last few years also coincided with the rise of Figueras as more than just a champion. He has become something of the sport’s poster boy. In 2000, Ralph Lauren (with the help of photographer Bruce Weber) tapped him to model for the company. And, just this year, they made him the face of Polo fragrances.

Obviously, Figueras filling in the outline of the man on horseback that comprises Ralph Lauren’s iconic logo was as fitting as it was a brilliant marketing strategy. But Figueras sees his modeling job as another opportunity to call attention to the sport. Ironically, the public perception of Figueras is also somewhat misleading, fed by the notion of what a polo player must be like. He’s often perceived as a playboy, saddling up on the field in the day and partying up the night. In actuality, Figueras is a much more humble and centered family man—a husband and a father of two (at press time Figueras and his wife were expecting a third child). Not that there aren’t limelight moments. Take, for example, the Veuve Clicquot Manhattan Polo Classic, played last summer on Governors Island in New York City. In front of a crowd that included Madonna, Kate Hudson, Marc Jacobs, and Chloë Sevigny, Figueras and his Black Watch team sparred against a team led by Prince Harry. After the match, it was hard to determine if the attendees were more taken by the presence of the handsome prince or by the handsome polo player. The event benefited Sentebale, an organization that aids orphans and at-risk children in the African country of Lesotho, and it also benefited a number of guests who had never seen polo played live before—and certainly not on an island in New York Harbor. Interview’s chairman, Peter M. Brant, owner of the team White Birch and a polo player himself who has competed alongside Figueras, recently spoke with him at a café in Bridgehampton.

PETER M. BRANT: We’ve known each other for a long time, and one thing that has always impressed me about you is that even though you’ve been very successful outside of polo, doing things like modeling for Ralph Lauren, you’ve never lost your intensity for your sport. You are a polo player—and a lot of people don’t understand the level of dedication that it takes to be one, or even the game itself. So let’s start at the beginning. As a boy in Argentina, how did you wind up playing polo?

NACHO FIGUERAS: I grew up on a farm in Veinticinco de Mayo, near where Mariano [Aguerre, a fellow Argentine polo player] is from, and then I went to school in Buenos Aires until I was 12 or 13 because my parents wanted me to go to an English school. When I was 14, I decided that I really wanted to pursue polo more, so I asked my parents if it would be okay for me to go live on a farm outside the city so I could play. My mother said, “If you promise your school duties will remain normal, then I’m fine with that.” So I moved to a farm and lived with [professional polo player] Lucas Monteverde’s family. Being able to ride everyday allowed me to spend more time with the horses and to play polo more—that’s basically how this whole thing started. Then, when I was 17, I got my first opportunity to play as a pro in Paris, with Ignacio [Alvarez de Toledo] and Hélie de Pourtalès. I lived in a little apartment in the Château du Marais, and I was my own groom, so I would take care of the horses and then go play in the matches, too. It was a low-budget gig. [laughs]

BRANT: When did you start playing in the United States?

FIGUERAS: I played in Paris until ’97, when I came to play with [developer and polo patron] John Flournoy in Atlanta for a year. For me, this was interesting because it was how I started to learn about American culture. I always think of that year as a good introduction for me to America, because sometimes being in the Hamptons or New York City, you don’t really get the real extent of the American culture, but we were playing in Georgia and Tennessee . . . After doing that, I went back to Europe for two years and played in Spain. But in ’99, Nick [Manifold] and Mariano, who both were playing in Bridgehampton, called and said, “There is a place here if you would like to come and play.” So that’s how I started playing Bridgehampton polo. I played with Ashley Schiff’s team for two years, and then I started playing with you and the White Birch team, which I did for the next three.

I used the money that I was getting from modeling to buy better horses and to become a better player. There are many guys out there who look like me. But I think the difference is that I am a real polo player.Nacho Figueras

BRANT: Those years you played with White Birch were very winning years. We won a bunch of tournaments.

FIGUERAS: Yes, your team is still doing very well.

BRANT: After we played together, you started to play with Neil Hirsch and to develop his team, Black Watch.

FIGUERAS: Yes. We started the first season with Black Watch as a separate organization in Palm Beach in 2004. We played at 22 that year in Bridgehampton and then ’05 we started playing at 26. [Ed.: These numbers refer to the sum of the handicaps of all a team’s players. The higher the sum, the better the team.]

BRANT: So tell me now about your first introduction to modeling. How did that come about?

FIGUERAS: After my first year in the Hamptons in ’99, I got to know a lot of people. I went to some dinners at Kelly Klein’s place, and through her and through Ashley and through you and other people who are inside of this little polo world, I got to know Bruce Weber. Bruce shoots the Ralph Lauren campaigns. At the time, they were using Penélope Cruz for the women’s ads, and Bruce thought it would be good to use an Argentine polo player for the men’s ads, so they said, “Ah, the Spanish actress . . . and the Argentine polo player.” That’s how the whole thing started. I wound up doing my first shoot with Bruce for Ralph Lauren in November 2000, and then, right after that, I did a fragrance ad with him and Penélope. I continued to do jobs for Ralph for five years, and then I signed an exclusive contract with them. Now I am the face of all of the men’s fragrances and the Black Label clothing line. And then there is also the Black Watch collection that I am doing on the side.

BRANT: Now, polo is often perceived as a social sport, but in effect it’s a very macho sport. The guys who play polo, as a group of characters—if you were looking to cast the essence of machismo as a person, then you might as well go to a polo match and pick any of those guys.

FIGUERAS: Yes. You could go to a polo match and take your pick without making a mistake. [laughs]

BRANT: So in that world, the whole idea of modeling . . .

FIGUERAS: Is sort of contrary.

BRANT: To the culture, yes. Today, I think there’s a different attitude towards it because you’ve managed to do it successfully while still remaining true to your roots in the sport. But when you first started, even I, as someone who played with you, could feel a certain reaction amongst the other players. The feeling was, “Well, Nacho’s a model now. He won’t spend any time on polo.” But you actually put your resources back into the game.

FIGUERAS: It’s true. In the beginning, I was getting all this feedback from people saying, “What are you doing? What is this?” But I thought to myself, “This is a great opportunity. This is a perfect bridge to help me achieve my dream and my vision of polo becoming a bigger, more visible sport.” So I used the money that I was getting from modeling to buy better horses and to become a better player. There are many guys out there who look like me—you know, brunettes with long hair. There are thousands. But I think the difference is that I am a real polo player, who does endorsements for Ralph Lauren on the side, and I’ve always looked at it that way. So I really believed that if I could elevate my game and show that I was serious about it, then the work I was doing with Ralph Lauren would become that bridge that I was looking for to take the sport further.

BRANT: I think you’ve done a superb job in that regard. As a player myself, I’ve always thought that it was important for both the sport and for the United States Polo Association to embrace what Ralph Lauren was doing, and to try to build a closer relationship with the company. The image of the polo player and that of Ralph Lauren as a brand are obviously very synonymous. But the relationship between the association and the company has at times been adversarial because there were always branding issues. As you well know, the Polo Association has sometimes shot itself in the foot when it comes to promoting the sport.

FIGUERAS: I’ve always felt that it was a destructive situation. Yes, the Polo Association now has its own franchise and does its own clothing. But how can the uspa promote the sport by fighting with a brand like Ralph Lauren? To me, the best thing to do would have been to just to sit down and say, “Okay, whatever happened, happened. Let’s start from scratch. If we can work this out, then it’s a win-win situation for everyone.”

BRANT: Many times in the past, people have tried to do that—myself included—but none of those efforts ever really got anywhere. That’s why I think the kinds of things that you are doing—both as a polo player and in your work with Ralph Lauren—are so important. They involve interacting with people outside the polo world, which is crucial because a lot of people don’t really know what our sport is about. The common conception of what goes on at a polo match still seems to be that it’s something like that scene in Pretty Woman [1990] with the tea and crumpets on the lawn. The sport is still really perceived in that light.

FIGUERAS: I think the problem is that polo is still seen as a very elitist sport—and, yes, it has been around for thousands of years and has all this tradition. I think the concept of polo that people had in the 1920s and the 1930s was much more accurate, when going to a polo match was seen as a great day out and great fun on a more popular level. But after World War II, that idea about polo somehow got lost. Now, people tend to think that polo is only played in places like the Hamptons and in Palm Beach. They wonder, “How can I get there? Am I going to be in invited? What am I going to wear?” And, to me, polo is so not about that. Polo is a great thing to do with your kids and your family—it is a great day out. And to me, horses are amazing creatures that give you this cable to Earth and put you in contact with nature. I see polo as a sport that connects a groom from Argentina to the Queen of England—and the total opposite of elitist. With the Manhattan Polo Classic that we put together, the idea was to show that side of the sport to the people of New York, where polo was once very popular, by bringing the match closer to the city and getting rid of all those barriers. We first tried to hold the exhibition in Central Park, but that didn’t work, so Governors Island, which is a five-minute ferry ride from Manhattan, became a good fit. I was really impressed with those 4,000–5,000 people who came to see the match. They were just screaming and yelling and having a good time.

BRANT: Yes, absolutely. The crowd was very into the game. Prince Harry played in the match and had a great time. My son, Christopher, played in it too, and enjoyed himself. I thought that Mark Cornell [the ceo of Moët Hennessy USA, which co-sponsored the event] did a great job in working with us to make that day happen.

FIGUERAS: He did an amazing job. He saw what we were trying to do, and understood it, and gave us what we needed to do it right. I really believe that the most important thing is to bring the sport closer to people. The environment, the entertainment, the characters—you need all that to connect with them. This year, we played the 105th U.S. Open, and for the last 40 or 50 years, polo hasn’t really changed that much, so we really need to push the sport from another angle. If we don’t shake it up and promote it, then it’s never going to have a higher profile. We need to show people that polo is a sport that has a lot of potential and that they can even play. We need for kids one day to look at polo players and grow up saying, “I want to be that guy.”

BRANT: Right. If you have access to the sport, then you can have that dream. We assume that people know the star players, like Adolfo Cambiaso or Gonzalo and Facundo Pieres—to you and I, these are a few of the greatest polo players who ever lived, but the general public doesn’t know that. There are many stars, many stories, and many interesting aspects of polo, but generating a greater awareness of the sport has to happen on a grassroots level. But I believe that polo has a great future as well. I don’t care if I’m playing in a cornfield somewhere or there are 5,000 people there—it doesn’t make any difference to me. I just love to play.

FIGUERAS: Because you have passion for the game. You know, I come from a middle-class family. My father worked hard for me to be able to have a horse, for me to be able to ride. And so I really believe that if there is a kid who, for example, is growing up in a place like Texas, whose father owns a ranch—or even works on a ranch—and this kid has access to a horse that he can ride every day, then that is a potential polo player. Obviously, if you’re growing up somewhere like New York, then it’s harder, but you can still look at White Birch estate and say, “Listen, I love horses. I would like to get a job as a groom.” That kind of thing happens in golf. Ángel Cabrera, who won the masters earlier this year—he was born in a town in Argentina that had a pretty big golf club, and he started out caddying there. But everything all begins with people having an understanding of the sport.

BRANT: I don’t think a lot of people know this about you, but you are a real family guy. Your wife, Delfina, and your kids are lovely. I don’t know of any wife who cheers more for her husband than Delfina does for you. I can always hear her on the sidelines. [both laugh]How much time do you now spend in the United States versus Argentina?

FIGUERAS: I spend about six or seven months of the year in the United States, mostly between the Hamptons and Palm Beach. And then, last year, I went to England for a while, and then there were some trips here and there for Ralph to Europe and Russia. So about eight months out of the year I am on the road, but my wife and kids are with me most of the time. BRANT: On the fashion side, who do you feel like acted as a guiding light for you in terms of showing you the ropes and helping you along?

FIGUERAS: Well, Bruce Weber has always been very important in that side of my life. It’s been about 10 years since I started shooting with him for Ralph Lauren. Obviously, I have worked with him many, many times now, and I feel very lucky to be able to say that I am working five, six, seven times a year with a legend. He has always told me that the most important thing is for me to be true to myself—to be myself—no matter what I’m doing. So I have been fortunate that he has always been very supportive of me.

BRANT: Bruce has a long history with Interview. He’s shot some of the greatest issues—the 1984 Olympics issue, for instance, comes to mind. I always remember many years ago asking my very good friend and mentor, the great art dealer Leo Castelli, when so many young artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat were developing in New York, “Who do you really like who is up-and-coming?” And he said, “A photographer—Bruce Weber.” Leo saw something in Bruce’s early photographs that we all see in his photographs today: That he is a true artist.

FIGUERAS: Yes. You see a Bruce Weber picture and you know it’s a Bruce Weber picture—it’s amazing. And then Ralph Lauren, of course, is someone who has also been very important. Ralph once told me something that has always stuck in my head. He said, “You know, I never did this for the money. I had a dream and I pursued that dream, and then everything happened, but I never did this for the money.” And I accept that from him, when you look at how he has led his life and run his company for the last 42 years. But I also really believe in that philosophy myself.

BRANT: One of the memories I will always have is of a time I visited Ralph in Montauk [New York]. He took me to a storage area where he had some of his cars, and he let me drive a red California Spyder. I’ll never forget it. It was probably a 1963 or 1964 California Spyder. He was sitting in the passenger seat, and we drove through the hills of Montauk. I’ve always appreciated that he let me drive that car. It’s one of the most beautiful cars ever designed—you know, the Pininfarina design. So it’s nice to hear you’ve had great mentors like Bruce and Ralph in your life.

FIGUERAS: Yes. I feel like they’ve been very good role models for me.

BRANT: So beyond modeling, have you been interested in maybe doing some film work or other stuff outside of that?

FIGUERAS: Obviously, TV is the one thing that we are missing to really take polo to the next level. So I’ve done a couple of TV shows, like Late Night With Jimmy Fallon and the Today show. I also did an episode of Gossip Girl where I play myself. I play Nacho, the polo player, and I wear my Black Watch shirt. What I am trying to do is reinforce theBlack Watch name and the Black Watch brand. Black Watch to me is another instrument to really get polo out there. We need our version of the Yankees or the Chicago Bulls. We need those things so that we have a base of fans that can follow those teams around. Because so many players in polo play for so many different teams, it can be very confusing. So, obviously, TV is a factor. So when they said, “Nacho, we would like to have you in the Gossip Girl show, you know, being yourself,” I said, “Amazing, that’s great. But I will only do it if I’m Nacho the polo player and I can wear my Black Watch shirt.” And they agreed to let me do that. I’ve had some opportunities to do some films, but I’m just waiting for the right project to come around. For example, the Tom Cruise movie Days of Thunder [1990] did so much for NASCARracing. So what we need is our own polo movie.

Peter M. Brant is the chairman of Interview, Inc.