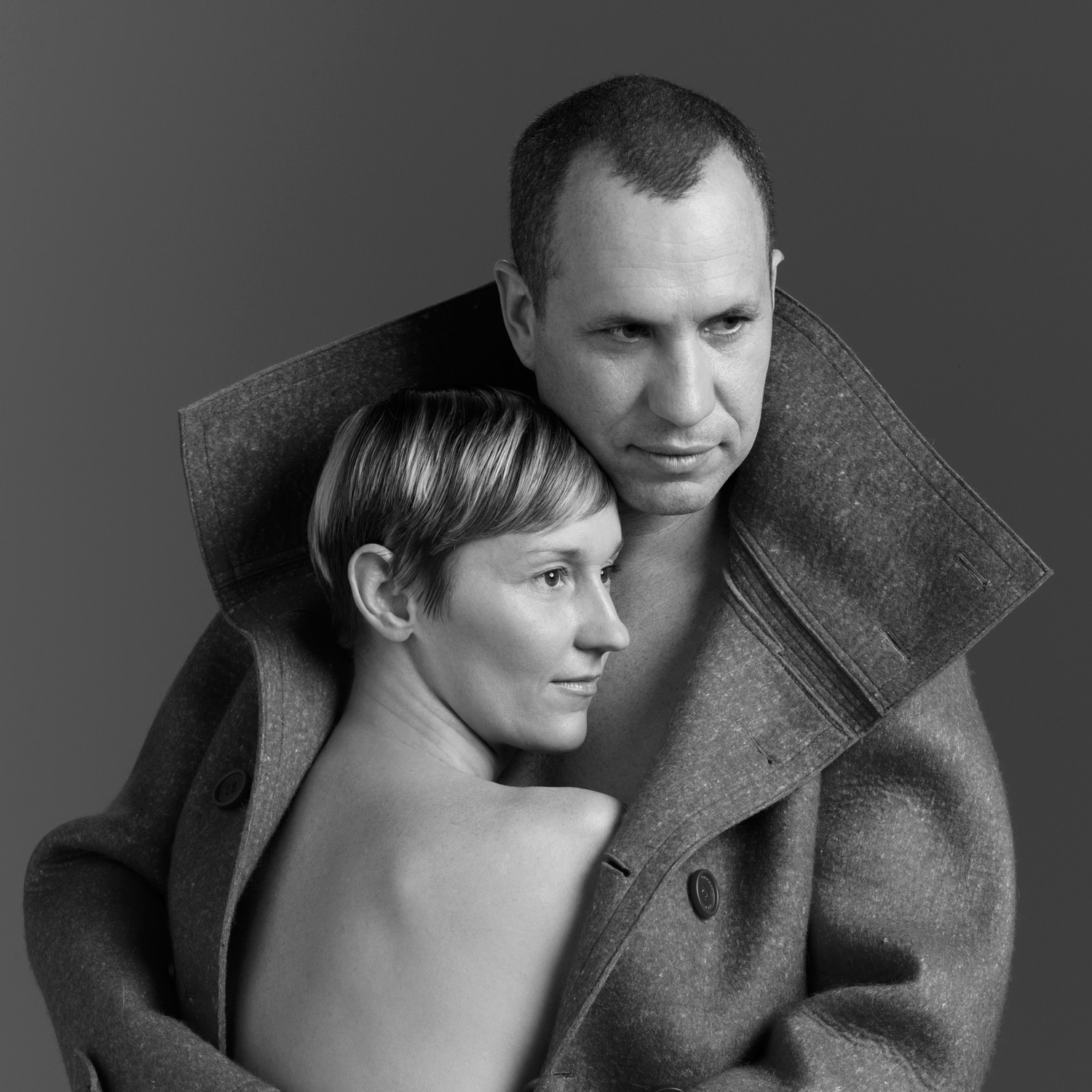

Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla

before you know whether you like it or not, there’s a physical response. it’s like an organism; it has its own teeth and it goes for you.Guillermo Calzadilla

Jennifer Allora, 37, and Guillermo Calzadilla, 40, met more than a decade ago as artstudents abroad in Florence, Italy, and have been working together ever since—not necessarily always seeing eye to eye, but thinking as one. Though based in Puerto Rico, they have exhibited their provocative sculpture, videos, installations, and performance works mostly in Europe. This rather disproportionate overseas interest may explain why many in the New York City art world expressed surprise when they were chosen to represent the United States at the 2011 Venice Biennale, when it opens on June 4.

Sound is central to Allora & Calzadilla’s work, as anyone passing through the atrium of New York’s Museum of Modern Art discovered late last year. A pianist enacting the artists’ Stop, Repair, Prepare rolled a grand piano through the space while playing Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” upside down and backwards, from a hole cut into the instrument’s soundboard. (Their work has also employed opera singers, brass bands, turtles, and a camel.) Political references abound in all of it, as does irony. Their show for the American pavilion in Venice, where they will install an army tank, a group of world-class athletes, including two Olympic medalists, and a working ATM machine inside a pipe organ—a Biennale first—ought to give people plenty to think—and laugh—about, and possibly scare them silly, too. I caught up with them and their 18-month-old daughter, Isa, in NYC, where we discussed war, music, and what it is to be an American artist.

LINDA YABLONSKY: How long have you been together?

GUILLERMO CALZADILLA: Fifteen—

JENNIFER ALLORA: Sixteen years.

YABLONSKY: We’ve only just begun and you’re already disagreeing?

ALLORA: That’s half of our relationship—fighting.

YABLONSKY: You work together all the time, and now you’re raising a child. How do you manage?

ALLORA: All of us is all one thing, all part of our dysfunctionality. Everything becomes a personal problem or becomes part of our work problem. There’s just no separation.

YABLONSKY: Guillermo was born in Cuba and now you live in Puerto Rico?

ALLORA: We’ve lived in Europe more.

YABLONSKY: So weren’t you surprised by your selection to represent the U.S. at this year’s Venice Biennale?

ALLORA: We were shocked.

CALZADILLA: But the U.S. pavilion became a great adhesive to put ideas together that were not fully developed.

ALLORA: And now we have to make all this stuff! But we’re happy about it, for sure.

YABLONSKY: The American pavilion is not the most graceful building.

ALLORA: Yeah. It’s very depressing to be next to the Scandinavian pavilion, which is so gorgeous.

YABLONSKY: It’s like a bunker. Isn’t one of your artworks a bunker?

ALLORA: Clamor [2006], yeah. A hybrid bunker with a five-piece brass band inside, each playing a different type of music associated with war—Ottoman Janissary marches, Sousa marches, and the music of

AC/DC, which was used in the first Iraq war.

CALZADILLA: Where you might see a rifle or canon coming out, here it was a trombone—

ALLORA: Or a flute player. And it was really, really loud.

YABLONSKY: I remember your 2004 video Returning a Sound where there was a trumpet attached to the muffler of a moped that a man was driving around Vieques, Puerto Rico, which was a weapons-testing ground until 2003.

Clamor, 2006

CALZADILLA: It came out of our research on the history of musical instruments and the battlefield.

ALLORA: Instruments like the cymbal and the bass drum were introduced to western classical music as a result of—

CALZADILLA: Wars.

YABLONSKY: A lot of your work seems tied to war.

ALLORA: Making work in Vieques started us thinking about militarism, but there’s a big musical culture in Puerto Rico, too. For a while we pursued works that linked those two things.

CALZADILLA: And we deal with it by using sound.

ALLORA: Which creates this effect—something that makes you feel something before you’ve attached any cognitive or emotional . . .

CALZADILLA: Meaning. Before you know whether you like it or not, there’s a physical response. It’s like an organism; it has its own teeth and it goes for you. It can be nice to you as well.

ALLORA: The first time we did Clamor was more an attack. So was the piano [Stop, Repair, Prepare], because it was on wheels and pushed people around. I don’t know why, but some of the work we make comes across as aggressive.

CALZADILLA: I don’t think it’s aggressive!

ALLORA: It’s interesting how one material behaves against another. We made one work called Sediments, Sentiments [2007] to make a relationship between geology and politics, two things that have nothing to do with each other.

CALZADILLA: Unexpected juxtaposition is something we love. This had opera singers lying down inside a gigantic sculpture that looked like a ruin, and they were singing fragments of political speeches.

YABLONSKY: In Venice, you’re parking a military tank in front of the U.S. pavilion?

CALZADILLA: It’s an upside-down tank that has a treadmill attached to one of its tracks, so when you turn on the treadmill, the tracks move.

ALLORA: It’s massive. And ugly. And obnoxious.

CALZADILLA: It’s called Track and Field.

ALLORA: Dan O’Brien, the 1996 Olympic decathlon champion, is going to be running on the treadmill.

CALZADILLA: It makes the relation between the military and sport explicit. And because the tracks don’t touch the ground, they produce a sound you haven’t heard before. And you’ve never seen a treadmill on a tank before. So the meaning becomes larger than the sum of its parts, mainly through defamiliarization.

YABLONSKY: I’m amazed you got this idea past the U.S. State Department.

ALLORA: That’s why we were so shocked when we got it. We thought everything we proposed was over the top.

YABLONSKY: You’re also using Olympic gymnasts?

ALLORA: David Durante, a national all-around champion, and Chellsie Memmel, an Olympic silver medalist. We have two objects: a replica of an American Airlines business class seat and one from Delta, the newest, reclinable bed seats. But what they suggested to us was something closer to a balance beam and a pommel horse. So the men are going to do their routines on the American seat, and the women on the Delta seat.

CALZADILLA: We became obsessed with the forms and what they represent.

ALLORA: They’re symbols of nationalism. A lot of power and effort go into the design—and nations support these companies. American Airlines can never go bankrupt. It would mean something to our national identity. We also think the seats are curious as objects, and the idea that you’re traveling at 600 miles per hour but you’re supposed to be lying very still. And gymnasts are people whose skill is to perform gravity-defying movements.

YABLONSKY: I heard you were going to put a cash machine in there too.

CALZADILLA: It’s an ATM, but the keys replace those on a church pipe organ—this is the soundtrack for the pavilion.

ALLORA: So people who aren’t interested in art can just get cash.

Linda Yablonsky is a novelist, art critic, and frequent contributor to Artnet, The Art Newspaper, and the Scene & Herd column on Artforum.com.

Click here to see past exhibitions.