Farah Pahlavi

they cannot stop culture. And sometimes when there is pressure, artists become more creative. Farah Pahlavi

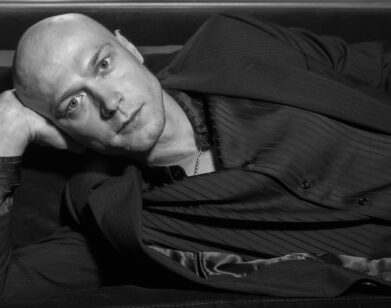

Her Imperial Majesty Empress Farah Pahlavi of Iran—as she was officially known until 1979, when her husband, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown and replaced by the Islamic Republic of Ayatollah Khomeini—was recently in New York to attend the opening of “Iran Modern,” a major exhibition of Iranian art from the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, at the Asia Society on Park Avenue. Tall and still beautiful at 75, she was the picture of elegance and dignity that evening, in a white silk dinner suit embroidered with black flowers, her champagne-colored hair pulled back and tied with a black satin bow for a nice schoolgirl touch. As always, she carried herself with the perfect posture and composed manner of royalty, yet made everyone she met feel as if she was delighted to see them—especially the artists whose work was in the show, though some of them had been fierce critics of her husband’s regime. Back then, the international press often referred to her as the Jacqueline Kennedy of the Middle East, not only for her glamorous style, but also for her commitment to historical preservation and her patronage of the arts.

Born Farah Diba on October 14, 1938, in Tehran, Iran, to well-to-do aristocratic parents, she was educated at private Italian and French schools in Tehran, before studying architecture in Paris. She was introduced to the shah at a reception at the Iranian Embassy in Paris in the spring of 1959, and he began courting her when she returned to Iran that summer. They were married in December, in a Shiite Muslim ceremony at the Marble Palace, in central Tehran. In keeping with traditional customs, the bride, wearing a gown designed by Yves Saint Laurent and a two-kilo Harry Winston tiara, set 150 caged nightingales free and was sprinkled with sugar by the queen mother. She was 21; the shah 40. He had been married twice previously, first to Princess Fawzia, the sister of King Farouk of Egypt, with whom he had a daughter; and then to Soraya Esfandiari. As these unions had failed to produce a male heir, both had ended in divorce. Ten months after her marriage, Empress Farah gave birth to Crown Prince Reza, followed by Princess Farahnaz in 1963, Prince Alireza in 1966, and Princess Leila in 1970.

The shah was a complicated and controversial figure who, on one hand, believed in the divine right of kings, and on the other, strove to make his country the most modern in the region, abolishing feudalism and emancipating women as part of his White Revolution of 1963. The empress herself was a symbol of how far women had come under her husband’s reign. She was the first Iranian queen to be named as regent in the event her husband died before the crown prince turned 20. She presided over a staff of 40 and was patron of 24 educational, health, and cultural organizations, traveling to the most backward parts of the country to inaugurate schools and hospitals. Under her direction, the government bought back hundreds of historic Persian artifacts from foreign institutions and private collections and built museums to house the recovered bronzes, carpets, ceramics, and other objects and antiquities.

In the early ’70s, the empress founded the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art and began assembling a collection of nearly 150 works, from the impressionists (Monet, Pissarro, Renoir) right through to the minimalists (Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Brice Marden), spending, she has said, less than $100 million. Today the collection, which also includes works by Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, van Dongen, Picasso, Braque, Miró, Magritte, Dalí, Pollock, Johns, Bacon, Hockney, and Lichtenstein, is estimated to be worth as much as $5 billion. The museum opened in 1977, but with the coming of the Ayatollah Khomeini two years later, these treasures were locked away in its basement vault, deemed unfit for Islamic eyes.

In 1976, Empress Farah commissioned Andy Warhol to do her portrait. They had met at a White House dinner given for the shah by President Ford—Andy told me afterward, “The shah was cool to me, but the empress was really, really kind and soooo beautiful.” Although I was editor of Interview at the time, my Factory duties also entailed selling Andy’s art, so I worked out the details with Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, Fereydoun Hoveyda, a former film critic who often invited us to his caviar-laden dinners, where one might find everyone from François Truffaut or Louis Malle, to Elia Kazan, Lena Horne, and Sidney Lumet. On July 5, 1976, Andy, his manager, Fred Hughes, and I flew to Tehran, accompanied by Nima Farmanfarmaian, a New York Post fashion columnist and the daughter of two well-known Iranian artists, Monir Farmanfarmaian and Manoucher Yektai. A dozen schoolgirls in gold brocade caftans greeted us at the airport and pinned pink roses to our lapels, before we were whisked off in a limousine to the Tehran Inter-Continental Hotel, where Andy immediately began ordering caviar from room service for only $10 a portion. The following night we found ourselves at a state dinner for Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan hosted by Iran’s Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda, the older brother of the ambassador. (Less than three years later, both host and guest of honor would be executed, Hoveyda during the revolution, Bhutto after a military coup.)

The Tehran we saw that summer was a growing, prosperous, modern city—just as the Iranian society we encountered was dynamic, affluent, and cosmopolitan. The very rich, a group that included a high proportion of Christians and Jews, lived in the hills on the northern side of town, near the imperial family’s Niavaran Palace compound. Their villas would not have seemed out of place in Bel Air—except for the Persian carpets beside the pools—and the women wore bikinis by day and haute couture by night. Closer to downtown, vast middle-class housing developments were under construction, including one by that pioneer of affordable American suburbia, William Levitt. Only in the old bazaar in poorer south Tehran did we see women in head-to-toe black chadors, and it was there that the sound of our American accents elicited the occasional ominous hiss from within the jostling crowds.

During the week we spent in Tehran waiting for Empress Farah to find time in her busy schedule to pose for Andy’s Polaroid Big Shot camera, I never once heard the word “Shiite.” Yet, by the following July, when she came to New York to receive a women’s rights award at a luncheon given by the Ecumenical Appeal to Conscience Foundation, hundreds of masked demonstrators were shouting, “Kill the shah!” outside the Pierre Hotel, and police on horseback struggled to push them back across Fifth Avenue. “This is too scary,” moaned Andy, as we rushed inside. In November, Andy and Fred Hughes went to President Jimmy Carter’s state dinner for the shah, where some 8,000 demonstrators surrounded the White House. By then, protests had begun in Iran, and the shah’s regime was coming under increasing criticism in the American press. So was Andy. A few days before the White House dinner, The Village Voice ran a photograph of Andy and Empress Farah on its cover, under the headline “The Beautiful Butchers.” Not long after, Andy’s old friend, Henry Geldzahler, the Metropolitan Museum curator who had just been named New York City Commissioner of Cultural Affairs by Mayor Koch, personally berated him for dealing with “the murderous shah.” That did not stop Andy from agreeing to do the shah’s portrait, when Ambassador Hoveyda asked him to in early 1978. As His Imperial Majesty would not be sitting for Polaroids, Andy made his silkscreen from an official photograph of the shah wearing a formal white military tunic with a gold-embroidered collar and epaulets. We were all set to go to the Shiraz Arts Festival in September 1978, where the portrait would be unveiled, when a telegram arrived from the Ministry of Culture. “Due to illegal manifestations by extreme xenophobic groups, we regret to cancel this year’s festival.”

The shah and the empress left Iran on January 16, 1979, and two weeks later, the ayatollah arrived in triumph, going on to become the Supreme Leader of “God’s government.”

For the next several months, the deposed royals moved from country to country—Egypt, Morocco, the Bahamas, Mexico—seeking refuge while under the threat of extradition and death from the new Iranian regime. In October, President Carter reluctantly admitted the shah to the U.S. for medical treatment; in response, Iranian militants seized control of the American embassy in Tehran, taking its diplomats hostage for what would become 444 days. The Pahlavis were then packed off to Panama and finally to Egypt again, where the shah died in July 1980, of cancer (lymphoma).

President Reagan allowed his widow and children to enter the United States in 1981, but life in exile has not been easy on the family. Princess Leila died of a drug overdose in London in 2001; Prince Alireza committed suicide in Boston in 2011. “The children were thrown from their gilded cages into the jungle at a very young age,” says a family friend, “and could not survive.”

These days, the former empress divides her time between Paris and Potomac, Maryland, where her son, Prince Reza, the once would—be shah, lives. We talked over tea at the apartment of her cousin Layla Diba, the former curator of Islamic art at the Brooklyn Museum and co-curator of “Iran Modern,” which is on view through January 5.

FARAH PAHLAVI: I’m happy that there are exhibitions about Iran in this country at this time. It’s good for Iranians who are in America to see that their country has been honored, and also for Americans to know a little more about Iran. The exhibition [earlier in 2013] of Cyrus the Great’s Cylinder at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery in Washington was a great success. The director told me, “We didn’t ever have a show with so many viewers and press.” And the exhibition now at the Asia Society about Iranian modern art is interesting because, after what the American people have seen in the news about what has happened in Iran, it’s good for them to see another image of our country and our people.

BOB COLACELLO: The period the Asia Society exhibition covers—the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s—was the time you were empress, right?

PAHLAVI: Yes. I got married in 1959. And I was lucky, in a way, because I came in a period when Iran was going ahead in many fields—industrial, cultural, educational. I always say I am grateful to my husband, because he supported me and guided me and helped me to be able to do things in the fields I was interested in, as a person and also in my position. I remember the first time he asked me to marry him. He said, “As queen, you will have a lot of responsibility.” And I said yes, because in my youth, I was a girl scout, and in school they were teaching us to serve others, to help others. But I couldn’t imagine the scale of the work! It took me a few years to know about the problems and to find ways to help. I’m also grateful to all my compatriots who came to see me, ladies and gentlemen, explaining to me that “We need this” or “We need that”—in social welfare, for example, for children who were sick, or mentally ill, or underprivileged, or who couldn’t see, all sorts of this kind of thing, but also in education, which was the most important thing for our country, and in culture. I was interested in culture. I loved culture. I wanted to help in any way that I could for the preservation of our ancient and traditional culture. Not just in terms of architecture, but art and literature and poetry and handicrafts. I was also interested in contemporary art and I wanted to support Iranian artists. I believe my interest started in the early ’60s, when I first went to the Tehran Biennial that the Ministry of Culture had organized for Iranian painters. And then, slowly, there were one or two galleries—private galleries—which would show Iranian artists. I really admired their work, and I myself was buying. And also I was trying to encourage those who could afford to come with me and to buy, because Iranians who were wealthy at the time were more interested to collect ancient Iranian art, and not so much contemporary. I encouraged the Ministry, which had a budget for decoration, to be involved, too—I said instead of just spending it on ugly furniture, you could order a painting or a sculpture from an artist. I did the same with mayors of cities. And slowly, it took off, and there were many exhibitions and many collectors, and it was a period when we really had great artists. So I’m very happy that Asia Society is showing that period.

I REMEMBER THE FIRST TIME HE ASKED ME TO MARRY HIM. HE SAID,‘AS QUEEN,YOU WILL HAVE A LOT OF RE SPONSIBILITY’ . . . BUT I COULDN’T IMAGINE THE SCALE OF THE WORK Farah Pahlavi

COLACELLO: Did these artists tend to be more abstract or figurative?

PAHLAVI: Some were figurative, most were abstract. Some were inspired by Iranian handwriting, calligraphy. Some were inspired by Iranian culture, others by contemporary European and American art. Some of them studied outside the country. France had a program of selling apartments for artists, so we bought two or three apartments for Iranians. The artists could come there and stay for two or three years. To tell you the truth, I had forgotten about this until a few years ago, when two Iranian painters—ladies—e-mailed me to thank me for these ateliers. We were also participating in exhibitions outside the country—in France, for example. It was to the point where I would ask my husband, instead of paying money for the transport of the art, to put it in military planes that had to go sometimes anyway. We were trying to get everybody’s help for that.

COLACELLO: Were there any good art schools in Tehran at the time?

PAHLAVI: We had a school of architecture at Tehran University and there was a part for art.

COLACELLO: You studied architecture in Paris.

c: Yes, at the École Spéciale d’Architecture, which was a good school. I stayed there for two years and, even now, I think I chose the right thing. I liked it. Of course, I didn’t become an architect, but later on in Iran, I had a lot of contact and discussions with architects because Iran was developing, and I felt we shouldn’t destroy the past and copy completely the West, which is the problem in developing countries. You know, they build new buildings that have nothing to do with the spirit of the area or the climate or the color. So I created a foundation to honor those Iranians who built modern buildings but who were inspired by the past.

COLACELLO: When did you establish this foundation?

PAHLAVI: It must have been in the mid-’70s. In Iran, as in all developing countries, they wanted to copy the outside world, without knowing what was good for our own country. But slowly, that was changing, and those who could build beautiful houses had Iranian artisans do the work.

COLACELLO: You were involved in the building of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art and worked closely with the architect, Kamran Diba, right?

PAHLAVI: Yes. I thought that we also needed a museum. So, when the price of oil went up in the early ’70s, I asked my husband and the prime minister. I said, “It’s now or never to buy some of these things.” Of course, we had a fantastic—and very old—museum for ancient Iranian art. We started the Carpet Museum of Iran, and the Negarestan Museum, which showed paintings and objects from the Qajar period, which was the dynasty before the Pahlavis. We also started a museum for ceramics and glassware, pre-Islamic and Islamic, in a very old building—again, I wanted to preserve the old buildings, not to destroy them and build something new. The most important thing was the contemporary art museum. I remember I went to an exhibition somewhere and one of the artists, an Iranian lady, said, “I wish we had somewhere that our paintings would stay forever.” So this idea came to me. I said, “She’s right, we should have a place to keep them, and not only Iranian art works, but also of foreign artists.” These two museums, for carpets and for contemporary art, were built in a park, because I was thinking that people come and go in a park, and they will go through the museums. Mr. Kamran Diba, my cousin, was the architect, and built a beautiful, modern building for the Museum of Contemporary Art, inspired also by ancient Iranian architecture, and not too high, because we didn’t want to destroy the view of the park. We had the help of two American curators, Donna Stein and David Galloway, who helped acquire the collection. Of course, when galleries in New York and Europe found out that we were interested, they started sending us material. I must say, it’s a great collection. When I think of the price we bought this collection for in the ’70s … The museum was inaugurated in 1977, and I’m happy that it’s still there because I was really very worried after the revolution about what would happen to this contemporary art. Fortunately, the new director, who had been president of the school of art in Tehran University, really managed it well, and all the staff worked very well to put everything in the basement.

COLACELLO: In storage.

PAHLAVI: In storage, yes, with everything named and numbered. Of course, after the revolution, they didn’t show that collection—they only showed revolutionary paintings. But within the last several years, the museum has shown some of the contemporary paintings—not all of them, because some, they said, were un-Islamic—and I was happy because people got to see what they have. I will never forget the e-mails I’ve received from Iranian artists. Some of the older artists, of course, we are in touch, we talk to each other. But young Iranians sent kind e-mails, telling me, “You were the one who supported art.” It touches me very much. A woman from Tehran said, “When I went and stood in front of a Rothko, I had tears in my eyes.” Of course, the only thing the museum did that was not right was the exchange of a de Kooning [Woman III] for the remaining pages of what we call the Shahnameh, the “Book of Kings” [a manuscript of 258 Persian miniatures compiled in the 16th century; Arthur Houghton Jr., the Corning Glass Works heir, purchased it from the French banker Baron Edmond de Rothschild in 1959]. It’s a long story. Those pages were from the Houghton “Book of Kings.” Mr. Houghton wanted to sell it to us in 1976 for $20 million, so we could not buy it. And then he tore some of the beautiful miniatures and gave them to the Metropolitan Museum, and some he put on sale. I asked a great collector what those were worth, and he said $6 million. So I thought, if the Islamic Republic is interested to have this, they can pay $6 million. But they exchanged it [through London dealer Oliver Hoare and Zurich dealer Doris Ammann, in 1994] against this de Kooning. And then I saw in The New York Times that the de Kooning had been sold to Mr. David Geffen for $20 million. And Mr. Geffen has sold it [in 2006] to another collector [Steven A. Cohen] for more than $100 million, I have to tell you, when this happened, I called the museum.

COLACELLO: You did? Were they stunned to receive a call from you?

PAHLAVI: No, I didn’t say who I was. I said, “I am a student in art and very much interested in this museum.” Stupidly, I forgot it was Friday—Friday is a holiday in Iran. So the man said, “Sorry, it’s closed. Call tomorrow.” The next day I called, told the same story, and then someone important came to the phone. I said, “You know this is the artistic capital of our country. You should not exchange it.” He said “Madame”—I don’t know how he called me—”they forced us.” But so far, so good—nothing else like that has happened. I am always afraid that when they speak about this museum in the press, people get interested. I know that some big collectors are interested.

COLACELLO: To acquire works from the collection?

PAHLAVI: To acquire, yes.

COLACELLO: I was told that when you were putting the collection together, you were advised by and dealing with Tony Shafrazi and Leo Castelli. Is that correct?

PAHLAVI: Yes, Tony Shafrazi had a role, and also Castelli, the Greek dealer Iolas, and Beyeler in Basel. And then many years ago, I saw Mr. Beyeler in Paris, and I said, “Mr. Beyeler, I heard that you’re interested in some of the paintings in Tehran. Please, there are more paintings outside. Don’t!” He said, “No, no—they’re too expensive for me now.”

COLACELLO: It must be frustrating, though, to know that this wonderful collection is there, but no one can see it.

PAHLAVI: No, I’m happy that it’s there because all this belongs to the nation, and hopefully, there are people who will help it stay there forever.

COLACELLO: You were also very involved in starting the Shiraz Arts Festival, for music, dance, drama, poetry, and film, in 1967.

PAHLAVI: Yes. You know, Iran was considered to be between East and West, and we thought about the idea and we discussed it with people in those fields. There was already the Baalbeck Festival in Lebanon, and we didn’t want to do the same thing, so we decided that we would have a festival that showed both traditional works from all over the world along with the contemporary and the avant-garde. We formed a board of trustees and got our Ministry of Culture involved. We thought Shiraz would be the best place, because it’s a city of culture and art, and to do it in September, when the schools are not yet open and we could use the dormitories of the universities for people coming to the festival. So we started in Shiraz, not only in the city but also in the ruins of Persepolis outside the city. We had great artists coming to Iran from all over—Japan, Africa, Europe, America.

COLACELLO: I remember there was talk in the art world in 1972 about Robert Wilson putting on his play Ka Mountain there. People couldn’t believe it, because it went on for 168 hours—without interruption.

PAHLAVI: Yes, it was unbelievable. Even in America, they didn’t know so much about Robert Wilson then. Unfortunately, we had to stop the festival after 1977.

COLACELLO: I know, because Andy Warhol and a group of us—including Fred Hughes, Paloma Picasso, and São Schlumberger from Paris—were invited to the 1978 festival. Andy had done your portrait, and then your husband asked to have his done, and it was going to be unveiled in Shiraz. But we all received telegrams saying, “Due to illegal manifestations by extreme xenophobic groups, we regret to cancel this year’s festival. But we will invite you again next year.” That never happened. But I never forgot the wording of that telegram.

PAHLAVI: Awful. By the way, French television showed a film of some of the paintings in the basement of the museum, and my portrait by Andy Warhol was cut with a knife.

COLACELLO: Weren’t several of your portraits there?

PAHLAVI: I think there were two of my husband and two of me in the museum. And I had one in the palace—I think it’s still there. What’s interesting is that recently they have published a book called The Perfume of Niavaran Palace. The book has pictures of all of the art I personally acquired in it, and I’m very happy that they’re all there. Of course, some of them belonged to the Court. Also, in the film from the museum, they were pulling some of the paintings out, and one was Andy’s portrait of Mick Jagger. I don’t think it was a painting actually. Maybe it was a print.

COLACELLO: Was the shah interested in art? How would your husband react to something like Bob Wilson’s play?

PAHLAVI: He didn’t see those kinds of things. He liked more traditional music and also comedy—in movies and plays. I was the one going to the festival. He only came once [in 1973] when Maurice Béjart did something fantastic called Golestan in the ruins of Persepolis, with Persian music and songs, and his greatest dancer, Jorge Donn, who was fantastic. It was the first time my husband came to the festival. The other years, he didn’t come. He didn’t have time. He had other things to do.

COLACELLO: I’ve read that President Kennedy went along with Jacqueline Kennedy’s idea of having classical musicians performing after dinner at the White House, but he would have preferred more Hollywood-style entertainment.

PAHLAVI: Well, people have different tastes.

COLACELLO: Some historians and journalists have written that the huge and extravagant party that your husband and you put on in Persepolis in 1971 to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great was a mistake. They say that it contributed to the growing disenchantment with the monarchy within Iran that culminated in the revolution eight years later. Looking back on it now, do you think that’s true?

PAHLAVI: Looking back, many things are seen differently. Even those who were against us are thinking differently because those who were against, exaggerated. I must say that there were a few things that we could have done otherwise—and things that even I was not happy with but which were already done. But you know, if the Cyrus Cylinder can be exhibited in Washington and go to cities all around America, then it’s because the ancient history of Iran was made known to the world at that time. People have forgotten the positive sides of those celebrations, and all of the committees that were formed in almost every foreign country, and all of the exhibitions, concerts, books, articles, and conferences about Iranian history that came out of them. A year or two ago, an Iranian television station in London made a film about these festivities, and they interviewed me, as well as the person who was responsible for the organization of it. They had such a positive reaction from Iran, because people there saw the respect the whole world had for Iran back then, and all the world leaders that came to Persepolis [Haile Selassie, Tito, Imelda Marcos, Prince Rainier and Princess Grace, among many others]. The cost of the celebration was exaggerated and other things were invented, but when people are against you anyway, they believe everything. Now, though, in Iran, they actually asked to have this film shown again. For Iranians today, it is interesting to see, for example, the uniforms and clothes of Iran from 2,000 years ago and all the work behind the celebration. So, yes, now people look at things differently. I especially remember when my husband, in his speech in front of Cyrus the Great’s tomb, said, “Sleep easily, Cyrus, for we are awake.” Some people made fun of that. But as I said then, he meant that the Iranian people were awake—and they are! Today, and for many years now—and as I say this, I have goose bumps—on our New Year, the 21st of March, lots of young Iranians, old Iranians, women and men, go in front of the tomb of Cyrus and say something which rhymes in Persian: “Iran is our country and Cyrus is our father.” These are Muslims—good Muslims—but this Iranian identity is becoming stronger and stronger among Iranians. And what is fantastic is that, despite all the pressure and opposition, many Iranian artists continue to create in Iran—and there are many artists.

COLACELLO: Is there an art scene in Tehran?

PAHLAVI: Well, some artists exhibit outside the country and do some shows in their homes, because their work is political, and they don’t allow that. You know, when these people came to power, they forbade even traditional music. But now there are fantastic traditional groups in Iran and they come outside and have concerts. There are so many cultural things in our country that are so strong that they cannot destroy them. To give you an example, when they first came to power, they wanted to destroy the statue of Ferdowsi, the poet who wrote the “Book of Kings” [in the 11th century]. But it was so inside people that they couldn’t do it—people didn’t allow them. It was to the point that one of the presidents who came to America, Mr. Khatami, referred to Ferdowsi’s poetry in his speech at the UN. They also wanted to forbid the 21st of March, saying it was a pre-Islamic celebration. But it’s so much inside the people that they are celebrating it themselves. There are things that are stronger than them.

COLACELLO: It reminds me of how the Taliban blew up the gigantic sixth-century Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan.

PAHLAVI: Can you believe it?

COLACELLO: When I saw that, I thought, These people are insane.

PAHLAVI: You know, it’s not useful to think back, because I always keep reminding myself that Einstein said, with all the energy of the world, you cannot go back one second in time. But I thought, If one of these religious people had only said, “Listen, those who are not Muslim are transformed into stone. So let this be an example.” You know, something like this. Sometimes it works.

COLACELLO: Right, they had to spin it in the right way. But to destroy historical monuments like that … I can understand wanting to have a purely Islamic regime now, but that doesn’t mean you should obliterate what came before.

PAHLAVI: They’re crazy people, really.

COLACELLO: What is your life like now? Where do you live?

PAHLAVI: I’m between Paris and Maryland. And I’m busy always, with all the e-mails I receive and sometimes with interviews that they ask me for. I try to follow what’s happening and to be in contact with some Iranians. So I get busy. Sometimes it is too much because I don’t have the staff to do all this.

COLACELLO: Do you follow the contemporary art scene?

PAHLAVI: Yes, I do, though, now, not as much as I used to—really, I don’t have time. But especially if Iranians have a gallery and they want me to be there, or an Iranian artist wants me to come to her or his show, I try to do it. You know, artists go through me to find someone who can show their work, so if I know someone in a gallery in Paris, I can call them and I say, “There is so-and-so, perhaps you can see his or her work and possibly exhibit it.” So I try to help them in any way I can, by introducing them to some people or by being present at their openings, and maybe it appears in the press—I do this kind of thing, if I can be of help.

COLACELLO: I was amazed to hear that Monir Farmanfarmaian, whose painting is on the cover of the “Iran Modern” catalog, has become a major artist in Iran. Andy and all of us at the Factory in the ’70s were good friends of her daughter Nima. And I remember she was not having much success.

PAHLAVI: Yes, but now, with her mirror work, she is. What’s interesting is that there are many collectors outside Iran for Iranian artists and also many collections inside Iran. There are many galleries, apparently.

COLACELLO: So, it’s like you said, they can’t really control it.

PAHLAVI: No, they cannot stop culture. And sometimes when there is pressure, artists become more creative, whether it’s poets or painters or filmmakers. Look at the movies coming out of Iran.

COLACELLO: And art becomes more vital because it may be the only way people can truly express themselves. They can’t make political statements, so they have to channel more meaning into paintings or music or literature. You saw that in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, especially with novelists or poets. Do you have hope that there will be real change in Iran?

PAHLAVI: I have hope. I never give up hope because I know that there is so much oppression and these people will not leave just like this. But the majority of Iranians now are young—below 30 years of age—and with the Internet, Twitter, Facebook, television, they see. They are educated, they are intelligent, and also they learn more about what was Iran, and what Iran could have been 30 years later with the oil revenue, with the intelligence of its people. It’s heartbreaking when I hear that there is so much drug addiction in Iran because young people have no hope or become depressed because of all the restrictions of their lives. Even prostitution among very young people! Children begging in the street … Of course, we were still a developing country, and there were some areas that still needed so many things to be done. But back then, we had possibilities. Fortunately, the parents of these young people tell them what we were, and they learn about all the nonsense that has been said during the revolution and that continues to be said. So they know what was there, and sympathy for my late husband is growing more and more. When they talk about him now, they say, “May god bless his soul.” And they say, “During his time, the price of chicken was this, and now it’s that …” Of course, the sanctions have added to people’s suffering. But even before the sanctions, people could not eat meat for a week or 15 days. It’s unbelievable. When I hear that sometimes people steal bread from each other—I mean, how is it possible in a city like Tehran? Yes, the population has doubled, but this regime, in the name of religion, has done so much harm, told so many lies, and there is so much corruption. It cannot stay like this. Iran has been invaded in its history by different civilizations, but always Iran rose from her ashes. And this time it will happen, too, because it’s important for Iranians above all, but also for the Middle East and the rest of the world, that Iran will be a country that is the way it should be.

COLACELLO: What are your thoughts about the Arab Spring and what is going on in the Arab world today?

PAHLAVI: When you see what’s happening now in this area, it’s very strange and very worrisome. There were some fanatical groups in different Muslim countries, but I think it all started with Khomeini. I mean, also, this war has been started between the Sunnis and the Shiites.

FRENCH TELEVISION SHOWED A FILM OF SOME OF THE PAINTINGS IN THE BASEMENT OFTHE MUSEUM, AND MY PORTRAIT BY ANDY WARHOL WAS CUT WITH A KNIFE.Farah Pahlavi

COLACELLO: In Syria and Iraq?

PAHLAVI: In Syria, everywhere! This happened among the Christians, between the Catholics and Protestants, hundreds of years ago. It’s ridiculous. But I want to be hopeful because I know the reaction of young people in Iran. They want to have a better life. Not only young people, but workers, journalists, intellectuals. I want to consider it like the period of the Inquisition in Europe, and then there will be a period of light, of the Enlightenment. It will come because for a country like Iran, with so much culture, it is not possible to go on in the dark like this. Of course, it’s worrisome, all these movements of fanatics in the name of religion doing so much harm. There are many Iranians who were religious and who don’t want to talk about religion anymore because of these people.

COLACELLO: Were you and your husband religious?

PAHLAVI: We were Muslims, and we are still. But, you know, I was asked once, “Did you practice?” I said, “I practice human rights,” which is also in every religion—to be good, to be helpful, not to kill, not to lie, to be generous. These are the values.

COLACELLO: But then people would say that your husband had thousands of people imprisoned, and his secret police, the Savak, were brutal in crushing political dissent.

PAHLAVI: Yes, of course, they say that, and they exaggerate. I say there were things where my husband was not aware of what was happening, and even if there was one person imprisoned wrongly, it’s not right. But you have to consider all the Communists we had in Iran 30 years ago and the threat from the Soviet Union. And now there are people who say, “Why didn’t he stay and put the revolution down?”—which would have meant killing people, and my husband said he never wanted to keep his throne on the blood of his people.

COLACELLO: So before the revolution, your husband was more worried about Communists than the mullahs?

PAHLAVI: Yes. I mean, there were Communists who were directly attached to the Soviet Union. So in Iran we were more worried about a Communist takeover. Even our allies thought the same way. The mullahs, the religious people, were free to go into their mosques and say what they wanted to say. I think many people—the Communists especially—thought that if Khomeini comes and the shah leaves, then they will take over. None of them believed in religion anyway, but they went into the streets with their veils and so on. Some of these people who participated in the revolution have the courage to say now, “We made a huge mistake.” But you cannot believe that even some intellectuals said they saw the picture of Khomeini on the moon …

COLACELLO: On the moon?

PAHLAVI: On the moon!

COLACELLO: Under your husband’s rule, there was greater religious freedom, and Christians and Jews were more free to practice their faiths.

PAHLAVI: Yes, exactly. Many Jewish Iranians left after the revolution. I remember, in school, I had Christian friends, I had Jewish friends, and there was no discussion.

COLACELLO: Do you travel to the Middle East these days?

PAHLAVI: The only place I have been was Jordan. I went a few years ago for the wedding of Queen Noor’s eldest son. And I go to Morocco still sometimes.

COLACELLO: I was very sorry about the death of your friend Claudio Bravo [the Chilean hyperrealist painter, in June 2011, of complications of epilepsy]. You often stayed at his houses in Marrakesh and Taroudant, no?

PAHLAVI: Yes. I really miss him. It’s such a pity. He was a fabulous painter and so hardworking. We knew that we could not disturb him until 6 o’clock in the evening. Every morning, he would work and … Anyway, so sad.

COLACELLO: Do you still believe that monarchy is a viable system in today’s world?

PAHLAVI: I think so, because monarchies are above political parties. Sometimes political parties do things that are to the disadvantage of the country because they want to beat the other party. In Iran, where we have different religions and ethnic groups, it was a unifying factor. When you see what happened in Iraq after the king was gone, and what happened in Afghanistan, in Egypt, in Libya, in Yemen … You know, Americans accept very well the British monarchy, but the rest, they don’t know much about. But some of the monarchies in Europe are more democratic than some of the countries that are republics. I mean, when you think of Sweden, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands. So it’s up to the people to decide what they want. And this is what my son says. He’s active in any way he can be, and for 30 years he has said, “Let’s get together and get rid of this system.” And hopefully, one day, it will be up to the people to decide if they want a constitutional monarchy or a republic of some sort.

COLACELLO: Are there artists in the Asia Society exhibition that you have a particular interest in or whose work you have in your collection?

PAHLAVI: I loaned two pieces of Bahman Mohassess. Unfortunately, he passed away [in 2010, in Rome]. I was in touch with him even near the end. I also like the work of the sculptor Parviz Tanavoli, who is becoming—touch wood—so famous now. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has bought one of his works, and also, I believe, the British Museum.

COLACELLO: Do you like Shirin Neshat’s work? She’s probably the best-known contemporary Iranian artist in New York.

PAHLAVI: Yes, it is interesting.

COLACELLO: Would you consider yourself a feminist?

PAHLAVI: Feminist not in the sense that if a man opened the car door for me, I would say no. In that way, no, I am not. But I believe in freedom for women to have equal rights—the right to work, the right to hold high positions, the right to take custody of their children after divorcing. All those laws, we had in Iran. Unfortunately, many of them have been changed.

COLACELLO: These were laws that were instituted under your husband’s regime?

PAHLAVI: Yes, during our time. The only thing they couldn’t change is women’s right to vote and to get elected. That happened in 1963. Before then, women in Iran could not vote.

COLACELLO: In other words, in 1963, women were legally emancipated and given the right to vote.

PAHLAVI: Yes, and they still can vote. They couldn’t change that because Iranian women are very courageous and active, even with all the oppression. But, for instance, polygamy was forbidden, women could reach the highest positions. During our time, the woman who won the Nobel Peace Prize [in 2003], Shirin Ebadi, was a judge. But after these other people came, they forbade her to be a judge because they said a woman is not just enough to judge. There were many laws in favor of women. They have changed many, and it’s really terrible. Anybody can insult you in the streets now. They’re obsessed with women. But Iranian women never give up.

COLACELLO: I sometimes wonder if, in America and Europe, we haven’t gone too far in the opposite direction—in excluding religion from the public sphere and looking down on people who are religious. I think things like banning Christmas trees and Hanukkah menorahs outside schools, for example, have only created a reaction and encouraged the rise of fundamentalism.

PAHLAVI: Yes, it’s better not to exaggerate on one side or the other.

COLACELLO: Because religion can be an important factor in teaching children morals and ethics and manners—the basic values.

PAHLAVI: Exactly, basic values, not fanatical things, like they do, and not only in Iran. Fanaticism exists in every religion, whether Christian, Jewish, or Muslim.

COLACELLO: We live in an interesting but kind of crazy time, I think.

PAHLAVI: It is. I hope in the end there will be a solution for the world, because we have advanced in so many ways, and still the world has so many different problems. By the way, there are many Iranians working at NASA. One of the engineers involved with the spaceship that went to Mars is an Iranian. You know, your country has given the Iranians who are here the opportunities to be successful in every field, whether it’s business or science or art. So one thinks that it’s a pity that these successful people cannot be successful in their own country and use their talent and knowledge there. Some of them are, actually, and it’s very touching. Some Iranian doctors from Europe and America go to Iran and operate for free or teach medical students there. The other day, I met a gentlemen who is helping to protect wildlife in Iran. It’s good that many of them don’t forget about their country. It’s important.

COLACELLO: One last question: Do you think that in the months before the 1979 revolution, as the unrest in your country became more and more widespread, the American government could have done anything differently that would have helped keep your husband in power?

PAHLAVI: You know, it’s a long story. There are many things coming out from archives that have been opened now, but which we didn’t know those days. They say that the Americans—I have no proof—were worried about the Communists taking over Iran, and so they wanted to create a Green Belt of Islam to prevent that. We know now that the last American ambassador was meeting with the opposition because documents about that came out in Iran. It was a mixture of everything. There were problems we had with America, with England, with France. But also with our own people. We cannot blame only outsiders.

COLACELLO: I found it astonishing that President Carter went to Tehran in 1977, for New Year’s Eve, and proclaimed in his toast at your dinner that Iran was America’s best friend in the world.

PAHLAVI: He also said it was “an island of stability.” But then he started his program of human rights. Okay, but what next? Why, after the shah of Iran left, was there no speaking about human rights anymore. Well, let’s say, okay, at first, it was a revolution, and they were waiting to see what happens the second year. But after the second year, what happed in Iran? My god! Why then, did nobody speak about human rights anymore? It’s normal that countries work for their own benefit, political and economic. You cannot expect a foreign country to be more Catholic than the pope for you. Or in Persian we say, “The bowl hotter than the soup.” It’s up to us—our nations—to know what we want and where we are going. And not to just sit and think, “Well, America should do this, or England should do that.” I hope this is a lesson for us in the future and for many countries. Those who came out in the streets of Tehran—the Americans didn’t bring them in the streets. But it was a mixture of inside and outside.

COLACELLO: Well, I hope for your country’s sake—and for you personally—that someday you return to Iran, even if just as—

PAHLAVI: An ordinary person.

COLACELLO: Yes, just to be able to go home.

PAHLAVI: You know what keeps me going? Of course, I have hope. But really it is the e-mails I receive from my compatriots, young ones, who have been born after the revolution, who have heard so much. It’s so encouraging. Sometimes, I call them, which gives them courage and energy. So I hope that things will change, because it’s a pity that a country like Iran is not where it should be, or where it has been historically. It’s important for Iran, for all of the Middle East, and also for the rest of the world.

COLACELLO: Yes, because I think if the ayatollahs get the nuclear weapons, it will be very frightening.

PAHLAVI: There are many people inside Iran who say, “We don’t have enough to eat. Why do we need a nuclear bomb?”

COLACELLO: I would be afraid if they would share it with Venezuela because they have such close ties, even now after Chávez’s death. That would be like another Cuban missile crisis.

PAHLAVI: I know. I hope not. I hope before then, we get rid of them.

BOB COLACELLO IS A SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT FOR VANITY FAIR AND THE FORMER EDITOR OF INTERVIEW. HIS 1990 BOOK HOLY TERROR: ANDY WARHOL CLOSE UP,WILL BE RE-ISSUED IN MARCH.