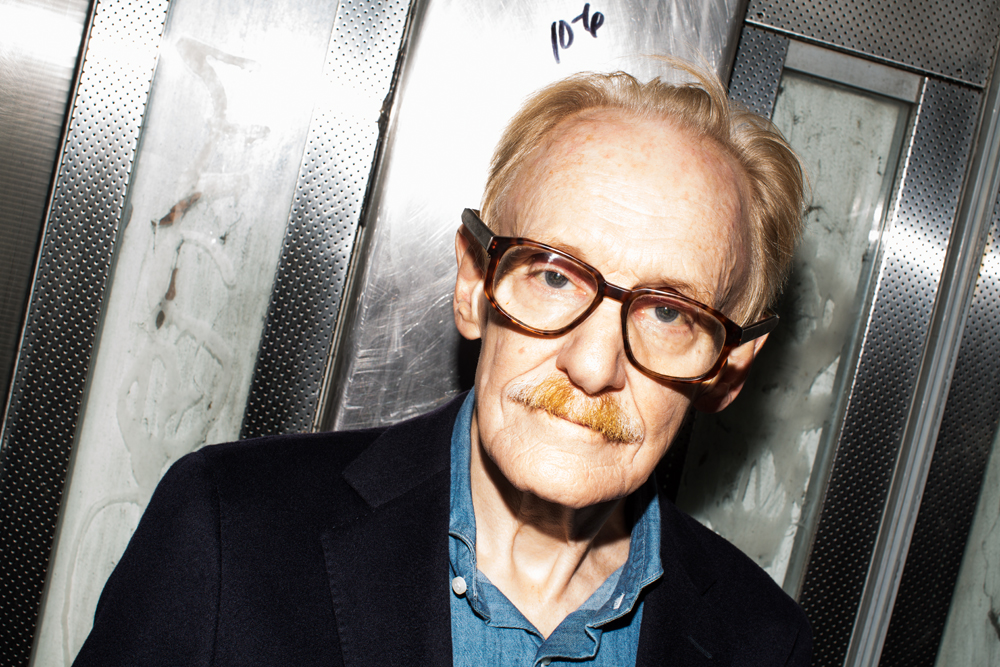

Peter Schjeldahl

I have two yardsticks as a critic: quality and significance. Is it good? Is it important? If it’s good and important, you’ve got a great artist. Peter Schjeldahl

ABOVE: WRITER AND CRITIC PETER SCHJELDAHL IN THE EAST VILLAGE, NEW YORK, OCTOBER 2014. ALL CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES: SCHJELDAHL’S OWN.

Anyone who complains that art writing is too dry or stuck up its own theoretical neuroses would do well to read Peter Schjeldahl’s articles in The New Yorker. Whether reviewing retrospectives, the reigning swingers of the art-world pendulum, or buzzy movements in retrograde, 72-year-old, East Village-based Schjeldahl proves time and again that looking is an active sport—and writing meaningfully about looking even more athletic. Schjeldahl is an art critic with an ear for poetry, and it’s little surprise that the North Dakota native came of age writing poetry himself in the 1960s under the influence of the New York School of painters and poets. He once wrote about Warhol, “Artists don’t change the world. But any big historic development makes room for a creative personality who, understanding it sooner and better than others, will come to symbolize it.” For five decades, Schjeldahl has been reporting on those symbolizers with wit, intelligence, a keen eye for all-splash-and-no-substance, and a passion that never gets in the way of his critical insights. And he can be critical. (He wrote in 2004 on minimalism: “Minimalism nailed the spiritual vacuum at the core of secular society, and the deep-down forswearing of judgment—open-mindedness like a hole in the head—that preserves democracy.” I include this quote because I admire the simile.) I sat down with Schjeldahl at an East Village café over breakfast to hear about art in the present—with no past and no future.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You’re also a poet. I think poetry is the best training there is for writing. It teaches an economy of words, but it also teaches the importance of sound in sentence structure.

PETER SCHJELDAHL: A poet is a master of the language. That’s what poetry’s for, bringing the language to peak efficiency. You know, I write by ear. If something sounds good, that doesn’t prove that it’s right. But if something sounds bad, then it’s wrong. I write very slowly and I rewrite a lot. On the first draft, there are usually a number of good sentences and a bunch of sick ones. I have to make them all well.

BOLLEN: You can’t write that slowly. You spent a good deal of your career doing art reviews for weeklies—for The Village Voice and 7 Days, not to mention for The New Yorker. That kind of schedule requires quick turn-around.

SCHJELDAHL: Yes, at The Voice and 7 Days, I was writing almost every week. Which I think was a nice rhythm. If I go two or three weeks without writing anything, it’s like a power plant: Once it cools down, you have to crank it up again.

BOLLEN: I was reading your columns from 7 Days, which were written in the short lifespan of that magazine—1988 to 1990. What struck me was that a lot of your reports and frustrations about the art world are just as valid today—especially in regard to the market taking over, that the influx of money is changing all of the relationships. In one piece entitled “Art & Money,” you have a line I particularly like: “The horror is not that art is overvalued but that, deep down, money is worthless.”

SCHJELDAHL: Well, that’s what happened in the ’80s. And it happened the first time around in the ’60s, with pop and Andy and minimalism. The audience and the economy of art exploded in the early ’60s. Before that it was very small. Even in the ’60s, all the galleries were sort of clustered on Madison Avenue and a few more on 57th Street, and that was it. The ’80s were definitely an explosion. In about ’87, there was the huge stock market crash, but the art world kept soaring. Then in ’89, there was a huge recession. It’s funny, we don’t remember recessions. Like, we don’t remember polio, or women don’t quite remember childbirth or else everyone would be an only child.

BOLLEN: So how did a poet who was born in North Dakota and grew up in Minnesota end up writing about art in New York?

SCHJELDAHL: I was always a poet, and actually I was the sports editor of my high school paper. I liked sports and I liked sports writing. I still like baseball. I went to college and dropped out, and by happenstance I walked into a job at a newspaper in Jersey City—The Jersey Journal—when I was 20. I spent a year in New York during which time I met poets. That was the time of the New York School. I met [Frank] O’Hara. He certainly became part of the theology of my style. “Oh Lana Turner we love you get up.” And I went to a poetry workshop taught by Kenneth Koch. After going back to college, I dropped out for good in 1964. Then I went to Paris for a year as a starving poet. I mean, I was really poor, hitchhiking around, and I got to fall in love with art. It dawned on me that I was in the wrong city. Guys in the Midwest at that time, we thought Paris was where it was at, but our information was 25 years out of date. [Bollen laughs] I remember going into a show in Paris at Sonnabend gallery of Andy Warhol flower paintings and thinking, “Wrong city!”

BOLLEN: So you hightailed it back.

SCHJELDAHL: I thought it was normal for poets to write art criticism. So I started doing that, and people liked what I did. For a while, I wrote for the Arts and Leisure section of the Sunday Times under a great editor, Seymour Peck, who was kind of my mentor and father figure.

BOLLEN: And I guess even in the prime of the New York School, poetry didn’t pay much.

SCHJELDAHL: I was doing art criticism to support myself as a poet. That continued into the late ’70s, when I started to feel like my art criticism was second rate. I wanted to see how good I could make it and let the poems take care of themselves.

BOLLEN: Why was it second rate? Did you feel like you were just painting in the lines?

SCHJELDAHL: At that time, there was a hangover in the art world from the traditional avant-garde, and journalism was a dirty word. But I also think for, like, 15 years, I was a nobody. I wasn’t taken seriously on the scene. You know, I hung out with artists, drank with artists, slept with artists, but I was “Peter the Poet.” One thing I say to youngsters in New York is, “When you arrive here and you’re a nobody, I know how painful that is, but this is your golden time.” Because if you’re a nobody, nobody is going to bother lying to you. The moment you’re somebody, you’ve heard the last truths in your whole life. Everybody’s going to spin you, as they should, because it’s a competitive town, right?

BOLLEN: That’s right.

SCHJELDAHL: Anyway, the poetry dried up. The art criticism ate the poetry. Meanwhile I had drifted out of the poetry world because it was sort of a horrible world. Rock music had pretty much obliterated it. Ever since Dylan, any kid who has the chops to be a poet is out in the garage with a guitar.

BOLLEN: Yeah, and the Language poets of the ’70s probably didn’t help matters.

SCHJELDAHL: No, but was a logical development in that they were sort of aping the minimalist avant-garde. But in art there was a commercial anchor. There is no commercial anchor in poetry. If you depart from convention in art, it gets noticed. If you depart from convention in poetry, nobody gives a shit. [laughs] Nobody knows the conventions.

BOLLEN: The majority of the leading public art critics today have their roots in the ’80s. You have a far larger historical window, starting in the ’60s. Have you found that the art world tends to be cyclical in that the same aesthetics or approaches keep coming around again?

SCHJELDAHL: No, it’s not cyclical at all. The present is always a mess. I came up with the romance of the abstract expressionists and the excitements of Andy. The ’70s were this sort of long depression, with a lot of woodshedding. It was the era of government grants and alternative everything, which I sort of hated. I wanted a little more public excitement. I got excited about the ’80s, with the return to painting, and maybe by the time of 7 Days, I was already disillusioned. The artists I was high on had mostly been sucked into the system and had been turned into production devices. Which is not a felony. It’s better than murder. [Bollen laughs] But I decided long ago that I’m not going to take the developments of the world personally. Nobody gets up in the morning with the intention of making me feel bad. If I feel bad, it’s on me.

BOLLEN: I said that the ’80s seemed a lot like this decade in terms of ultra-capitalism. But in certain ways, it is wildly different—one thing being the culture wars. The overriding group apathy of what is being made or expressed today almost makes me romanticize a time that Mapplethorpe could occasion protests or a political backlash against the National Endowment for the Arts. I simply can’t imagine anything made by artists today causing more than a squeak in the public discourse.

SCHJELDAHL: No, it’s still here. But it doesn’t register. If it doesn’t register on the cash register, it doesn’t exist. But, of course, it exists. This summer I wrote about Christopher Williams at the MoMA. He comes out of CalArts and the sort of heavy theory that I always hated. But he’s become so marginal that it’s sort of adorable. It was interesting to reevaluate it for myself and to realize that it came out at the same moment as Jeff Koons, and in fact, there was a kinship there. And I just wrote about Robert Gober. It’s also interesting that, in the ’80s, he was showing sinks and Koons was showing vacuum cleaners. They were both into hygiene.

BOLLEN: I guess you could say with Koons, he’s the artist we deserve.

SCHJELDAHL: I have two yardsticks as a critic: quality and significance. Is it good? Is it important? If it’s good and important, you’ve got a great artist. A lot of artists are very good, but not important. They don’t make a difference in the world. I have a lot of favorite artists that I don’t write about because I don’t want to presume on other people’s time. I’m a journalist.

BOLLEN: But can’t you influence who is deemed important? Isn’t one of your jobs to call out those who could become important?

SCHJELDAHL: No. That’s a young critic’s job. First of all, I don’t understand what it’s like to be young now. I sort of remember what it’s like to be young. But I’m very high on the food chain.

BOLLEN: Do you miss those hardscrabble days of writing about every new show you saw?

SCHJELDAHL: No way. I miss the energy that made it seem like no big deal.

BOLLEN: You’ve written about some artists multiple times through the years. I noticed you wrote a rather dismissive review of Christopher Wool when his work appeared at a Whitney Biennial in 1989. Obviously you’re going to change your mind over time. You wrote about his retrospective last year at the Guggenheim, and you did actually acknowledge your earlier problems with his work. It would be so easy to just forget your previous assessments.

SCHJELDAHL: I don’t write about the art, I write about my experience with art. So with an artist who’s been around, I carry a history. And I think just like anybody, I tend to react negatively to anything new. That’s human. We’re put together with Band-Aids and rubber cement, right? Then something comes along that violates that, and I think it’s a healthy human organism that will say, “No!” And if we can reject it and get past it, that’s great. But maybe it won’t go away, so eventually we incorporate it.

BOLLEN: You’ve been known to do battle with a few, I won’t say enemies, but antagonists in your time. One being the theory-laden academic-ese of the art world, particularly with the rise of the October critics like Rosalind Krauss.

SCHJELDAHL: That was done in order to achieve an academic hegemony. It was departmental politics. And part of the thing was to clear the decks of poets and connoisseurs and anyone who actually cared about art. To the extent that they ever noticed me, it was like a mosquito.

BOLLEN: Their work certainly shifted the conversation. And by shifting the reading of art, they shifted how it was produced and shown.

SCHJELDAHL: That did happen. But what wiped out what? At the end of the ’60s, I was very involved with a bunch of abstract painters, lyrical abstractionists. They were wonderful painters who had sort of come through [Clement] Greenberg but had gone back to a more lyrical approach. But when the recession hit, critically, between the grindstones of minimalism and pop, they were extirpated. But that happens. Don’t go to war if you rule out getting shot. It’s part of the deal. I have no patience for bitterness of any kind. Even to be involved with art is to inhabit such a level of privilege in life.

BOLLEN: You’ve said that the present time is always the best time. Is that because of the chaos of the present?

SCHJELDAHL: It’s because it’s the only moment ever. There is one time: the present. There’s no other time.

BOLLEN: So you feel you write best about the current moment?

SCHJELDAHL: Yes. I also breathe best in the moment. [laughs] But I mean it. People for whom the past and future exist are insane.

BOLLEN: But one of the difficult things about writing on the moment for so long—and even I’ve noticed this in my 18 years in New York—is that after a while you witness young artists making “new” work that is exactly like work that was made decades prior. The same thing over and over and over again. It starts to feel like eternal return.

SCHJELDAHL: Rachel Whiteread, when she was making casts of space under a chair, was doing exactly what Bruce Nauman had done in 1968. I said to Bruce, “Does that piss you off that she’s putting your idea into production?” He said, “No, she’s a good artist. I always knew there was more in that idea than I explored.” And there was. But overall, I guess I’m annoyed by the general level of amnesia. But all of the failures of that kind are self-punishing. They scuttle themselves.

BOLLEN: You’ve made some smart contributions to classifying recent phenomena in the art world. You coined Festivalism in 1999.

SCHJELDAHL: Festivalism is the one capitalized noun that I’ve generated.

BOLLEN: Well, just this past summer, you coined Stunt art. Do you ever feel like art gets carried off in the outrages of the young? Part of the fun in art is how everyone’s trying to upset the established system—whatever system is currently in play. But sometimes it gets a little juvenile, a playground of ugly games.

SCHJELDAHL: Well, that’s true not only of every youth movement, but every youth. What do you do when you’re a teenager? You come along with all the good glow and energy and excitement into the world, and you quickly realize that nobody has been waiting for you. [Bollen laughs] That either brings you back into working at the gas station or you start plotting your revenge. And artists are extreme about it. All artists are unhappy people. You wouldn’t be an artist if you were happy, because that would mean that the world is full of [looks at table] Tabasco sauce and galaxies. Why would you want to add something?

BOLLEN: What about critics? Are they unhappy people?

SCHJELDAHL: Oh, very unhappy.

BOLLEN: So in the simplest terms, how do you look at a work and gauge if it’s good or bad? Or at least if it’s successful or not?

SCHJELDAHL: If I don’t like it and have to write about it, I have a test, which is that I ask myself, “What would I like about this work if I liked it?”

BOLLEN: Can you always find something? Is it like trying to find something good in a grandchild you aren’t that crazy about?

SCHJELDAHL: Generally, I can. It’s like, “What is the mind-set that’s not mine?” And if that fails, I ask myself, “What must the people who like this be like?” Then I’m into sociology. It’s like with Damien Hirst. His art is not good. Goodness has nothing to do with it. But it becomes a phenomenon. Koons becomes a phenomenon, but walking through it, I say, “Wait a minute, Koons is good, very good.” It’s affecting us. I mean, there’s going to be a period where Koons will be reviled again. The culture will shift away from him. But then he’ll come back and be reevaluated. That’s my prediction. Don’t sue me if it doesn’t happen.

BOLLEN: I think you hit the nail on the head earlier on Koons when you brought up the sanitary or hygienic quality of the work—that obsessive perfectionism. To me that’s more interesting than the kitsch-, pop-, fine-art trajectory.

SCHJELDAHL: The guy’s crazy, but, boy, does he have a touch. And he’s incredibly active. He’s sort of a visionary Amway salesman. His view of society would be cynical in anyone else.

BOLLEN: You’ve done few profiles at your time at The New Yorker. I read a New Yorker profile you did on John Currin, where you two went and looked at the Old Masters at the Met. Does it help for you to talk directly to artists?

SCHJELDAHL: I rarely talk to the artist. And everything in their biographies is already so well documented anyway. I can’t write about people, which is why I write about inanimate objects. I cannot relate. I’m a narcissist. [laughs] I deal with everybody the way they deal with me.

BOLLEN: I know from reading you that you spend time wandering the museums—the Met, MoMA, the Frick …

SCHJELDAHL: For the last seven years of the New Yorker Festival, I’ve conducted a tour of the Frick. The Frick has been a plank for me ever since the ’60s, when I didn’t know anything. It was free, I went in and wandered around, and I fell in love with one thing after another. It was my public university. I’ve spent a lot of time with the paintings before I even knew anything but the artist’s name.

BOLLEN: Today, and I’m just as guilty, we all go right for the wall text before we have a real look at a painting. We want to be over-informed before we even start. No one wants to be caught staring at a vertical stripe with their pants down.

SCHJELDAHL: Yeah, and often the texts are horrible. But I figure that you can’t not read them. I think of it as primordial. You know, the writing on the wall. Beware of the saber-toothed tiger. You’re going to read it.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS THE EDITOR AT LARGE OF INTERVIEW MAGAZINE. HE IS ALSO A FICTION WRITER. HIS SECOND NOVEL, ORIENT, WILL BE RELEASED BY HARPER IN APRIL 2015.