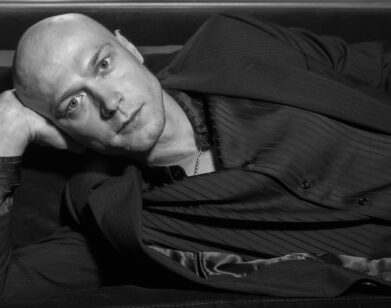

Andrea Pitzer and the Original of Nabokov

ABOVE: ANDREA PITZER. IMAGE COURTESY OF ULRIKE WILSON

History shapes us all. Andrea Pitzer’s The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov (Pegasus) explores the famous writer’s life and how his times impacted his work. When his idyllic childhood was shattered by the Russian Revolution and his family was forced to flee, Nabokov’s life changed dramatically. Then Nabokov lost his father, who had illuminated his young years with literature and art. As an adult with a Jewish wife and son, he was terrorized in a Germany under Hitler’s rule. Pitzer eloquently argues that persecution, innocence, and loss would become themes Nabokov explored in many of his works, because of the history he witnessed. Smart without being didactic, poetic, engaging, and fresh, Pitzer pulls information from newly declassified intelligence files and recovered military history. From Tsarist courts to Nazi film sets to wartime Casablanca, Nabokov’s history is one full of poetry, passion, and fame—but also sadness, sensitivity, and pain. We sipped sodas with Pitzer at Soho House and spoke about her fascination with Nabokov, concentration camps, Shirley Temple, Lolita, and the celebrity it inspired.

ROYAL YOUNG: Where did your fascination with Nabokov come from?

ANDREA PITZER: I had read Lolita when I was a teenager and frankly, was put off by it. It was incredible storytelling, but I so identified with Lolita and was becoming this new feminist. It was disturbing and very hard to take what was happening to her. I didn’t condemn it, but I didn’t to delve too much into it. I always felt like I had never given Nabokov a real shake. Years later, an obsession was born.

YOUNG: What obsessed you the second time around? Had you grown past the discomfort you initially felt?

PITZER: I think the book is supposed to be disturbing and uncomfortable. I had gotten better about sorting out stuff that was more worth my time. I had become a better reader, though I was still uncomfortable with a lot of things in it. I just dropped everything and started researching Nabokov. The Widener Harvard library was perfect—you can wander the stacks, and it’s huge, it’s like the Pentagon. I would bring home trash bags full of books. I couldn’t help myself. It wasn’t a choice.

YOUNG: [laughs] That’s the best kind of obsession. How does the feeling of persecution play out in Nabokov’s work and life?

PITZER: In his life, he went from a perfect, idyllic childhood with 50 servants and an unbelievably culturally rich existence in which he had access to his father’s library, which had its own librarian, to becoming a refugee from the war in Europe. He arrived in the United States weighing something like only 124 pounds, and he was a tall man. Then, when he wrote Lolita, he was culturally persecuted for his writing. Graham Greene was one of his best defenders.

YOUNG: I love Graham Greene.

PITZER: Well, he had his own weirdness with Shirley Temple. He criticized the use of the Shirley Temple in movies as sort of being sexually provocative in these kiddie movies she was in. He said something about her well-toned rump and was roundly persecuted for the whole way it came out. Thought it was really a criticism of Hollywood. He was probably feeling sympathetic to Nabokov. What I suggest in my book is that a lot of Nabokov’s villains are anti-heroes that are victims of history, and that affects their choices.

YOUNG: One of the things that is so uncomfortable about Lolita is that she is not an innocent herself. She comes to Humbert deflowered and is very manipulative, savvy, and aware of her power. If she was just a complete victim, it would be easier to write it off. Because she’s so rich and layered, it’s more uncomfortable.

PITZER: That idea of her as knowing and choosing what she was doing has been embraced by some people. I don’t buy it. I think she’s an incredibly rich character and the book would be lesser if Nabokov had made her this completely unknowing innocent. It almost makes what Humbert does to her more powerful. It’s one thing to be a pre-teen and sexually curious or active and it’s another to have a man basically kidnap you, drive you across the country and bribe you. She cried herself to sleep every night. You see the rupture, the lost mom, the dislocation, you see her thinking about dying alone.

YOUNG: When did your interest in history come into play in terms of relating to Nabokov as a figure?

PITZER: Pale Fire is what first started my obsession. I had studied Russian history and was amazed by how much Pale Fire seemed to be a Cold War novel. I started researching further and further and eventually found a lot of places where Nabokov brought in history. I argue in the book that concentration camps and their history affected Nabokov’s life profoundly, and that was reflected in his writing.

YOUNG: It’s so crazy that the persecution keeps popping up in terms of his awareness of the world.

PITZER: He could be a very cutting man. He was the master of the one-line barb, but he also had this tremendous sensitivity. Marrying a Jewish woman in the face of the anti-Semitism in Russia and the things he had seen in Nazi Germany heightened his sensitivity a lot. Also, the loss of his father was tremendously traumatic, and that shook the foundations of this very secure childhood. Suddenly you had the Russian Revolution, his family fleeing, and then his father is assassinated. He learned in a very narrow space that the world could come apart and developed a tremendous empathy for people who had been through that.

YOUNG: What about his fascination with faded fame? What was his relationship to being a celebrity?

PITZER: He got notoriety, but he wasn’t really famous until Lolita the script. Once there was this scandalous book and the movie rights had sold, then he is fodder for the late-night monologues and gets really huge. At that point, you see him beginning to struggle with how to be that really public person. It seems increasingly over time, the answer was to close Vladimir Nabokov the person off and create this façade.

YOUNG: What was the difference between the person and the façade?

PITZER: [laughs] That could be the subject of many, many books. He wanted to control his life the way he controlled his books. In some ways as an adult, he tried to rearm himself with some of the protections of his childhood: to not be vulnerable to the world.

THE SECRET HISTORY OF VLADIMIR NABOKOV IS OUT NOW.