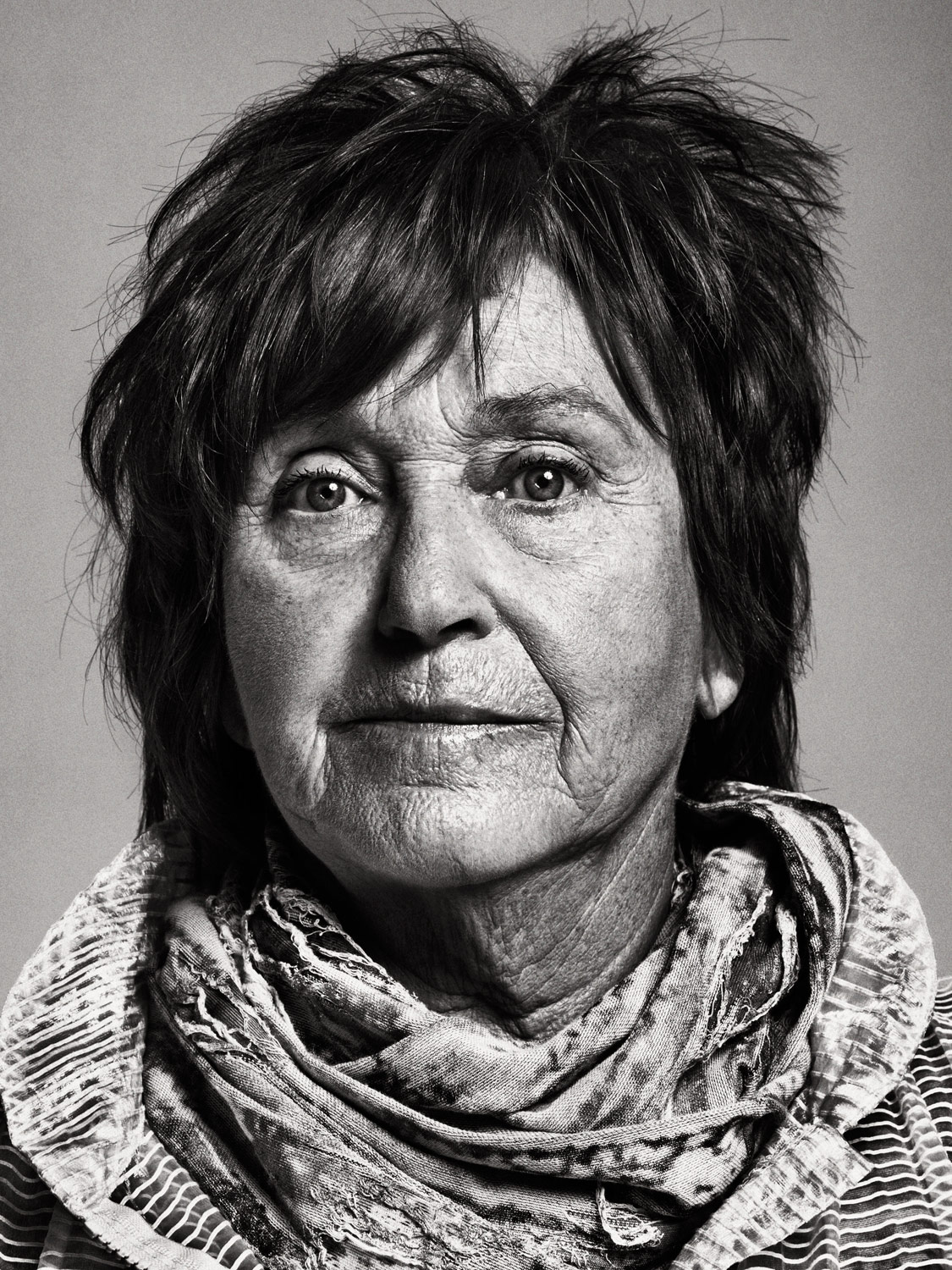

Valie Export

this was the strength of the female body: to be able to express directly and without mediation.Valie Export

When she changed her name in 1967 to VALIE EXPORT, the Austrian artist Waltraud Höllinger (née Lehner) renounced the names of her father and her former husband—tokens of patriarchal ownership—and transformed herself into a brand identity. Almost immediately after this break, EXPORT, then 27, began to develop a body of the most important experimental feminist art of the postwar period, exploring the nexus of relationships among politics, experience, and personal identity. Like her Actionist confreres who challenged the norms of an anxious and repressive Viennese society, EXPORT pushed her radicalism towards forms that were confrontational, aggressive, and, at times, shocking. In her iconic TOUCH CINEMA from 1968—“the first genuine women’s film,” as she put it—EXPORT stood on a street with a Styrofoam case over her bare chest inviting passersby to part the curtains with their bare hands and feel its contents: her breasts. The following year, Genital Panic took her into a Munich movie theater wearing a pair of pants with the crotch cut out. There, she presented the surprised audience not with the image of the female body they were expecting on screen but with real live flesh. Then, in Facing a Family (1971), EXPORT broadcast on Austrian national television five minutes of a family staring quietly into their TV set, mirroring the viewing audience at home by filming a family looking back at them.

While the feminist and sociological dimensions of such works are plain to see, EXPORT insists that they are also about exploring the frameworks of the media themselves. Staging an experience of film that was tactile rather than optical, TOUCH CINEMA set up a direct analogy between the movie screen and human skin, challenging the moviegoer to establish a relationship with the body based on proximity and intimacy rather than visual mastery and voyeurism. This interaction between the human figure and its media image motivates much of EXPORT’s art. In some works, like TOUCH CINEMA, the media are humanized and given a bodily aspect, while in others, conversely, the body is forced to conform to alien formats. Her important series of photographs Body Configurations from the 1970s showed the artist contorting herself to accommodate a variety of environments, from urban architecture to natural landscape. She was becoming part of the architecture.

Since these influential works, EXPORT has continued over the past several decades to develop means of artistic expression that are both exhilaratingly direct and utterly mediated. Now, as she moves increasingly into the new aesthetic territories opened by digital media, she is once again, at age 72, influencing a new generation of artists interested in the connections among live performance, body art, and contemporary technology. This May, I sat down with EXPORT, who was in New York briefly to meet with curators at the Museum of Modern Art, which recently acquired a substantial body of her work. This interview was conducted in German over coffee.

DEVIN FORE: I recently read that you no longer do live performances, but are instead focusing on video, photography, and media installations. I was surprised because so much of your early work was about the body as a presence and a force, and live performance is such a powerful theater for that.

VALIE EXPORT: It’s not true that I don’t do performance art anymore. At the 2007 Venice Biennale, I did a 12-minute performance in the Arsenale that showed the vocal folds of my throat while I was speaking. It was called the voice as performance, act and body. After a camera was inserted through my nose, the image was shown on large monitors so that you could see my vocal folds in the process of speaking. It was my own text that I read in German, a poetic text about the origin of language. “What is the anatomy of language?” I asked. My answer was just as much a body performance as any of my earlier works. Whenever we think of the body as a vessel for artistic ideas, we somehow always focus on the surface of the body. But the truth is that there is no surface of the body independent of its interior. It’s obvious that the outside of the body is always connected to the inside, to thought processes and to an internal anatomy.

FORE: An important claim of your early work was that the female body speaks the language of objects. For most of written history, men have been the authors of texts about the bodies of women.

EXPORT: In the 1960s, our attempts to cultivate a direct and uncontrolled language in art were based upon the idea that the dominant language was a form of manipulation. The plan was to circumvent these forms of social control and to develop other forms of language outside of the system dominated by men. This was the strength of the female body: to be able to express directly and without mediation. Much of the art of the time, from body art to video and direct performance, was concerned with similar issues. And then there was media art, which made it possible to express things directly, without having to rely on the written word, which as you said, was manipulated by men.

FORE: Your experimental film Syntagma [1983], parsed up and reframed the body through a variety of cinematic montage techniques—doubling the body through overlays, for example. After that film, it’s difficult to see the female body as something other than a constructed code. It’s hard to see it as something natural.

EXPORT: The female body has always been a construction. Even feminist art of the 1970s fashioned a body in accordance with its own ideas, and in this regard it was a form of manipulation too. Subsequently, we’ve had to engage with a lot of things that we used to disavow as manipulation. We can’t just dismiss everything as manipulations anymore, since the alternatives are constructions, too. From our perspective, from this corner of the planet, we have to admit that it’s all constructed. There is absolutely no nature. Nature is one of the biggest constructions.

FORE: So is time. For a period, your work was dedicated to analyzing time. In the 1970s, you were taking time apart and showing how it operates. In your installation Time and Countertime [1973], for example, you juxtaposed a bowl of melting ice with a video monitor showing another bowl in the same process of melting, only in reverse. Un-melting, so to speak. Today time is the dimension that everyone is preoccupied with—like the tremendous popularity of Christian Marclay’s recent video The Clock. But you seemed to be one of the first artists to recognize that globalization isn’t just about land or space. It also involves manipulating time and controlling it.

EXPORT: My interest in time emerged out of an engagement with the media that I was working with. Film and performance are temporal media. They rely on time. When I’m carrying out a performance, it matters, for example, how long I hold one particular gesture or posture. Seriality is very important too. Performance can be used to dilate time or to repeat time. And video, in turn, has its own time.

FORE: In a number of your works, it seems that the performer is trying to synchronize herself with the flow of time, but this attempt never quite succeeds, or if it does, it succeeds only for an instant. In Address Redress [1968], for example, a live actor delivers a speech in front of a pre-recorded audience that applauds and cheers her on at various intervals. Or in Ping Pong [1968], another actor, who stands opposite a film showing a dot slowly appearing and receding, tries to hit the dot with a ping-pong paddle. The timing in these films is awkward and doesn’t sync up.

I wanted to find out what happened when you leave behind this voyeuristic mode and confront people with reality.Valie Export

EXPORT: Well, time in video is totally different from time in celluloid. With video, I can show you something that’s unfolding in the present. I can show you what’s happening at the intersection down the street right now. It’s live. Film, on the other hand, always has to be developed beforehand, so there’s a structural delay. But the celluloid image also has a strict permanence. With video, I no longer see the image since it has already disappeared. The image dissolves and is immediately replaced by another before your eyes. And digital recording presents still other issues that are distinct from film and video at a very basic technical level. Its images are made out of a different material. I’ve always been interested in the material basis of artworks and images, whether that’s canvas or a film screen. Painting is an interesting case, but painting was for me too historical, too conventional. Of course, all forms of art are conventional, but in the ’60s we began to turn to other media, other materials for conveying images. I wanted to interact with the canvas and to agitate the canvas. Using skin or paper as screens, I explored how the quality of the image changed in different media and across different materials. My work became more and more ephemeral as I moved increasingly toward images that exist in the mind. These were images without any material basis. Some of them don’t even exist in documentation when I’m finished. And so ultimately I arrived at a philosophical question: How do I express a fugitive image that exists only in the mind?

FORE: It sounds like you’re talking about dreams. In the 1970s, you conducted a series of experiments in which you went to bed wearing various costumes and physical restraints in order to see how they would affect your sleep and influence your dreams. What did you see?

EXPORT: There’s very little documentation of that work. I tried out all kinds of things. I slept wearing ice skates and then hiking boots, for example, and tried moving around in them to see if they would dictate my dreams. In the end, they didn’t exactly dictate my dreams in their entirety, but they certainly did influence them. Sometimes I had nightmares in which I couldn’t move. Other times I seemed to know in my sleep that it was a performance. These performances were never about communicating anything. What I wanted was to undergo an experience, to learn something about myself and the possibilities available to me. I wanted to acquire knowledge.

FORE: The idea of art as a personal experiment strikes me as something very particular to your work. This was something that really surprised me about Marina Abramovic’s 2005 reenactment of your famous 1969 action Genital Panic, in which you walked through a Munich movie theater wearing a pair of pants with the crotch cut out. In your case, this work was a path to knowledge through an experiment. But Abramovic reenacted the work in a completely different circumstance—a series of performances at the Guggenheim in which she reenacted well-known pieces by other artists. For you it was an action, but for her it was a performance. And I wonder if, in this case, the distinction between the two versions of Genital Panic is not just aesthetic but ethical.

EXPORT: Perhaps, although I’m not sure I would draw such a stark contrast. Marina and I know each other, and she had my consent to do the piece. But what was really interesting for me was to see how it was received. I wore the action pants in a cinema. It never occurred to me to sit down in a gallery or a museum as if I were an artwork. That wasn’t my intention at all. Even the photo series [Action Pants: Genital Panic, 1969] in which I posed with a machine gun was shot only later and was not part of the original performance. These photographs became iconic, but that was just incidental. In fact, it was important to me that they not be elevated to the status of icons, because iconography always strives for conclusiveness. I wanted something multilayered, not something conclusive. The big difference between the two performances, then, is that I wore the action pants in a cinema, while Marina put herself on display in a museum. It’s a completely different context. As in many of her performances, she sits there for hours in a museum. She sits there, at a distance, but highly visible. It’s significant that the performance was in an American museum, too, since Americans tend to be prudes and don’t want to be confronted with these kinds of things. I think it was a successful work, but, yes, it was something entirely different from the original action. It was a different context and a different historical moment.

FORE: If, like many of your works, Genital Panic was a personal experiment, what did you learn from that particular experiment?

EXPORT: In 1969, I was invited to a film screening. I was wearing the action pants as a cinema action and I entered the movie theater saying, “Was Sie sonst auf der Leinwand sehen, sehen Sie hier in der Realität” [“Now you will see in reality what you normally see on the screen”]. It was a movie theater in Munich with a completely normal audience, so I walked through the seats, on display—nothing else, just on display. And some of the people in the audience got up, or at least all the ones in the back because they could get out the easiest. [laughs] The fact that this was reality was something that was unbearable to them. The action was designed to challenge the voyeurism of cinema. I was trying to develop a completely new, nonvoyeuristic approach to the female body as something other than a visual object. I wanted to find out what happened when you leave behind this voyeuristic mode and confront people with reality. But the fact of the matter is that they just walked away from it. That’s what was so interesting for me to discover: People don’t want to see reality. All of the time they just don’t want to see reality. It’s a pretty simple idea, really, this question of how we deal with reality. When something is constructed, when it’s projected onto a screen, it’s acceptable, but it’s different when it’s there in front of you in a public space.

FORE: And TOUCH CINEMA? That work tackles voyeurism as well.

EXPORT: There were numerous iterations of that piece, and each time I delivered a text about voyeurism in the cinema, about how the gaze works in the darkness of the movie theater, and about how it’s different on the street, out in the open. In public, everyone can see the faces of the visitors too, and how they visit it with their hands. My speeches were improvised, so I can’t recall them exactly, but they always had to do with the performance in the different cities.

FORE: How did people react? Were they aggressive?

EXPORT: I got very different responses. The first time I did it, which was at a film festival in Vienna, it caused something of a riot in the auditorium when a filmmaker yelled out, “Is this even film? Do we have to put up with this?” But the other performances of TOUCH CINEMA in Amsterdam, London, and other cities were quite lively and the audiences were excited in a very positive way. Only once, in Cologne, were the visitors to TOUCH CINEMA aggressive. The time we did the piece in Cologne, a performer named Erika Mies wore the box, and I spoke about cinema. We were both women, and people became very aggressive.

FORE: Did you feel a connection with the people who participated? What kind of experience did they have? It’s a very intimate thing to reach inside a box and fondle a woman’s breasts in public.

EXPORT: I can’t really say. Every time that I did TOUCH CINEMA, it was in public, and each visit to the cinema lasted 33 seconds, at which point it was broken off. Afterwards, the people seemed very satisfied. But what was particularly interesting about TOUCH CINEMA was the quality of the gaze, which was a completely different way of looking than the one you find in film. My gaze as well as the gazes of the visitors—who were both men and women—were incredibly powerful, extremely powerful and intense. There wasn’t any discussion afterwards, like there is conversation after a film, but I think it made quite an impression on the visitors.

FORE: TOUCH CINEMA explored the body as material for film in an entirely new way. By replacing the screen with skin, for example, you made cinema into much more than just a visual experience. It became a physical experience for the entire body. Media technologies create their own realities. People have often emphasized the fact that we experience a different reality through the camera, for example, than we do with our own eyes.

EXPORT: This is what was interesting about the work that I did five years ago in Venice, the voice as performance, act and body, in which you could see my vocal folds opening and closing—

FORE: Which was similar to the piece you made a couple of years earlier, The Power of Language [2002], where you showed close-up footage of the inside of a throat as it was speaking on six different monitors.

EXPORT: That was a similar project, but that time the vocal folds were a man’s.

FORE: There’s something very erotic about those images.

EXPORT: Incredibly erotic. Interestingly enough, people really thought they were looking at a vagina. It’s amazing what people project on to art. They experience themselves as being inside the body, and then, suddenly, language appears: Air goes in and the voice comes out. And it’s the same with the vagina––something goes in and something comes out. But a number of people leapt to conclusions and really thought it was an actual vagina on the monitors.

DEVIN FORE’S BOOK REALISM AFTER MODERNISM APPEARS THIS MONTH FROM MIT PRESS/OCTOBER BOOKS.