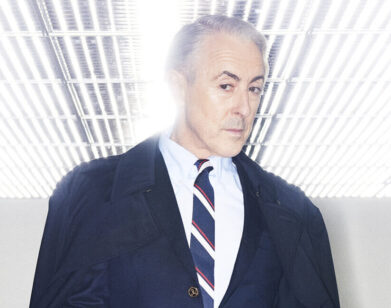

For John Boyne, Love is a Battlefield

John Boyne’s novel The Absolutist (Other Press) tells the haunting story of a young soldier’s doomed romance with a fellow soldier. The protagonist, Tristan Sadler, is a young gay man disowned by his family. He finds company and camaraderie when he enlists in World War I. What he is not prepared for is falling in love with Will Bancroft, a charismatic boy he will soon fight alongside. Will is by no means ready to acknowledge his own complicated passions. Amidst the bloody trenches of the battlefield, the two men wage their own personal struggle, leading to heartbreak and tragedy. Boyne gets into Tristan’s head brilliantly, constructing a compelling first-person narrative that takes us from the horrific front to the devastated countryside after the war, where Tristan connects with Will’s older sister. The sole survivor from his troop, Tristan attempts to find understanding for himself, his deeds and his doomed love.

Poetic, passionate, and poignant, The Absolutist is about self-discovery, friendship, and how far bravery can take us. Interview spoke with Boyne about beauty in the midst of violence, why we no longer view war as honorable, quests for forgiveness, and how forbidden love can both tear people apart and bring them irrevocably together.

ROYAL YOUNG: I want to talk about people who like to be surrounded by beautiful things and where that comes from.

JOHN BOYNE: I wanted to establish Tristan early on as a man outside of his times. He wouldn’t be quite like the other soldiers; he has a more aesthetic soul.

YOUNG: What happens when someone like that is surrounded by the crudeness, camaraderie, and violence of war?

BOYNE: One of two things could happen. One is that you completely fall apart and can’t deal with the situation around you. Tristan surprisingly does adjust to what’s going on around him, perhaps because he doesn’t have a good family life. He is very isolated. But in the army, he experiences the opposite, he is part of something. The camaraderie is more important to him.

YOUNG: In between the war and the narrative that takes place after, Tristan seems so much older. He’s only 21, but there’s this old-man-like quality he takes on.

BOYNE: I knew his tone after the war would have to be of someone who was old despite his youth. Early on, there’s a scene between Tristan and young boy who was just a year or two too young to go to war. But the difference between their attitudes to life and to war is so marked.

YOUNG: Tristan’s weariness seeps through.

BOYNE: And the shame and remorse.

YOUNG: Reading about World War I, there’s a sense of honor and gaiety about war we don’t have anymore. Now we protest wars; as a culture we’ve changed so much.

BOYNE: War today is such a more visible thing. We see it on television, on CNN. In 1914, war was a concept. There was a naivety and stupidity that war would be a great lark. It’s not that different from Gone With The Wind, where all the young men can’t wait to go off to fight and then two hours later in the movie, we see how the reality of that has come home to them.

YOUNG: It’s so hard to imagine a time when people were so blind to that destruction and devastation.

BOYNE: Today people can see and protest all the different interests that want war to happen, the people it financially benefits. The First World War wasn’t fought for that reason. The Second World War wasn’t fought for that reason. Your entire country and way of life could be overtaken. The First and Second World War, had they ended differently, would have ended with a completely different Europe.

YOUNG: Why do we go on quests for understanding or forgiveness?

BOYNE: In Tristan’s case, he feels tremendous guilt. But he doesn’t want anyone to explain it to him or tell him he should be forgiven. He wants to suffer. He wants to feel pain. Unless you’re very boring, I think most people who’ve lived long enough have something in their past which will never go away. As a writer, my interest has become in writing about much more emotional, personal topics. I’m trying to reach into subjects I have never written about before.

YOUNG: What are those subjects?

BOYNE: I’ve never written about being gay before. I don’t buy into the idea that an Irish writer should write about Ireland, or a gay writer should write about being gay. But when I found the right story, I saw it as an opportunity to write about being a teenager and being gay. Most people, whether you’re gay or straight or whatever, have experienced that relationship where one person is much more interested than the other. I wanted to write about that and I found it in Tristan and Will. Will is not in the same place as Tristan. Tristan is too emotional.

YOUNG: It’s about love, loving out of place and turn. What happens when you love someone and you can’t show it?

BOYNE: Well, for Tristan and Will, what they’re doing is illegal. But also, Will doesn’t have the language for it. Tristan has been thinking about it since he was 14 years old. It’s a subject he’s already explored in his mind, tried to come to terms with and understand. Will is arriving at Aldershot Barracks having never thought about this before. When he is talking to Tristan about the girls he’s known back home, he doesn’t realize what he’s saying, that his disinterest in them is for a reason. What frustrates Tristan is that Will can’t put into language what it is he’s feeling. Maybe if their relationship was taking place not in the trenches of the war, it would be different. For Tristan what is going on is love, but for Will, what is going on is morality. For Will, what’s going on around him all day, every day is much bigger than what for him is a physical release.

YOUNG: It seems that there is some fear for Will, that Tristan represents something that scares him. The physicality of their relationship seemed like an escape and release from what’s going on around them.

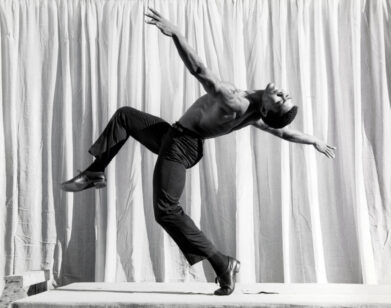

BOYNE: That’s certainly true. When I was writing the novel, I thought of all the young men in the trenches at that time. There would have been gay young men, though they may not have known or been able to express it. But relationships must have formed and the relief that you might get in intimate moments from the horror around you must have been an extraordinary thing.

THE ABSOLUTIST IS OUT NOW.