Thomas Ruff in Time and Space

THOMAS RUFF IN NEW YORK, MARCH 2016. PORTRAITS: FRANK SUN.

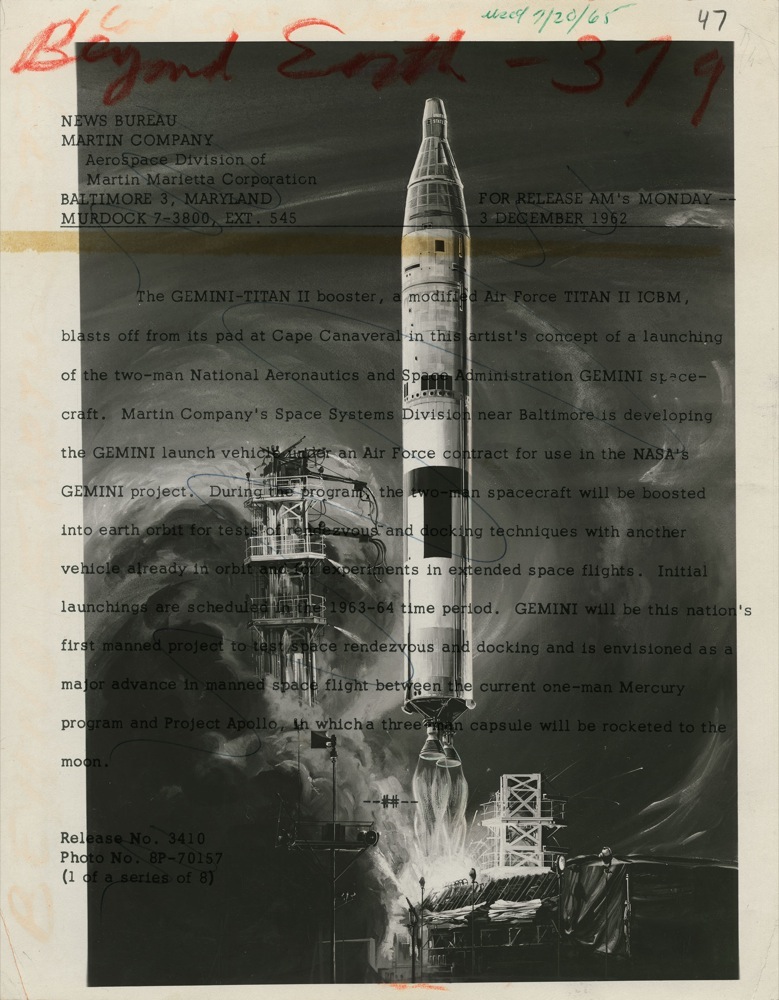

“When I was 19 and wanted to go to university, I had to decide to study astronomy in Heidelberg or art photography in Düsseldorf,” Thomas Ruff says when we meet in Chelsea. The artist chose photography, yet while walking through his solo show, “press++,” at David Zwirner, themes of space exploration resound. Large-scale photomontages depict American press photographs, culled largely from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, that Ruff digitally combined with their reverse, more logistical sides. The results include images like a rocket blasting off superimposed with typeface, and a black-and-white astronaut’s face interrupted by a red, sideways stamp. The size of Ruff’s final montages allow viewers to investigate original editors’ notes, pencil drawn alterations, and informational writing, instilling each press photograph with new meaning—or alternatively speaking, destroying each photo’s original intent.

Ruff began “press++” last summer, and one might see it as a combination of and response to previous series, including “Newspaper Photographs” (analog newspaper photos stripped of textual context) and “jpegs” (digitally disseminated images also devoid of context), as well as many others that have dealt with the overarching theme of the universe. For example, the 58-year-old’s “cassini” and “ma.r.s.” series are both based upon NASA imagery of Saturn, and copperplate engravings found in 19th-century electromagnetism books inspired his “zycles” series. The current space- and war-themed show at David Zwirner, however, serves merely as an introduction to “press++.”

“This is the premiere of the series,” Ruff says, as later this year he will have solo exhibitions debuting new works in Toronto at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and in Japan at the The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo and the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa. “I have some architecture, some from ballet, from the arts, Leonardo DaVinci…I have beautiful fashion photographs from the ’50s,” he continues. “I want to go through the whole newspaper, from the front, big international news to economics and culture.”

When Ruff decided to attend university for photography in 1977, he found himself studying with Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, alongside students including Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, and Andreas Gurksy (with whom he now shares a studio). Since the beginning, even when he was known for his portraiture and architectural series in the ’80s and early ’90s, Ruff consistently returns to question the construction and meaning of an image.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: How long have you been collecting these images, and where did you start finding them?

THOMAS RUFF: I’ve been collecting these photographs since I don’t know when, for a long time, for different reasons. You can find them on eBay and when we were browsing through the shops there were images that attracted me. One of them I got at my studio and I looked at the back and thought, “Wow, the back looks are as interesting or even more interesting than the front, maybe I should bring these two things together.” In the front you have the information of the image, and in the back you have things like that [writing]. Sometimes part of it is lost and you have informational stems and sometimes you have writing of the editor saying, “The cropping should be like this.” These are all historical images because these days they’re all digital. They don’t exist anymore.

MCDERMOTT: It’s interesting that you brought context into these images, because you purposefully stripped images of all context for “Newspaper Photographs” [1990-91]. Why did you decide to bring context back into the conversation?

RUFF: I think it is an anarchistic idea to have information on the front and the back. Normally if you add information to information, you have more information. In this case, I destroy information, I would say, because the image is disturbed by the writings. In a way, they become pure imagery. For me it’s really fun because it’s an idealistic approach to images, to just play around with information and see what’s happening.

MCDERMOTT: It reminds me a lot of the “Faking It: Maninpulated Photography before Photoshop” exhibit at the Met. The show had Dada photomontages and propagandist montages from the Soviet Union, among other manipulated images.

RUFF: Yes, and I’m really looking at some of those images. On some of these, the cropping is [drawn] on the front by the editor. These images are treated very badly by the newspaper people, and they have these writings, like the Egyptian hieroglyphs, things you don’t understand.

Also, I’ve worked with analog so the smallest part of the photograph was the grain, and then with digital, so it was the pixel. With some of these images, they have the AP Wire stamp, so they were not sent by post to the newspaper but transferred by wire. You have this new structure. It’s not digital, it’s not grain; the structure comes from transmission. Also, at that time, the reproduction technology was not so advanced, so the image needed the help of the editor—you can see they are painted to make them more pretty and defined. Some of them come from The Chicago Tribune and Baltimore Sun.

MCDERMOTT: Why did you choose to use only American newspapers?

RUFF: Because I did not find European ones. [laughs] And because I started with space, they were American press photographs.

MCDERMOTT: How did the series expand from space into war imagery?

RUFF: Actually, those images I bought for my private collection. I have some telescopes, I have some nice astronomy books, I have photographs, and destroyed photographs. If you go through catalogs on eBay, you find images, so these just attracted me and I bought them, even though at that time I didn’t know what to do with it. For example, this one [press++01.65], is not even a photograph; it’s an artist’s conception. It’s a reproduction of a drawing and on the back it has this yellowish glue—that “145” comes from the back.

MCDERMOTT: How many images did you start with? What was the process in determining what you wanted to scan and enlarge?

RUFF: The percentage is very small. I’m attracted to an image and then I look at the back. I make a quick and simple decision, I print it out, and I put it on the table. If there are 100 on a table, maybe five or six are then printed in this size.

MCDERMOTT: The scale surprised me when I walked in. I didn’t expect them to be quite this large.

RUFF: Yeah, actually when I had the idea of doing this work I was thinking of doing them in this size [gestures a one-foot-by-two-foot rectangle]. Then I decided this is the perfect size because if you go close, the pencil has this texture. If it was small you wouldn’t recognize it, but in this size you can see the pen and recognize the structure and see that [some of] the results are not photographic.

MCDERMOTT: Was the process entirely aesthetic, or did you ever contemplate the text?

RUFF: No, it’s only a matter of composition. It has nothing to do with “I want people to read the information that is there.” This work probably deals with my “Newspaper Photographs,” and I did another series called “Placarta” with this political montage where I also added type and image. But this is a readymade; it’s found, it already exists, all I do is add the back to the front. But the work definitely deals with how newspapers used photography at the time, how we look at photographs today, and how photography is treated and how people draw information into their brains.

MCDERMOTT: Given the current landscape of constantly changing media, how do you think the way images are treated has changed?

RUFF: Press information is serious information, but press information is also manipulated by people who want you to think that this and that happened. So it’s the old thing that you still cannot trust photography at all or you have to know who is distributing the photograph. In terms of cell phone photography, I think nobody cares about a photograph anymore because they’re taking so many pictures just for fun. I don’t know what people would think if they read the newspaper. Of course we still have the newspaper, and you have a photograph on the front cover, but even though they are playing around with cell phones and doing crazy things with them, do they still trust in this printed photograph? Or do they think, “This is just a fucking manipulated photograph.” Will they believe, “They can write whatever they want”? I don’t believe in that. [laughs]

Of course since photography is digital, it’s much easier to manipulate the photograph. It always depends on the intention of the person who’s giving this information and his or her responsibility of how far it goes. But if you look at photographers who say, “I hate digital photography,” they all use Photoshop, even if it’s to make the sky just a little more blue than it was. Manipulation is very discrete and because it’s so discrete nobody cares about it anymore. People accept manipulated photographs, I think.

MCDERMOTT: Then you also can look at citizen journalism and how certain news outlets just allow people at the scene to take a picture directly upload it. That introduces a whole new world of images.

RUFF: In that way, I’m very old fashioned. I still believe in the image and the pictorial quality of the image. It seems that I’m still busy with a truth in photography.

“PRESS++” WILL BE ON VIEW AT DAVID ZWIRNER’S 19TH STREET LOCATION IN MANHATTAN THROUGH APRIL 30, 2016.