How Cheryl Strayed Found Her Path

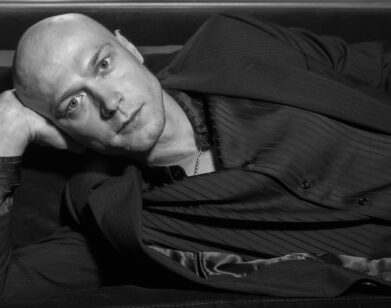

PHOTO COURTESY OF JONI KABANA

Cheryl Strayed was 22 when she first brought her mother through the doors of the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In weeks, she watched her mother pale, wither, and pass away. After years of grasping to come to terms with her mother’s death, she found a book on hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. She quickly decided to attempt it. The thing was, she had never backpacked before and was set on going out alone—a beautiful blonde woman determined to hike ice, rock, and snow for over a thousand miles. Her new memoir, Wild, is a tale of facing those things that may just break us, written by a woman who’s had her own kind of breakout recently—she was revealed last month to be the author of Dear Sugar, literary website The Rumpus’s much-beloved advice column.

We sat down with Strayed in Chicago, almost one year after our first meeting, to talk about the soundtrack in the mind, finding your most savage self, and scars that we eventually shed.

JENNIFER SKY: Wild, your first memoir, is about your 1,100-mile hike along the Pacific Crest Trail. You took this walk to recover from the loss of your mother, who had lung cancer and passed away within three months.

CHERYL STRAYED: Seven weeks to the day after her diagnosis with cancer.

SKY: She was 45?

STRAYED: She was 45. We were both seniors in college at the time. My mom was just about to graduate from college, and she died on the Monday of our spring break. Her funeral was on Friday, and then I went back to school that next Monday. I went forward with my life not because I was strong, but because I had to. Whenever people say to someone who is experiencing a big loss, “Oh, I don’t know how you can do that, I couldn’t go on…” in an effort to be consoling, I always bristle. I appreciate that they are trying to be kind, but nobody has a choice about going on. I had to go on without my mother, even though I was suffering terribly, grieving her. My whole life sort of ended when my mom died. I had to remake it again and be a new person in the world without my mom. It was a very primal rebirth, that time after my mom died.

SKY: I think one of the most courageous passages is at the site of your mother’s tombstone. You spread out her ashes and there were a few pieces of larger bone left and you actually placed them in your mouth and swallowed, echoing her words that are the epitaph on her stone, I’m with you always. Did you know you were going to do that?

STRAYED: No, I didn’t. We were spreading the ashes and I just couldn’t let go of them all. I couldn’t bear losing every material aspect of my mom. I had to keep a physical part of her with me. So I put those strange ash bones in my mouth and swallowed them. I remember even at the time that it was sort of crazy. My mother’s death put me in touch with my most savage self. As I’ve grown up and come to terms with her death and accepted it, the pieces of her that I keep don’t exist materially. They are things like how I love my kids.

SKY: Being a caregiver for somebody that is sick, you feel the lasting weight of illness and death. Obviously you still carry this. There was a moment on the trail that really stuck with me, I don’t know why—there was a fox that you just called out to. You were like, “fox, fox,” and…

STRAYED: I was naming the animals.

SKY: And it started to walk away and you said “Mom.” It just suddenly occurred to you. What was that, any idea? Has it happened again?

STRAYED: You know, it has. It’s funny to talk about because it sounds completely crazy, but I have absolutely met animals who’ve seemed familiar. In them, I’ve recognized the essence of the spirits of certain people I’ve loved, almost always my mother. I don’t think I’m the only one who does this. When someone you love truly dies, you have to find them over and over again in the world, and I think you do that on a very psychic, unconscious level, and I think in some ways I was calling out to that spirit of my mother when I saw the fox. It doesn’t surprise me it’s in animals that I find my mother. She was the great animal savior of northern Minnesota. When she died, all the veterinarians in the area sent huge bouquets of flowers to her service, because they knew that. My mother saved hundreds of animals in her life. Wherever she encountered and injured or needy or abandoned animal, she brought it home. I have seen dozens of animals die because she often would find them on the road almost dead. Dozens more lived because she saved them.

SKY: There are so many people on this walk that you talk about and there are so many people that care for you on this walk. There are actually three guys that you come across that deem you the “Queen of the Pacific Crest Trail” because you do have kind of have a gifted walk in a way. Do you think you could have made it without all these wonderful people you came across?

STRAYED: Probably not. There’s a wonderfully generous and warm culture on the trail. Generally when I met another hiker, I instantly felt like we were kindred spirits. There’s a connection that cuts across age, class, gender. You really just feel like you’re in that together. I think being a woman alone enhanced the impulse in others to be generous. What we’re told is that to be a woman alone is to be in a dangerous situation. The message is that people are gong to prey on you and do bad things to you. That may be true in some cases, but what I experienced was the other case. Nobody is threatened by a woman alone. Instead, they want to help you. I think a lot of people who saw me were excited about what I was doing and so they extended themselves.

SKY: There’s a lot of music in Wild, even though you were out in the wilderness, unplugged.

STRAYED: That was one of the most surprising parts of that hike, because I love music and listen to music all the time, but I didn’t realize how much my body needed music. I needed it more than sex. I write in Wild that I didn’t even masturbate on the trail because I was so exhausted at the end of each day and grossed out by myself. But music. I could not go without that. My mind would not let me be without music. I hiked the trail in 1995—before there were iPods or music on our cell phones or even cell phones. So I was truly out there with just my thoughts. After a few days there was a continuous loop of songs playing silently in my mind. In Wild, I call it the mixtape radio station in my head, because the things that would play on it would be like the Burger King theme song—things I didn’t even want to hear—along with songs I love by Lucinda Williams, Wilco, Joni Mitchell, and others. You could go through the book make a mix tape, a Wild soundtrack.

Being so alone and so silent for so long gave me the opportunity to see how our brains actually work. I think of that so often in my regular life, as I’m always interacting with people or with my computer or phone. My brain is being directed constantly in my life now, but on my hike it was left to wander. That was often maddening because it was tedious and monotonous sometimes, but then my the mind would take over, and that’s when I’d start hearing the music in my head, or I’d find myself reliving the second grade and thinking through that whole school year, or thinking deeply about people I know or things that I didn’t even know I remembered anymore. Those thoughts would be there. I wouldn’t have had them otherwise.

SKY: You talk about injuries you incurred on the trail. Do you have any marks left? Are they permanent scars?

STRAYED: Oh, like the calluses on my hips? No. All my toenails grew back, but it took several years. It was a really long slow process of the toenails growing back. I can tell there’s some ridges, I know that that’s from my big toenails having lost them, and my hips, the skin, it took several months, they sort of shed the skin. That’s the beauty of the body, it regenerates, so no—no permanent scars. I can still tell on my finger, too, when the bull charged and my skin was scraped off to the bone, but it’s very discreet.

SKY: Would you do it again if you could, like at this moment?

STRAYED: Absolutely. In a heartbeat. Aside from marrying my husband and having my children, hiking the PCT was the best thing I ever did. The hike very literally forced me to put one foot in front of the other at a time when emotionally I didn’t think I could do that. You have to keep walking, no matter what. If you don’t, it’s a living death. You’re just standing in one place dying. So I love that the hike gave me that metaphor, a map of how to survive life, to keep moving, to go far.

WILD IS OUT TOMORROW.