How Adam Levin Follows Instructions

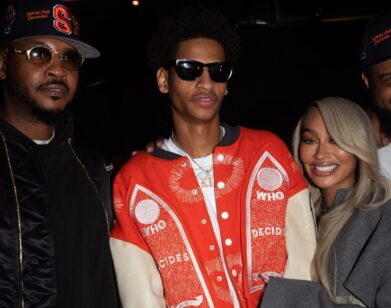

ABOVE: ADAM LEVIN. IMAGE COURTESY OF RENEE FELDMAN

Adam Levin’s last novel, The Instructions, made a big splash in 2010, and his new collection of short stories, Hot Pink, is poised to follow suit. The Instructions is an expansive novel that follows a 10-year-old boy who is anything but ordinary and, also, by the way, may or may not be the messiah. Hot Pink contains ten smaller, but no less surprising, stories. They are wacky, slapstick, and fully charming—it’s no surprise that Levin says he wishes he knew his characters in real life. You will probably wish the same thing.

We spoke with Levin about disregarding word count, David Foster Wallace, coffee versus tea, and identifying a fundamental decision: hang out with girls or save the world.

CLARE STEIN: Your last novel The Instructions spanned four days and 1030 pages. Hot Pink is a collection of short stories. How did the constraints, or—for a lack of a better word—the shortness, of the short story affect you?

ADAM LEVIN: I don’t think it did, to be honest. The novel and the short stories—I wrote them to the length they demanded. Anything I start, I don’t know how long it’s going to be. I write it until it’s finished. Within the collection, the longest story is 13,000 words, and the shortest one is probably 175 words, but it’s not about word count.

STEIN: Is there one story or character in Hot Pink that feels like a favorite child?

LEVIN: To a degree, they all do. I wrote them over a fairly long period of time. I think any story that I finish, I end up liking the characters in that kind of cheesy, writer’s-affection-for-his-characters way, because I wouldn’t have stuck with the story if not. They all have different aspects to them that make me wish I knew them, or something.

STEIN: Have there been a lot of writing exercises where you have started and not had any affection for a character, and so abandoned them?

LEVIN: Endless ones. Oh yeah, a ton. I delete almost everything that I write.

STEIN: The Instructions is about a 10-year-old Jewish boy who might be the messiah. How did this character come to you?

LEVIN: It came to me—I don’t know anything comes to me! But when I was a kid that was definitely the thing that I thought about. I think a lot of Jewish boys in Hebrew school thought about that. When you’re told there’s a messiah born in every generation and you go, “Maybe I’m that guy! I hope I’m that guy!” And then you meet girls and decide you’d rather hang out with girls than save the world.

STEIN: That’s a decision I guess every young person has to make at some point.

LEVIN: Exactly. Save the world or hang out with girls. That’s a fundamental question.

STEIN: What do you think of being called a Jewish writer and your writing being called Jewish writing?

LEVIN: I’m Jewish; I’m a writer. It’s not incorrect to call me a Jewish writer. The idea of Jewish writing is something that I don’t get offended by, but I don’t think is accurate. That’s used to imply that your writing is specifically for a community, with that modifier. I am definitely not just writing for Jews. I am writing for English speakers.

STEIN: There’s a Philip Roth cameo in The Instructions. Have you ever heard from Roth about that?

LEVIN: I have not. I wish; I wish. I have never met from him, never heard from him. Nothing.

STEIN: Speaking of other writers, you’ve been compared to David Foster Wallace. What do you think of that comparison?

LEVIN: It’s hugely flattering. He’s one of my favorite writers. But I don’t think it’s terribly accurate. Mostly that comparison is coming from the fact that I wrote a long book, and he wrote a long book, and there were schools in those books, or something, and a lot of characters. On a sentence level, I don’t resemble him all that much. I think he was much smarter than I am. Narratively, we have different goals. David’s agenda is really fractured, and it jumps around a timeline readily. And my book, The Instructions, is really straightforward—four days in a row with some flashback stuff interspersed but in a queer, kind of guided way. Like I said, though, it’s flattering.

STEIN: It’s interesting that you mentioned that you and Wallace have totally separate sentence structures. In a lot of your writing, you create your own particular vocabulary and idiosyncratic language, as Wallace also tended to do.

LEVIN: In terms of different sentence styles, there are long sentence writers and short sentence writers. I tend to writer longer sentences; Wallace writes longer sentences, so does Roth, so does Salinger. Even Saunders has his long sentence moments—they just don’t seem that way, because clause-to-clause they’re so sneaky. In terms of using an incredible vocabulary, I guess I do do that a little bit in Hot Pink, but it’s more of an Instructions thing. It came about because at first I was thinking, “I don’t want to swear a lot.” As a little kid, I swore a lot, and when I hear little kids in my head, they’re swearing. That could be bad to read on the page. So, I was like, how do I replace these swears and be character indicating and create tension at the same time?

STEIN: Tell me about the humor and slapstick comedy in your writing—what comedians influence you?

LEVIN: Particularly with The Instructions, I was thinking a lot about Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers. Who doesn’t like comedians? Right now, I think Louis CK is amazing. I love comedians. Not all comedians—there’s crappy comedy like there’s crappy literature. But I think the great comedians are doing something really amazing.

STEIN: What’s your writing process like on a daily basis?

LEVIN: Pretty boring. I wake up early and make some tea or coffee, depending on what year it is. Smoke a lot of cigarettes, drink my tea or coffee, and write until my back hurts. Then I go take a walk, and then the rest of the day starts.

STEIN: Is this a tea or a coffee year?

LEVIN: This is both, actually. I think I’ve reached my compromise, which is tea in the morning and coffee in the afternoon. I’ve worked it all out.

HOT PINK IS OUT NOW.