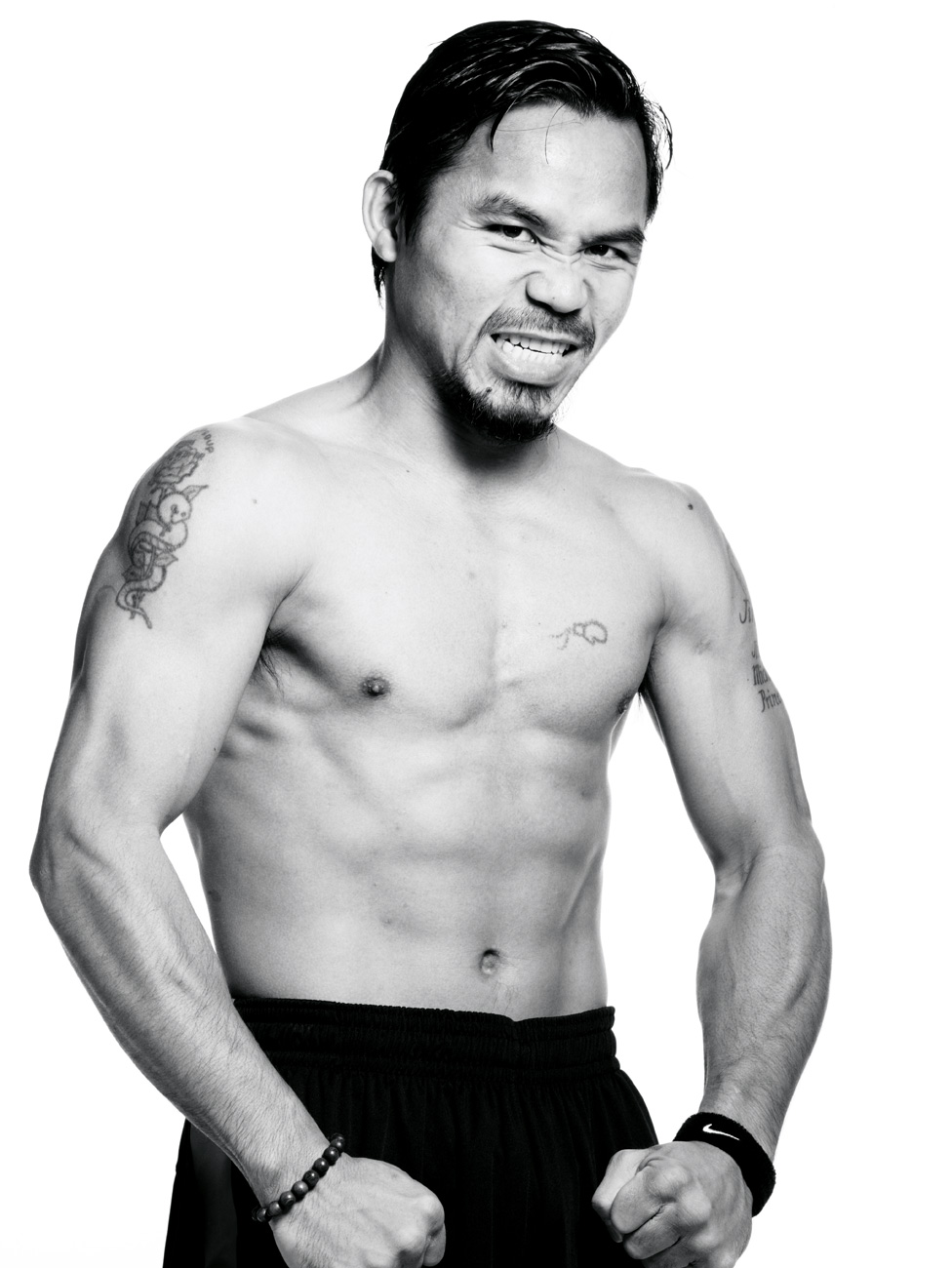

Manny Pacquiao

For a guy who dismantles his opponents in the boxing ring with lethal speed, Manny Pacquiao speaks very softly and slowly. But don’t let that gentle voice fool you: Pacquiao is one of the most talked-about, decorated, and feared fighters in the world today. He is the only boxer in history to have won world titles in seven weight classes—a fact that has conferred upon him near-deity status in his native Philippines. Following his victory by unanimous decision over Joshua Clottey in March, he has posted a not unsubstantial 51 wins (against three losses and two draws) since he began fighting professionally in 1995. And while Pacquiao’s on-again, off-again rumored next opponent and chief rival for the title of “Best Fighter on the Planet Right Now,” Floyd Mayweather Jr. (click here to read Interview‘s feature on Mayweather Jr.), remains undefeated at 41–0, most boxing watchers acknowledge that Mayweather’s record can only gain the sort of historic recognition he craves if he finally confronts and defeats Pacquiao.

To observe Pacquiao in the ring is to watch a highly trained fighting machine gone slightly berserk. Muscular, compact, and diminutive, the 31-year-old Pacquiao throws punches in bunches of six and seven with a manic, unflagging intensity, and a velocity that leaves even seasoned opponents stunned. A southpaw, he attacks from every angle with extraordinary energy—and often looks surprisingly refreshed after his matches, like he’s just completed a workout. Indeed, last fall, Pacquiao scheduled a musical performance at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Vegas on the evening of his much-anticipated match against Miguel Cotto—which Pacquiao won decisively by technical knockout. Oh, yeah—Pacquiao is also a singer.

In May, Pacman, as Pacquiao is known, added yet another landslide victory to his résumé—this time, a political one—when he was elected congressman to the Sarangani province in the Philippines. (For followers of Philippine politics, he defeated RoyChiongbian of the ruling Chiongbian family, which had been in power for more than two decades, by a nearly 2-to-1 margin.) Pacquiao is also a sergeant major in the Philippine army reserve, and he recently completed his first starring role in a feature film, Wapakman, which was released in his home country late last year, and is rumored to be in talks with Sylvester Stallone about developing a movie starring both of them.

Following Pacquiao’s defeat of Clottey and Mayweather’s hard-fought victory over ShaneMosley in early May, a meeting between the two champions seems, at press time, to have inched closer to becoming a reality. We spoke withPacquiao, while he was at home in the Philippines.

Photo: Manny Pacquiao in Los Angeles, July 2009. All Clothing: Nike Sportswear. Hair: Yannick d’Is for Cutler/Redken/Management artists.

Floyd [mayweather] is also a good fighter. He has different style than the fighters I’ve fought. He’ll run and run and run and then run again. . . . but I know that I’m faster and stronger.”Manny Pacquiao

DIMITRI EHRLICH: You’re the pride of the Philippines. They even put you on a postage stamp. What happens when you walk down the streets in the Philippines today?

MANNY PACQUIAO: I can’t walk down the streets. It’s very difficult. I can’t go to the mall. I have to go to hotels just to have a meal. Everybody wants to say hi and say thank you and congratulate me, so it’s very difficult.

EHRLICH: Your hand speed is legendary. How do you account for it?

PACQUIAO: Most of it—all of it—is god-given, but in our training that Coach Freddie—Master Freddie [Roach]—and I do, we like to focus on my advantages and my strengths and better them, so that those advantages are even greater against my opponent. Rather than trying to play to his game or to better my power, I’m much more focused on my speed, so that the disparity is even greater against whomever I fight.

EHRLICH: It’s been said that boxing is the art of hitting the other guy without letting him hit you. But you don’t seem afraid to take a punch.

PACQUIAO: Getting hit is part of what we signed up for. It’s something that I know is going to happen when I get in the ring. I actually look forward to it, because it’s something that I know people love. People like that kind of style. It’s important for me to win the fight, but it’s not the most important thing. The most important thing is to show people who spend their hard-earned money that they can be entertained by the way I fight.

EHRLICH: Now, you’ve managed to hold titles in seven weight classes so far, something that nobody else in the history of the sport has ever done. Does there come a point at which you just feel like you cannot possibly face an opponent who’s naturally that much heavier than you?

PACQUIAO: My first fight was at 108 pounds, but I was only 96 pounds. I was 16 years old. The last fight, I fought at 145. I’m growing still; my body is getting bigger. I walk around at maybe 150 to 155 naturally. I think this will be my maximum, because the guys are bigger and heavier at 154 pounds.

EHRLICH: Yeah, how tall are you?

PACQUIAO: I’m five foot six and a half, five seven.

EHRLICH: What are you thinking about when you’re in the ring?

PACQUIAO: I think you can see in the Cotto fight. The first four or five rounds, I was letting him hit me. I was just standing there, taking his punches. That was part of my mental conditioning—to show him that no matter what he does, no matter what kind of punches he throws, I’m not going to get hurt and I’m not going anywhere. I’m just going to come forward and try to beat him. I think that it showed, by the sixth round, that he couldn’t hurt me.

EHRLICH: Everyone’s anticipating the possible bout between you and Floyd Mayweather Jr. What are the challenges in your facing him that are specific to him?

PACQUIAO: Floyd is also a good fighter. He has different style than the fighters I’ve fought. He’ll run and run and run and then run again. So it’s just a matter of me chasing. . . . Master Freddie will have to come up with a good game plan so that we can cut off the ring and get him to trade punches with me. But I know that I’m faster and stronger.

EHRLICH: I understand why you got the nickname Pacman from your last name, but you’ve also been called the Mexicutioner because you’ve fought a lot of Mexican fighters. Is there an element of ethnic rivalry between Mexican and Filipino fighters?

PACQUIAO: No. I fought 8 or 10 fights in a row where I fought Mexican-Americans or Mexicans, and I’m able to see that Mexicans appreciate my style because a lot of them are rooting for me. I have lots of Mexican fans, and some of my sparring partners and even guys I’ve fought who are Mexican have said to me that I fight like a Mexican. So it’s an honor to have fans and to have the respect in other countries. No, I’m not a Mexicutioner. I’m only Pacman.

EHRLICH: Fighting Mexican-style means basically to stand there and weave without dancing away, right?

PACQUIAO: I think it’s just the heart. They’ve shown that they don’t back down. They don’t quit. They don’t care. They stand in there and trade punches.

EHRLICH: I was watching some of your sparring tapes, and it looks like you go pretty hard. You knocked one of your sparring partners to the mat with a body shot.

PACQUIAO: Normally we have four different people trying different things. We have guys for speed; we have guys for power; we have the brawlers, the guys that like to foul. . . . We have to be ready for anything in the ring.

EHRLICH: So you specifically get in the ring with people who are throwing elbows and hitting below the belt?

PACQUIAO: Yes, yes, depending on the opponent. We have to know what kind of tactic to do against something like that—just in case that happens.

EHRLICH: Speaking of shady businesses, you’re also in the music industry. You’re a multiplatinum recording artist in the Philippines. How did you get into singing?

PACQUIAO: I don’t know the number but, yes, people buy my album here in the Philippines. My concert was a success in America. After the fight [with Cotto], a lot of people came.

EHRLICH: I was kind of amazed that you scheduled a performance immediately after a 12-round fight. Did you ever think, Maybe I won’t really be up for singing onstage? What if you’d been badly beaten?

PACQUIAO: You can’t think of it that way. You have to always think positive. I had fun. It’s very relaxing for me to sing. It’s a good break from the hard training and the fighting. I’ve come out with two CDs. We’re going to come out with an English album, too. I sing mostly ballads and a little bit of rock. That’s what’s popular here in the Philippines.

EHRLICH: What would you say has been the toughest fight you’ve had so far, and why?

PACQUIAO: The toughest would probably be with Miguel Cotto. He’s a very tough fighter. It took me a while to get used to the style. The fights with [Juan Manuel] Márquez and [Erik] Morales were also difficult. The best fight—the best performance—I think I’ve had was against [Oscar] De La Hoya. I think that was my best night, followed by [my fight with Ricky] Hatton, and then Cotto.

EHRLICH: It’s interesting that you say Cotto was your toughest fight even though you didn’t lose it. You have lost one or two before. But the toughest one you actually won.

PACQUIAO: He’s a tough guy. He just keeps coming. He wouldn’t go down.

EHRLICH: Have you ever been involved, as an adult, in a fight outside the ring?

PACQUIAO: Not in the last 15 years.

EHRLICH: Tell me about your political career.

PACQUIAO: I’ve learned a lot from politics. It’s a very dirty business here in the Philippines. That’s the reason I’m in it now, to change the view of it and the overall way of politics here in the Philippines. I’m coming in as somebody who already has money, who doesn’t need money number one, doesn’t need to be corrupt, doesn’t need to take advantage of people. But also somebody who has been there—to help the people who are suffering, and that is where I was. To show them that it can be done.

EHRLICH: What was your childhood like?

PACQUIAO: We were very, very, very, very poor. Sometimes we had one piece of fish for the entire day. Sometimes we just had rice. We mixed it with water so that we could have a little bit of a soup. We call it ngaw here in the Philippines; it’s just rice broth. It was very difficult. That’s why I had to work when I was very young, to help support my family, to help my brothers and my sister go to school. It was a very difficult time. That’s how I grew up.

EHRLICH: What jobs did you do?

PACQUIAO: I’ve worked in construction, in a factory sewing clothes. I also sold flowers and doughnuts—just odd jobs to try to make 10 pesos, which is equivalent to 20 cents.

EHRLICH: Forbes said that you earned $40 million last year. How much have you earned in your career so far as a professional boxer?

PACQUIAO: I don’t know how much exactly I’ve earned. I think the IRS knows how much I’ve earned.

EHRLICH: Despite your popularity, you had to bring a lawsuit against a newspaper in the Philippines that wrote an article claiming that you were a compulsive gambler. Do you actually gamble?

PACQUIAO: I used to play a little bit, for fun. It’s okay to play poker, but not to the point where it’s hurting me, my family, or my income.

EHRLICH: The house you grew up in—did it have running water?

PACQUIAO: We were in a one-bedroom hut made of bamboo and cardboard.

EHRLICH: A dirt floor?

PACQUIAO: Yes.

EHRLICH: Was there running water?

PACQUIAO: No, no, no.

EHRLICH: So you’ve gone from living in a dirt-floored hut with no running water to being one of the richest people in the Philippines. Do you ever wake up sometimes and think, Is this really happening?

PACQUIAO: Yes, sometimes. I also question, “God, why me? Am I special in any way?” I’m just appreciative of everything that has happened in my life—I’m overwhelmed, sometimes, by this. When I see where I grew up and the places I’ve been, it puts a smile on my face because of all the people there I can help. I give them food; I give them money; I try to provide them with a good lifestyle, and do the best I can because that’s where I came from. Those are my people.

EHRLICH: When you were young, did you know it was going to happen?

PACQUIAO: I always knew I would be world champion.

EHRLICH: Now, you’re also a sergeant major in the Philippine army reserve. When was the last time you actually put the uniform on?

PACQUIAO: Maybe a year ago. We had a special award for one of our generals, and I came to visit and gave him his award. But I’m ready to fight for my country. I’ve always fought for my country, in my own way, showing that Filipinos are a strong people and can do anything that they put their minds to. But if the army needs me, I’m ready. Always ready.

Dimitri Ehrlich is a contributing music editor at Interview.